Poverty and hunger appear to be persistent problems, and many people hold capitalism in general, and neoliberalism in particular, responsible for perpetuating them. This is a mistaken belief, and the data prove it.

There is a widespread belief among the left-leaning mainstream that the persistence of poverty and hunger is evidence that so-called ‘neoliberal’ economic policies have failed. The belief is that they perpetuate or worsen inequalities, and only benefit the rich at the expense of the poor.

Ever since the financial crisis of 2008, there has been talk of the failure of neoliberalism, both worldwide and in South Africa.

During the negotiated settlement that snatched peaceful elections out of the jaws of civil war, the country ‘came depressingly close to charting a redistributive alternative that envisioned a central role for the state in promoting development’, wrote William Shoki wistfully in the Mail & Guardian, but instead embraced neoliberal orthodoxy in deference to powerful countries and global financial institutions.

On this, all of the country’s subsequent economic problems, from high unemployment to low growth, can be blamed, they would have you believe.

Misdefinition

Despite its frequent use among left-wing academics and commentators, neoliberalism as it is understood today isn’t really a thing. The fellow who coined the term in 1982, Charles Peters, then editor of the Washington Monthly, used it to describe something entirely different from its modern meaning: ‘If neo-conservatives are liberals who [in the 1970s] took a critical look at liberalism and decided to become conservatives, we [neo-liberals] are liberals who took the same look and decided to retain our goals but to abandon some of our prejudices. We still believe in liberty and justice and a fair chance for all, in mercy for the afflicted and help for the down and out. But we no longer automatically favor unions and big government or oppose the military and big business. Indeed, in our search for solutions that work, we have come to distrust all automatic responses, liberal or conservative.’

Instead, critics of capitalism have co-opted the term to describe what really are just classical liberals. The economic policies today described as neoliberal describe the ideas elaborated by classical liberal economists like Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman, and by the 1980s, came to be associated with politicians such as Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher.

The best description comes from David Harvey’s 2005 book A Brief History of Neoliberalism: ‘Neoliberalism is in the first instance a theory of political economic practices that proposes that human well-being can best be advanced by liberating individual entrepreneurial freedoms and skills within an institutional framework characterized by strong private property rights, free markets, and free trade.’

Although Harvey is highly critical of neoliberalism, this describes policies that any classical liberal would gladly endorse. These principles long predate Reagan, and Hayek, for that matter. But for the sake of consistency, let’s stick with the neoliberal label that is used, pejoratively, to describe classical liberal economics.

One simple graph

The campaign for so-called ‘social justice’ and against neoliberalism has spread worldwide, in anti-globalisation protests around the world, various Occupy movements in the US and the UK, the Yellow Vests in France, and the Social Outbreak in Chile. Sporadic outbreaks of unrest around the world, and in South Africa, all take aim at the supposed dangers of neoliberalism.

