Book review: Cambodia: From Pol Pot to Hun Sen and Beyond

Sebastian Strangio (2020)

Cambodia is one of the most fascinating countries on Earth. It was the centre of one of the great Old World civilisations, reflected in the temple complex of Angkor Wat; it suffered an episode of terror in the 1970s that rivals that of the Holocaust, and is the only country in the world to have had its governance taken over by the United Nations (UN). And in its history and current situation there are parallels that South Africa can observe and learn from.

Following a visit there in 2017 I have developed a keen interest in the country, and would recommend Sebastian Strangio’s new, updated book, Cambodia: From Pol Pot to Hun Sen and Beyond, as essential reading for anyone with an interest in this South-East Asian nation.

Strangio, an Australian journalist based in Thailand, who spent nearly ten years in Cambodia, gives an in-depth account of Cambodia’s recent history, from the coup that overthrew the monarchy in 1970 to the civil war that led to the rise of the Khmer Rouge in 1975, the subsequent Vietnamese occupation and continuing civil war, the UN administration, and Cambodia’s re-entry to the family of nations and its apparent flowering as a democracy. As with most things, the truth is far more complex than appears at face value and it is in Cambodia’s ‘democratic’ experience that some parallels with South Africa can be drawn.

Strangio also shows how Hun Sen, who has governed Cambodia since 1985, has reinvented himself, to remain in power.

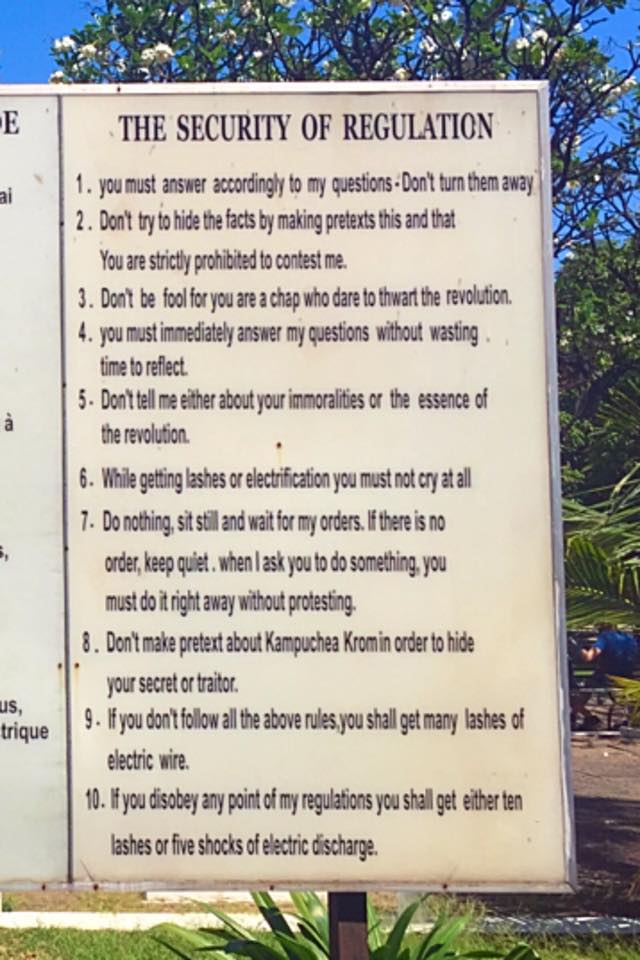

Strangio gives a concise history of modern Cambodia and a chilling overview of the scale of the atrocities carried out by the Khmer Rouge, easily one of the worst mass murdering regimes in history. Blinded by their own ideology, its leader, Pol Pot, and his comrades no longer saw human beings as people with their own hopes and dreams but rather as tools to be used to shape an agrarian utopia, which soon turned into a nightmare. The Cambodia of the late 1970s, when a quarter of the population died through targeted killings, starvation, and forced labour, was, along with the concentration camps of World War II, the violence of the Congo Free State, and the Soviet gulags, as close as we have come to creating Hell on Earth in the 20th Century. This is something human beings are sometimes unfortunately too good at. As a prosecutor speaking at the trial of Khmer Rouge commanders who were finally brought to justice in the 1990s says: ‘There are few graver threats to humanity than those posed by those so blinded by ideology, beliefs, or religion that they are willing to do anything, to employ any means, however destructive or unlawful, to achieve their goals.’

Cambodian insurgents

The Khmer Rouge were overthrown in 1979 by the Vietnamese army (who subsequently occupied the country for ten years), supported by Cambodian insurgents, including Hun Sen.

Strangio then lays out how Hun Sen, who had defected from the Khmer Rouge in the 1970s, rose to power in the 1980s, eventually rising to head the communist state that succeeded Democratic Kampuchea, as Cambodia was known under the Khmer Rouge.

