There’s a plague of fake news surrounding the Covid-19 pandemic which occasionally has deadly consequences. Banning fake news, however, is hardly a solution, since governments, too, are prone to providing bad information.

The best advice in a crisis is to remain calm, rational and sceptical. This is not, however, how public opinion works. Amongst the public, the most hysterical, gullible and conspiracist voices often rise to the top. With the network effect of social media, memes spread, much like a virus, from person to person, and successful memes gain popularity at an exponential pace.

I use the term memes here in its original sense, not as a picture with a funny caption, but as ‘an idea, behaviour, style, or usage that spreads from person to person within a culture’.

‘Memes (discrete units of knowledge, gossip, jokes and so on) are to culture what genes are to life,’ wrote Richard Dawkins in his best-selling book, The Selfish Gene. ‘Just as biological evolution is driven by the survival of the fittest genes in the gene pool, cultural evolution may be driven by the most successful memes.’

The public is subjected, daily, to an avalanche of information, misinformation and disinformation. In the context of Covid-19, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, the director-general of the World Health Organisation (WHO), warned of the need to fight not only a pandemic, but also an ‘infodemic’, as he termed the deluge of false information.

As early as 15 February, he called upon governments and media organisations to cooperate in stifling fake news, and reported that the organisation was already working with technology companies including Facebook, Google, Pinterest, Tencent, Twitter, TikTok, and YouTube to ‘counter the spread of rumours and misinformation’.

Collective sense-making

For the average person, in a situation where there are significant unknowns and changing circumstances, fact and myth can be hard to tell apart. Many make choices and decisions based on emotion, not evidence, and, in turn, make demands of their political leaders to do the same.

The epidemic of economic lockdowns implemented in response to the Covid-19 outbreak is as much a consequence of the authoritarian instincts of governments and inter-governmental organisations such as the WHO, as it is of the demands of a populace alarmed – and hence clamorous to be led to safety – by an endless series of hobgoblins, many of them imaginary (to misquote the great H.L. Mencken.)

According to crisis informatics researcher Kate Starbird, when information is uncertain and anxiety is high, people’s natural response is to try to resolve that uncertainty and anxiety through a process of ‘collective sense-making’. In today’s world of overabundant information, the challenge is to decide which information to trust, and which to distrust. This challenge becomes harder when official sources become distrusted.

‘When elected leaders share dubious information and contradict their own agencies and scientists,’ Starbird writes, ‘this lowers our trust in official response agencies and reduces our ability to identify the best information at the time. These also increase uncertainty and anxiety and potentially cause people to take actions that may be harmful to themselves or others.’

Conspiracy theories

Many examples of fake news have their origin in a deep distrust of government and sinister business interests. While distrust in the authorities is often justified, a good rule of thumb in the absence of evidence is to apply both Occam’s and Hanlon’s Razors. The first says that the simplest explanation is most likely the right one, and the second says never to attribute to malice what can adequately be explained by incompetence.

Failure to do so easily leads to the development of elaborate conspiracy theories. That some conspiracies have turned out to be real – witness the systematic government lies exposed in the Pentagon Papers, or the CIA’s MK Ultra programme – only strengthens the belief of their proponents.

So we have seen absurd theories such as that fifth-generation (5G) mobile networks, designed for higher throughput at shorter range, ideal for the multitude of connected devices entering the market under the ‘Internet of Things’ banner, causes Covid-19.

It is premised on the myth that electro-magnetic radiation can cause all sorts of vague and general symptoms, which, if they exist at all, are more likely to be caused by stress, poor sleeping habits, lack of exercise and a poor diet.

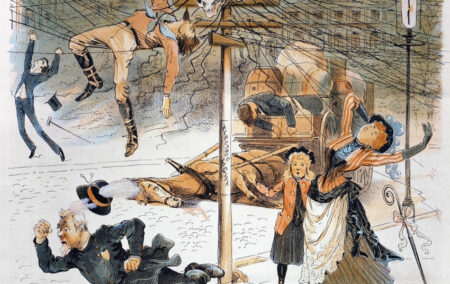

We heard this when 4G came around, before that with 3G, and before that with mobile telephony in general. Before that, television and radio signals were believed to cause all manner of harm. The myth is literally as old as electricity, as this cartoon from 1889 demonstrates:

Many articles in the popular press have debunked the preposterous notion that 5G causes Covid-19, or is harmful at all.

Then there’s the theory that Bill Gates planned all this so he can vaccinate people and, well, kill them. Conspiracy theorists, mostly from within the anti-vaxxer community, call this his ‘depopulation agenda’.

This theory also long predates Covid-19. Gates, through the foundation run by him and his wife, has long promoted vaccination and childhood health. It wasn’t always so. He is a Malthusian, and believes that population growth places an unsustainable strain on the world’s limited resources. At first, he believed that vaccinating children in poor countries would be counterproductive if you wanted to limit population growth. As he learnt more about how the world beyond computers works, he realised that poor people have lots of children because they expect some of them to die. Therefore, improving childhood health and development through measures such as vaccination programmes, but also nutrition, education and other interventions, would lead people to choose to have fewer children, and thereby reduce population growth, as has happened in the developed world. Conspiracists seized upon phrases like “reduce population growth” and “reduce fertility”, and, not understanding these terms, came to believe that Gates-sponsored vaccinations were sterilising and/or killing people. It’s all nonsense.

But it will lead people to refuse vaccinations against Covid-19, if and when they become available, which unlike the vaccinations themselves will actually kill people.

Banning fake news

Some governments, including South Africa’s ruling junta, were quick to pass regulations that criminalise spreading fake news with the intention to deceive. The first charge under this regulation was laid by Siviwe Gwarube, a Member of Parliament (MP) for the nominally liberal Democratic Alliance (DA). It involved an unfortunate fellow with a cotton swab up his nose, who urged people to refuse coronavirus tests because they were contaminated by coronavirus. He was released with a warning, but could have faced jail time. DA MP Phumzile van Damme called the arrest ‘a victory in the fight against disinformation’.

Lost in the widespread public condemnation of this chap was the fact that coronavirus test kits have, in fact, been contaminated with coronavirus, according to the New York Times. These tests, produced by the Centers for Disease Control in the United States, were exported to other countries, including the UK. That may not prove that test kits used in South Africa were contaminated, but the guy wasn’t all that far from the truth.

Instead of demonstrating the provenance, safety and effectiveness of South Africa’s test kits, the government simply dismissed public fears as ‘fake news’, and silenced those who spread it. This is one way censorship protects those in power from public scrutiny.

Fake news isn’t just spread by paranoiacs on social media.

The Mirror, a UK tabloid, ran with the story that a British man, who contracted Covid-19 in Wuhan, China, ‘beat flu with a glass of hot whisky’.

The news of alcohol’s supposed curative properties spread around the world, eventually making it to Iran, where alcohol is banned. To ward off Covid-19, people procured alcohol from bootleggers. As a result, more than 700 people have died, and many more have been blinded or become ill after consuming methanol, the wood alcohol that distils off a batch of liquor before it reaches the boiling point of ethanol. Unlike ethanol, which is safe to drink in moderate quantities, methanol is toxic.

With alcohol now being banned in South Africa, too, locals who turn to the black market for their fix face the same risk, whether or not they believe alcohol will cure or prevent Covid-19.

The venerable Guardian ran with a story, sourced from a tweet by the French health minister Olivier Véran, that anti-inflammatory drugs like cortisone and ibuprofen could make Covid-19 worse. Véran instead recommended paracetamol as a first-line treatment for fever.

This was an entirely speculative but plausible hypothesis, but a hypothesis is all it was. It led many people who were taking anti-inflammatories for other reasons to stop taking them, however.

Two weeks later, a letter in the prestigious journal Science called it, ‘Misguided drug advice for Covid-19’.

A British Medical Journal paper on the question reported ‘no published evidence for or against the use of NSAIDs [non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs] in Covid-19 patients’, ‘some evidence that corticosteroids may be beneficial if utilised in the early acute phase of infection’, and ‘conflicting evidence from the World Health Organisation’. It advised that ‘caution should be exercised until further evidence emerges surrounding the use of NSAIDs and corticosteroids in Covid-19 patients’.

UK health authorities, more than a month after the Véran tweet reported in The Guardian, changed their advice, saying that ibuprofen can be used to treat Covid-19 patients. However, they did not publish the evidence on which this decision was based, so uncertainty remains.

Ironically, this could make both the claim ‘avoid ibuprofen’ and the claim ‘use ibuprofen’ susceptible to being declared ‘fake news’, and be criminally prosecutable in South Africa.

Fake news from the government

President Donald Trump played into the myth of an old but dangerous quack cure when he speculated during a press briefing that disinfectant, when ingested or injected, might cure Covid-19. People actually drank bleach in the wake of his astonishingly ignorant musings. Oh, for the record, drinking disinfectant is a bad idea, even as a suicide method.

When minister Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma announced the National Command Council’s about-turn on permitting the sale of cigarettes during level 4 of the government’s phased lifting of lockdown restrictions, she made a famous performance about why this was done.

She repeated the WHO’s advice that smokers are at greater risk of contracting Covid-19 because of the possibility of contact between a smoker’s hands and mouth.

She must know, thanks to her well-documented relationship with the country’s most famous illicit cigarette smuggler, that many South African smokers are still smoking. They’re just paying double the usual price for doing so, as recompense to cigarette retailers who would face criminal consequences if caught.

Instead of advising that smokers wash their hands regularly, and avoid sharing their ‘zol’, the ruling junta simply extended the ban on tobacco sales.

The Department of Health issued a poster declaring that ‘smoking can increase your chance of getting Covid-19’.

What neither they nor the ex-president’s ex-wife did was cite any scientific evidence that this actually occurs. A study of hospitalisations in China, where smoking is very prevalent, found a surprising lack of smokers among those ill with Covid-19, and hypothesised that nicotine may have a beneficial effect on Covid-19. This hypothesis was supported by the results of multiple studies, according to the authors,

Another study ‘does not support the argument that current smoking is a risk factor for hospitalization for COVID-19, and might even suggest a protective role’.

A paper in the New England Journal of Medicine finds that smokers, when they do get hospitalised, are more likely to require intensive care than non-smokers. This suggests that smokers are less likely to contract Covid-19, but when they do, it could go worse for them than for non-smokers.

The idea that smokers are much less likely to get Covid-19, but fare worse if they do, seems to be the general consensus at the moment. In France, front-line health workers and patients are being issued nicotine patches as an experimental prophylaxis against Covid-19.

This makes the claims by the Health Department and Dlamini-Zuma that smokers are at greater risk of contracting Covid-19 fake news. And it has consequences. Forcing smokers to quit raises anxiety and irritability, which, given the already extremely stressful lockdown, can only increase the risk of domestic violence. Nicotine withdrawal also causes a range of other physical, mental and emotional symptoms, according to psychiatrist Dr Mike West, interviewed in The Herald recently.

As for vaping, which is also banned supposedly on health grounds, there is absolutely no evidence linking the practice to Covid-19 infections. It ought to be encouraged, especially if the government hopes to convince people to quit smoking for reasons other than preventing Covid-19.

Even government information cannot be relied upon

The government’s projections of how the Covid-19 epidemic might progress can also not be trusted. The model on which it relies, and which has not been published for public scrutiny or peer review, has been described as ‘flawed and illogical and made wild assumptions’ by the former head of the National Institute for Communicable Diseases, Professor Shabhir Madhi.

One wonders if General Bheki Cele, the police minister, will arrest those responsible for all this government-sponsored fake news.

Unlikely, since the jackboot-in-chief is not averse to spreading some fake news himself. ‘This thing has the potential to wipe off the nation, wiping off humankind,’ he told the media on Friday.

No, General, it doesn’t. It does not have the potential to do that. What you’re doing is spreading fake news with the intention to deceive. This kind of talk whips up panic and hysteria. It spreads fear, which is exactly what the WHO’s Tedros cautioned against.

Legislating against fake news, while also gagging independent experts, leaves the government as the only source of information on Covid-19. This seems like a terrible idea if the government itself cannot be relied upon for factual information.

The current climate is tense enough as it is, with people losing jobs, people starving, families being separated, people losing loved ones, sheer boredom, loneliness and depression caused by the lockdown.

It is natural to hunger for more information, and more certainty. When we cannot even rely on the government for accurate information, we each need to take personal responsibility to make calm, measured and rational assessments of what is and isn’t true.

Do not be driven by fear or hysteria. An infodemic of wrong information can kill just as surely as the pandemic can, and we clearly cannot rely on the government to protect us against it.

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR

If you like what you have just read, subscribe to the Daily Friend