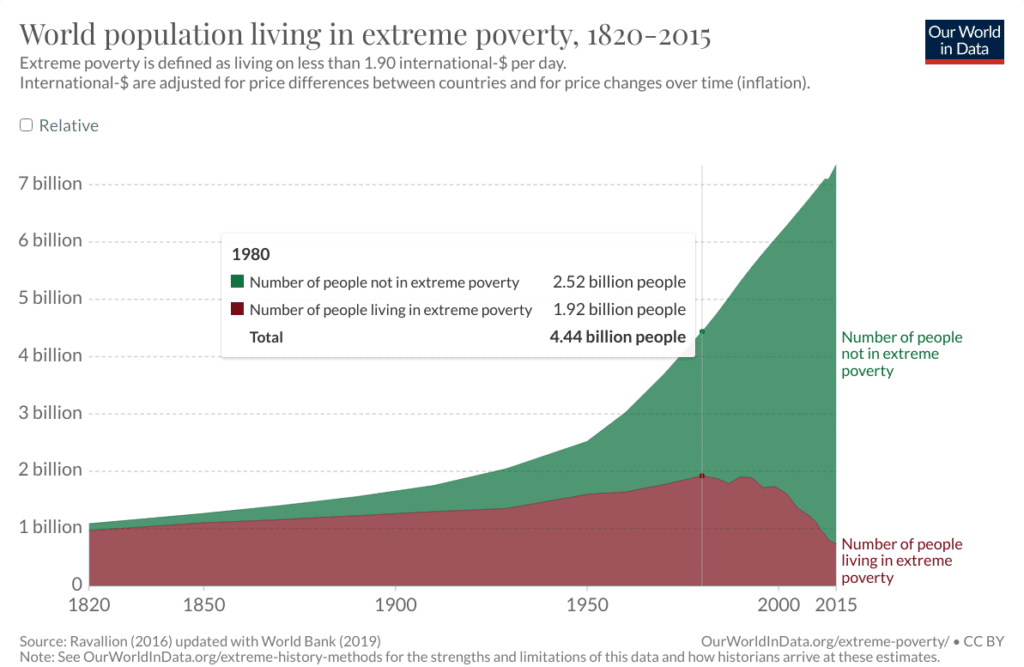

All of this vitriol, however, is dispelled by one simple graph:

It is poetic justice that the peak of extreme poverty in the world occurred in 1980, the year that Ronald Reagan began his first term.

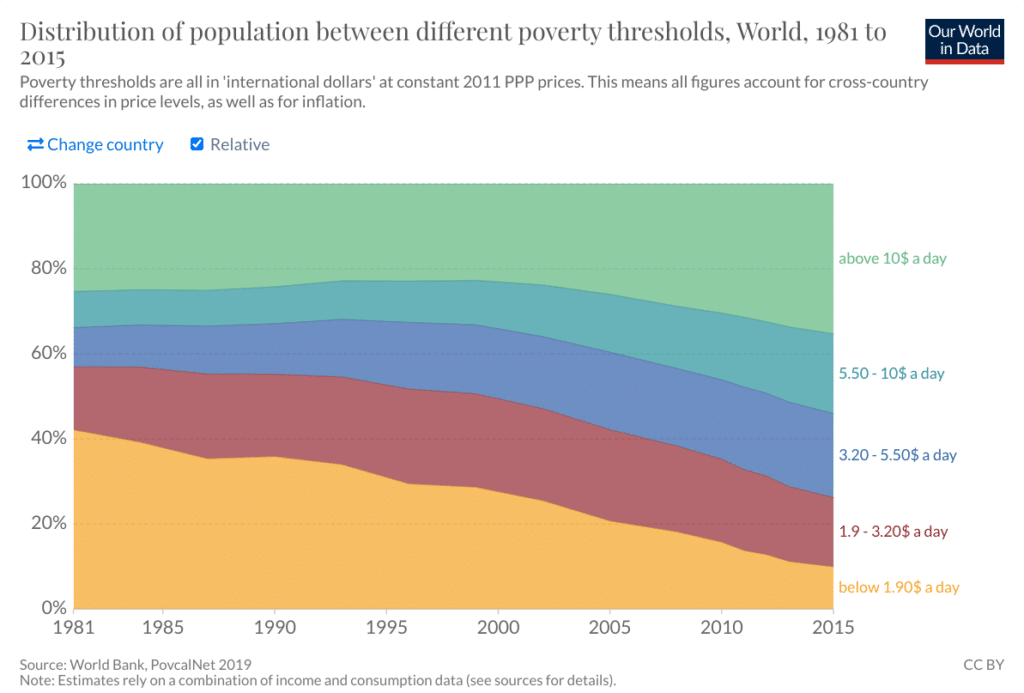

Many people will try to argue this graph away by complaining about income levels above extreme poverty, but there’s a chart for that, too:

This shows that no matter what income level you choose to define poverty, the share of the world’s population below that line – adjusted for inflation and purchasing power parity, of course – has consistently declined since 1999.