The People’s Republic of Kampuchea (PRK) was what Cambodia was known as in the 1980s. However, despite the overthrow of the Khmer Rouge, much of the international community continued to recognize the Khmer Rouge as the legitimate government of Cambodia. Cold War politics meant that countries such as the US and UK would not recognize the Vietnamese-backed PRK, as the Vietnamese themselves were in the sphere of influence of the Soviet Union at the time.

However, it was the end of the Cold War which saw the impetus for change in Cambodia, and was, to a large degree, what drove reforms in South Africa. The global community, enamoured with the ‘End of History’ thesis and the spread of liberal democracy, saw Cambodia as fertile ground for the flowering of liberal democracy. This was not unlike the global interest taken in South Africa at the same time.

The global community threw its considerable weight behind rebuilding Cambodia, and the country became the first (and, so far, only) country to have its administration taken over by the UN. In 1992 and 1993, the world body ran the country, administered elections, and began putting in place institutions (including the restoration of the monarchy) which would see Cambodia (it was hoped) become a shining beacon of democracy.

In the beginning it seemed that this had worked. Hun Sen renamed his Kampuchea People’s Revolutionary Party the Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) and embraced the free market. To outside observers it seemed as if the country would soon leave its authoritarian and statist past behind.

The UN-administered elections, held in 1993, saw the CPP, to its great surprise, come second to the wonderfully named and acronymed National United Front for an Independent, Neutral, Peaceful and Cooperative Cambodia (Funcinpec), a royalist political party. However, with neither the CPP nor Funcinpec securing a majority, the two went into an uneasy coalition. Through a combination of shrewd political manoeuvring and outright violence (which led to what was effectively a self-coup in 1997 by Hun Sen) the power of Funcinpec was broken and the party has never regained the influence it had, despite the reverence which most Cambodians have for their Royal Family.

Fright at the polls

A number of parties and individuals, notably Sam Rainsy, have risen in the 21st century to challenge the hold of the CPP and of Hun Sen on power. However, once again using a combination of violence, political cunning, and a pliant judiciary, Hun Sen has seen off most challenges. After Sam Rainsy’s Cambodia National Rescue Party gave the CPP a fright at the polls in 2013, the pliable judiciary soon saw the opposition banned. In the 2018 elections the CPP faced only token opposition (including from the much-reduced Funcinpec, many of whose leaders were co-opted into the CPP) and it won all 125 seats in the country’s Parliament.

South Africa is, by contrast (and at the risk of using a cliché) a vibrant democracy, and it is unthinkable that a major political party could be banned on a flimsy pretext, as happens in Cambodia.

Nevertheless, there are parallels between the two countries.

A rapacious elite in Cambodia funnels much of the country’s output to itself, which is one of the factors blocking political reform. As Strangio notes, ‘true reform would undermine the very economic interests that sustained it’. Not unlike South Africa.

At the same time, there is often one law for the top dogs and another for everyone else, as we are seeing in South Africa currently, with former President Jacob Zuma’s disgraceful refusal to obey court orders. This country is certainly not at the same level as Cambodia yet, where mistresses of cabinet ministers get doused with acid by the bodyguards of the minister’s wife with no consequences, or where a non-compliant judge can be quietly moved from the capital, Phnom Penh, to become a magistrate in some sleepy jungle town.

Uppity activists, who have not managed to secure ties or contacts abroad (and are thus less protected from the worst excesses), are killed or thrown into jail on flimsy pretexts. Moneyed individuals, with links to Hun Sen and other members of the Cambodian elite, are effectively a law unto themselves, forcing people (often violently) off land that they have stayed on for years.

Corruption is also a key factor in Cambodian life. In some ways South Africans are still amateurs compared to Cambodians but one can certainly see our country following the trail blazed by Cambodia, among others.

South Africa is not Cambodia, but there are parallels in the way institutions are white-anted, ordinary people are ground down by the powerful, and the trappings of democracy are often as superficial as lipstick on an authoritarian pig.

Hopeful note

But Strangio ends on something of a hopeful note. Cambodia has left its past as an insular hermit kingdom behind. Strangio notes that Phnom Penh is not unlike other Asian capitals where hip professionals hang out in coffee shops and trendy bars. It is increasingly plugged into the world (internet access and the use of smartphones has grown rapidly in the past 20 years), and this also means its people can look past Hun Sen and the CPP. Expectations are rising and Cambodians are demanding more – not just in terms of material goods and infrastructure but in terms of accountability and fairer politics. Again, this is not unlike South Africa – where, though we have not reached the end of the era of African National Congress dominance, we are perhaps at the beginning of the end.

Cambodians and South Africans both face uncertain futures, but in both countries there is also, perhaps, hope that the future will be better, as the old certainties crumble.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend