It’s January 2018. The country has just experienced an exciting and close-run political fight for the leadership of the ruling party with outsider Cyril Ramaphosa narrowly beating the favourite Dr Nkosazana Dlamini-Zulu to become, first, head of the African National Congress, and eventually president of the Republic of South Africa.

Much has been said and written about the (alleged) horse-trading that went on behind the scenes which (once again, allegedly) led to power-broker David Mabuza switching allegiance from Dr Zuma to CR at the last moment, pushing the former trade union boss over the line to win the ANC-leadership race by the proverbial nose.

Most South Africans, and indeed the rest of the world, reckoned this was a win for the ‘good side’ within the ruling party, as NDZ was somehow seen as a proxy for her former husband, ex-president Jacob Zuma, who – had she won – would have been back in power, directing things from behind the scenes and continuing to rob and pillage the country as he had done for almost nine years.

The SA business and investment community was overjoyed. Colin Coleman of global investment giant Goldman Sachs was effusive in his praise for this development and his comments made it to the front page of the Business Times, the business section of the Sunday Times. ‘SA tipped to be the hottest emerging market country in the world,’ screamed the headline, with almost half a page devoted to all the good things that were heading our way.

Asset managers also got on the bandwagon

Not to be outdone, our asset managers also got on the bandwagon, with Old Mutual, for instance, in March 2018 going around the country and telling its 12 000 or so financial advisers that SA was set to be the best investment destination in the whole world over the next 5 years. This forecast even made the front page of Business Day, which normally is a bit more circumspect and somewhat critical of South Africa’s investment performance.

For a brief period – December 2017 to January 2018 – some foreign money poured into the country and the rand strengthened to around R11,80 to the US dollar, but that honeymoon didn’t last long.

Even formerly more perspicacious commentators were also sucked into this bout of good news, generally named ‘Ramaphoria’.

Here is an extract from Alec Hogg’s Biznews newsletter of 29 March 2018:

‘With so much noise about, one needs to look in the right places for answers. And when it comes to the economic future of South Africa under president Cyril Ramaphosa, there are few better positioned to guide us than a direct adversary from his old labour union days, former Anglo exec turned futurist Clem Sunter.’ Sunter puts it succinctly, “If he shows the positive qualities which I know he has from frequent meetings with him when he was the leader of the NUM, we have a chance of moving back once more to the High Road trajectory. If he is overwhelmed by internal divisions inside his own party, or by outside forces which render him powerless, the Low Road beckons with an extreme ending not to be dismissed.”’

Six issues

Hogg went on to say that Sunter put the High Road probability at 60%, ‘but says this will require skilful addressing of six issues: firm treatment of the corrupt; a turnaround in the education system; inclusive leadership; replicating rather than eliminating SA’s pockets of excellence; opening the economy to everyone; and sensible management of land reform. Get those right, he says, and SA is on track for the 5% economic growth rate needed to make a meaningful and sustained dent in unemployment. Mess up on those six key challenges and the current Low Road will continue. Some good news in all this, though, is Sunter puts the prospect of the country declining to Zimbabwe-like chaos at just 10%. Ahead of the ANC’s December vote, that would have seemed hugely conservative.’

Well-known political commentator Max du Preez was, at around the same time, quoted as follows on the website, The Phoenix: ‘Imagine a post-Zuma South Africa, a changed political environment of perhaps coalitions ruling in provinces and local councils, clear economic policies and a more efficient and accountable civil service. I can realistically imagine an SA in the not-too-distant future with a 6% growth rate, an exchange rate of R10 to the US dollar, declining unemployment, a transformed education system and a new optimism replacing anger, intolerance and depression. I can imagine a time soon when we South Africans can hold our heads high again in the world as we did immediately after 1994.That’s the SA we should work hard for. I want to be part of that SA and the battle to get there.’

Foreign investors have voted with their money

But here we are, 30 months down the road. The High Road is dead and buried. As president of the country, Cyril Ramaphosa has done very little to address SA’s immediate needs, apart from confirming the ANC’s commitment to expropriation without compensation, a national health insurance as well as more stringent applications of BEE.

And, every now and then, indulging in a little bashing of the remaining whites in the country about their history of colonialism, apartheid atrocities and white monopoly capital. Not exactly the investment-friendly policies he was spouting when he addressed the World Economic Forum and other seminars when he was holding out a begging bowl for more than R500bn of investments.