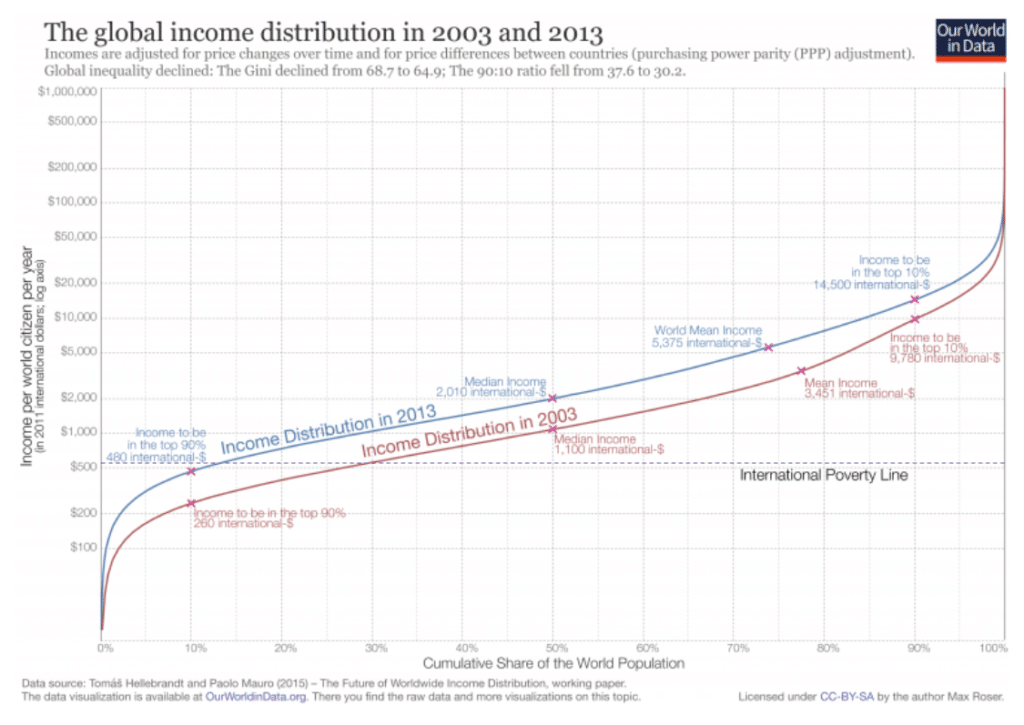

Another way to look at this is to consider how global income distribution per person has changed over a given period. Note that similar improvements are evident at all income levels, despite the financial crisis which fell smack bang in the middle of this decade:

This trend doesn’t hold for every individual country. In some rich-world countries, middle-class and lower-class incomes have stagnated in recent years. Still, this is not a global problem, and as we shall see later, cannot be blamed on neoliberalism.

Ignorance

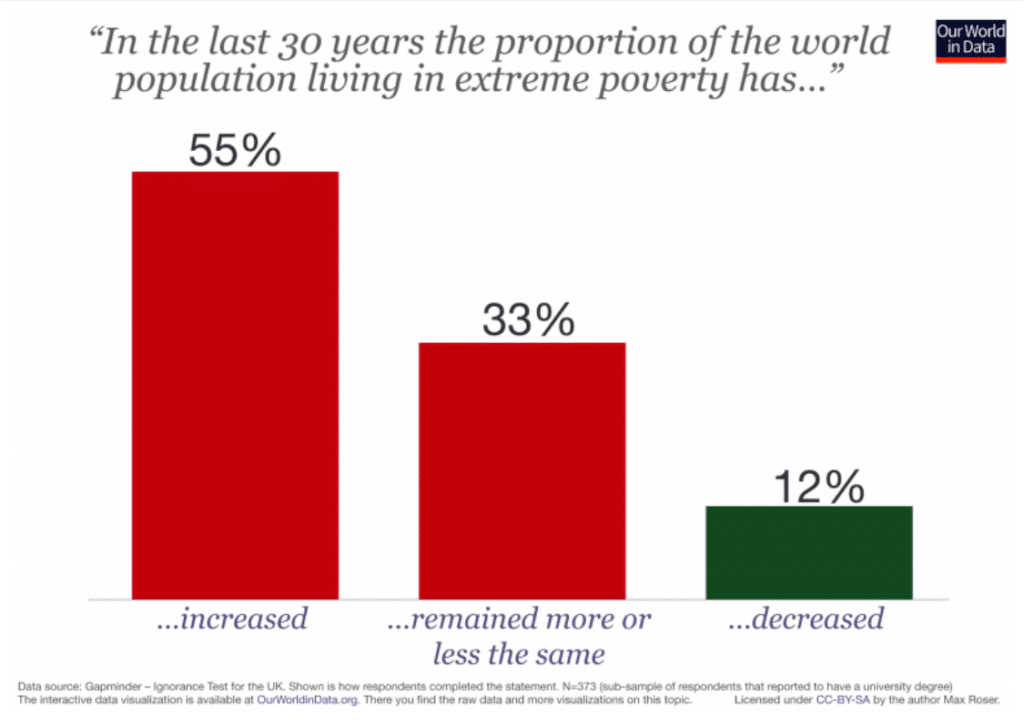

Despite the dramatic decline in both the share of people living in poverty and the absolute number of people living in poverty, surveys show that almost nobody knows this. This is from a survey conducted in the UK:

(For an interesting look at all the things people think they know that just ain’t so, see the Gapminder Ignorance Project by the late Hans Rosling.)

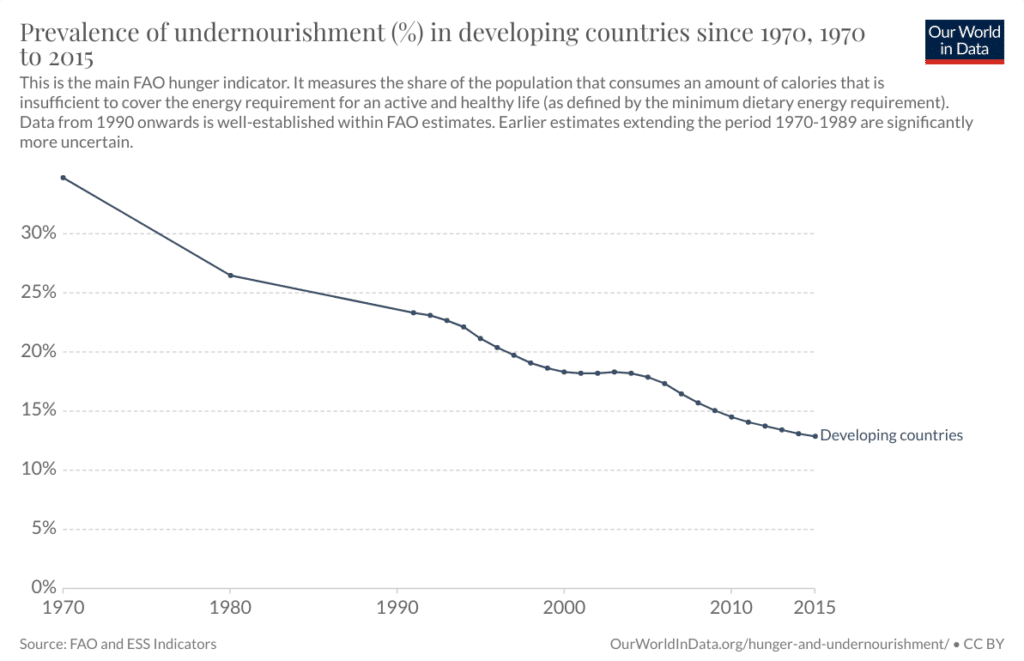

A similar trend can be seen in the number of people who suffer from undernourisment around the world:

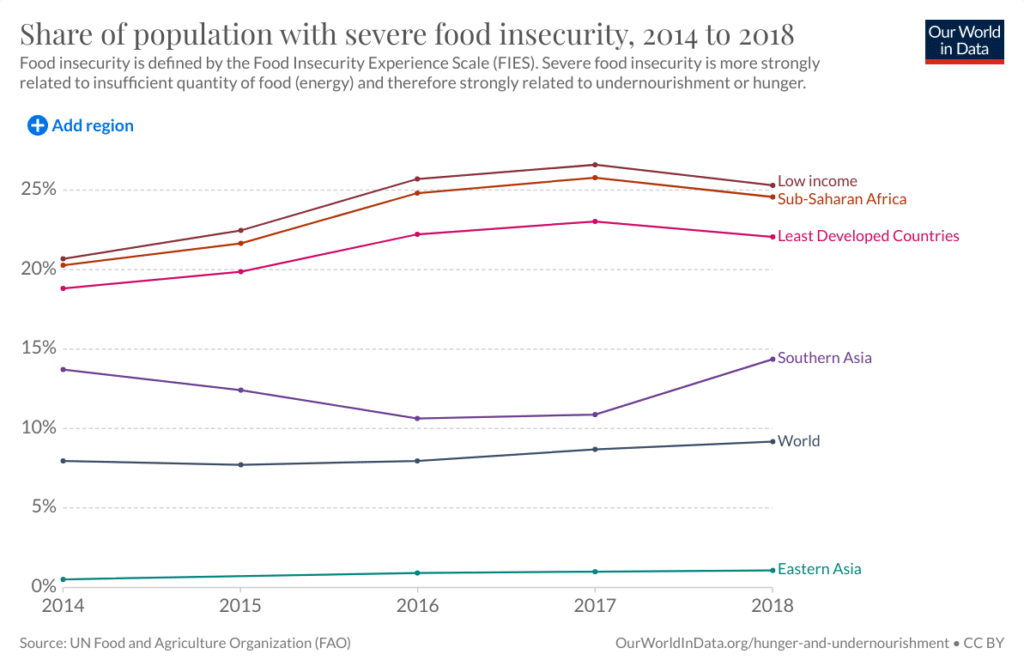

That chart only goes to 2015, which hides an uptick in food insecurity in recent years:

While troubling, this is not enough to negate the long-term trend.

The global poverty and hunger situation has been exacerbated tremendously by the calamitous economic shutdowns imposed on most of the world in response to the Covid-19 pandemic. Some 150 million people are expected to join those still stuck in extreme poverty this year, according to the World Bank, which amounts to a four-year setback in global poverty reduction.

Still, that’s not enough to reverse the long-term trend.

Inequality

To explain all this away, the anti-neoliberal left point to inequality. The thing is, apparent inequality might be a useful stick with which to stir discontent, but it is not a problem in itself. The absolute living standard of the poor is what matters.

The question then becomes, where poverty and hunger persist, what are the policies that cause this?

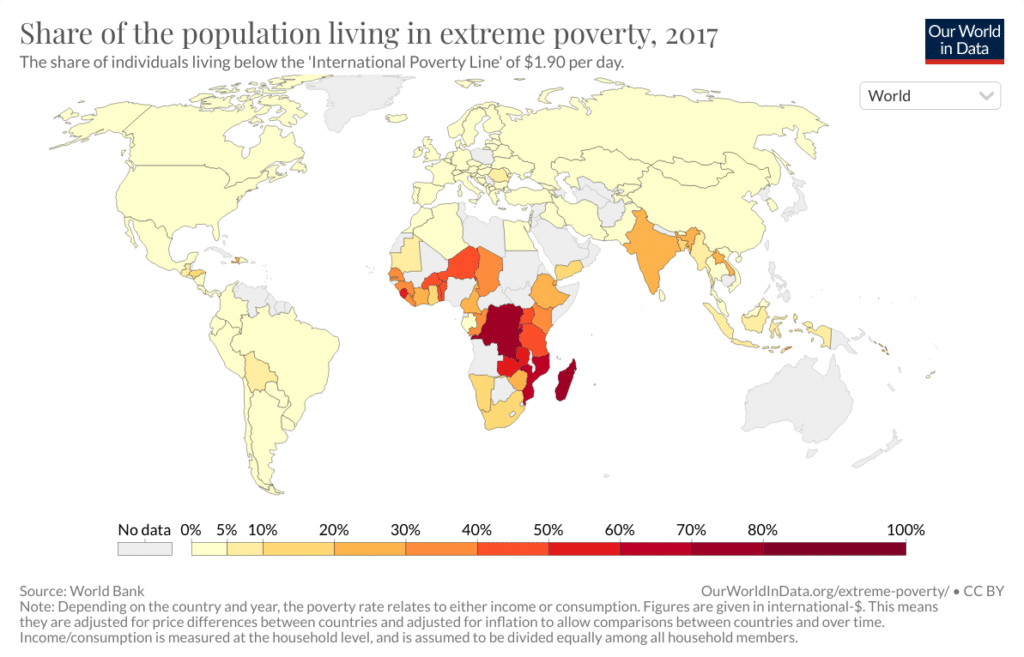

So, here is where poverty persists:

Those are not exactly poster countries for neoliberal economics, are they?