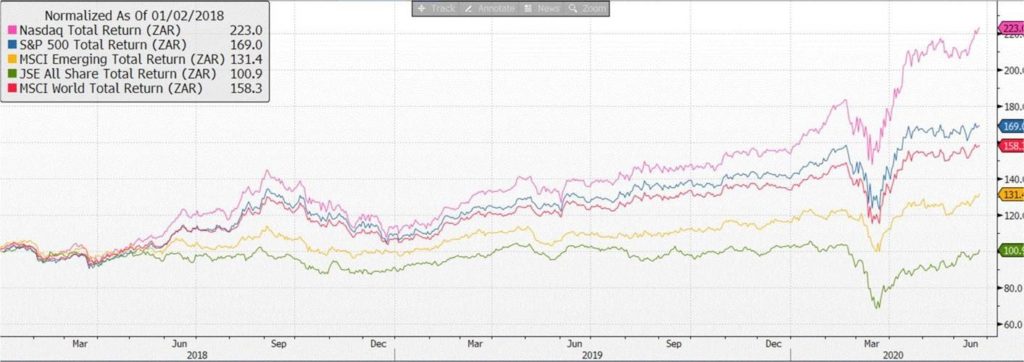

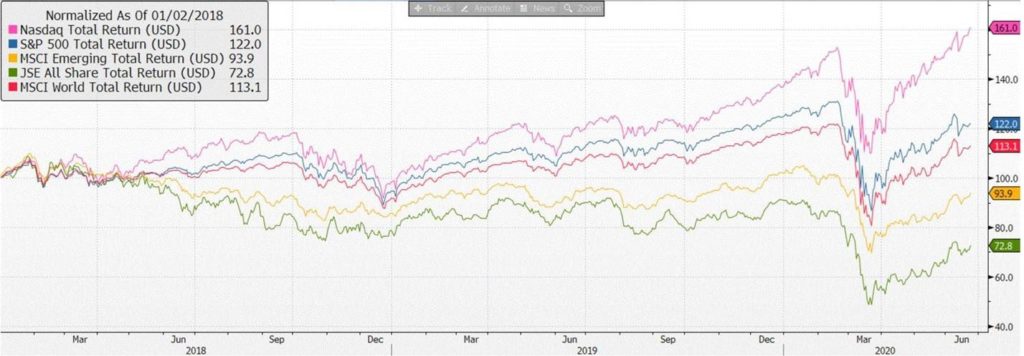

The JSE has shown no growth in rand terms, while in dollar terms the decline has been about 30%. Offshore markets have on a relative basis left South African investors in the proverbial dust. Pension and retirement funds are being ground into the dust, with returns of between 0% and 3% per annum now becoming the norm.

How is it possible that so many – ostensibly smart and clear-headed – commentators could get it so wrong? And that those who warned – as I did – that all is not as it seems, were banished to the sidelines when it came to media commentary?

JSE versus Main Markets (ZAR and USD)

The economy has shown very little growth since President Ramaphosa took over, business and consumer confidence is at record lows, while Moody’s, the last of the three large credit ratings agencies that still had some hope left for South Africa, finally pulled the downgrade-level at the end of March, just as the Covid-19 pandemic crashed onto our shores.

Dashed all hope

This dashed all hope of any economic recovery and, by 24 June, when finance minister Tito Mboweni delivered his (redacted) Supplementary Budget speech, it was clear that we were witnessing an economic implosion, the likes which the country has never experienced.

I say ‘redacted’ because, during a post-Budget interview, Mboweni asked his director general Dondo Mogajane ‘what happened to the chapter about regulation 28?’, which immediately prompted the Twittersphere to light up about prescribed assets and fears that pension and retirement funds would come into the firing line to stop the fiscal bleeding. Come October, when the Medium-Term Budget is delivered, we will know for sure.

GDP growth is forecast to decline by between 5% and 7% this year, and unemployment has gone above 30% for the first time (40% if you include people who have stopped looking for work), but the big shocker has been the almost total collapse of tax revenues, which – though no big surprise – leaves a fiscal hole of more than R300bn.

SA’s budget deficit as a percentage of GDP is now set to reach 68% this year and rise steadily to 85% in 2023, after which, Mboweni promised, it will come down. Closing the hippo’s yawning mouth, as he said.

Real and growing threat

But ratings agencies Fitch and Moody’s were quick to comment that they do not believe this will happen, which leaves the very real and growing threat that – within six years or thereabouts – South Africa may not be able to repay even the debt on its massive mountain of debt. Late last month, our gross national debt was R3,9 trillion – about a trillion more than early in 2019.

Every man, woman and child in the country has a debt of R71 000 today, and rising. It can never be repaid.

In 2009, South Africa’s debt to GDP was a mere 25%. Since then – mostly under the control of Pravin Gordhan – this debt has doubled and then more, with the government going on a spending spree reminiscent of the most profligate banana kingdoms Africa or South America can offer. This year, it could reach around 70% for the first time ever, a level unthinkable a few years ago, even among the most critical commentators. We don’t have much to show for it.

Most of this was on salaries, wages and perks for the 1.3 million civil servants. Earlier this year it was revealed that more than 29 000 civil servants earned a basic salary of more than R1m.

New utopia

Oh, to be a civil servant in this new utopia. Guaranteed job – income – medical aid and then pension for life. Who wants to run the risk of going into the private sector –unless you are the recipient of a fat, juicy tender?

South Africa is now increasingly being compared to Argentina, notorious for its regular and frequent debt defaults. Lesetja Kganyago, governor of SA Reserve Bank is fighting a formidable battle against the modern monetary theorists within the ANC who advocate massive spending by the central bank, warning that such a move could cause a sudden massive collapse in the currency.

Recent history shows the Argentinian peso dropping from 3 to the USD in 2002 to 68 currently. Debt defaults also come with the re-introduction of currency controls. When last did you hear of Argentine tourists coming to SA?

Virtually the only good thing to have come from the budget speech of 24 June is that most informed South Africans now have a fairly good idea when we will have our sovereign debt crisis – around 2025/26. And we can now plan for that.

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR

If you like what you have just read, subscribe to the Daily Friend