Chile, which was a desperately poor socialist quagmire by the 1970s, became famous for being a pioneer of neoliberal intervention by the Chicago Boys led by Milton Friedman during the regime of Augusto Pinochet, is now ranked in the top third of countries in the world by GDP per capita (adjusted for purchasing power, World Bank 2019). It is also ranked in the top quartile of the most economically free countries in the world.

Yet despite almost every economic indicator showing great and sustained improvement in Chile’s lot (GDP per capita almost quadrupled, low inflation rate, sustained decreases in poverty rates), the mainstream left must complain about something, and duly blames the Chicago Boys for inequality.

Economic freedom

In general, a wide variety of economic freedom measures – that is, neoliberal economic principles – is strongly correlated (see pp.18-21) with a variety of social welfare indicators, such as higher income per capita, higher life expectancy, lower infant mortality, higher income earned by the poorest 10%, lower poverty rates, and even higher gender equality.

By contrast, the countries where poverty and hunger persist tend to be socialist, lack sound and effective economic institutions, suffer corruption in the relationship between government and big business, or are at war.

In South Africa, the economic policies under presidents Nelson Mandela and Thabo Mbeki, though pretty strongly left-leaning and redistributionist, are often described as the most neoliberal of all post-Apartheid presidencies. They were turfed out in favour of the ‘radical economic transformation’ (i.e. socialism and corruption) of Jacob Zuma.

Yet it was under Mbeki that post-Apartheid South Africa enjoyed its glory years of sustained 5% growth and its lowest unemployment rate.

Things weren’t exactly hunky-dory. Even 5% wasn’t enough growth to make a real dent in unemployment and poverty, but things were pointed in the right direction. If Mbeki was the neoliberal, we need more of that, not less.

Government intervention

Even in the capitalist West, a lot of the ills of modern economies, such as income stagnation and growing inequality turn out not to be the fault of free markets, but of government interventions in the market.

The biggest culprit is quantitative easing, which is the largest redistribution programme from the poor to the rich in modern times.

It is no surprise that the rich got richer during the pandemic, and stock markets were flying even as the real economy tanked. When governments print unlimited money, and hand most of it to the rich, they’re going to pump it into assets like stocks, property and cryptocurrencies. Those are exactly the prices that have skyrocketed as the money supply increased at ever-increasing speed.

(Most central banks are nominally independent of government, but they do enjoy a government-protected monopoly on issuing money, so the distinction is not crucial.)

Those were the prices that skyrocketed during the easy-money 1990s, under the ‘maestro’, Alan Greenspan, which inflated the dot com bubble, which inevitably burst. To cushion the crash, the Fed kept interest rates low, and that easy money went straight into properties, inflating a bubble which inevitably burst in 2007. To cushion that crash, interest rates were reduced, often to zero, and central banks started printing money.

Astute readers might see a pattern develop, as Ron Paul did in 2001, when he predicted the development of the housing bubble in exquisite detail. Most people, however, keep thinking that booms and busts are just a natural feature of the markets. They’re not. They’re caused by government intervention.

A broad measure of the US money supply started rising more sharply after the 2008 financial crisis, but has jumped by a third since the beginning of 2020. It’s absolutely insane, and there’s no end to it, as Biden prepares to spend trillions more. Other central banks have done much the same, although the South African Reserve Bank – not being able to back massive money printing – has been a little more restrained.

How the economic consequences of monetary policy can be blamed on neoliberalism and free markets is quite beyond me.

Follow the data

If the data shows us anything, it’s that the policies that have pejoratively come to be known as neoliberalism are exactly the policies that have made such great inroads into poverty, hunger and health. They are the policies that can pull poor countries up by the bootstraps and make them rich countries.

The left might not like it, but to maintain their myth that free markets are a problem, they need to tell catchy lies, like ‘the rich are getting richer while the poor are getting poorer’.

Neoliberalism is better described as classical liberalism. Poverty and hunger persist not because of it, but because there isn’t enough of it. If we want to turn this country (and the rest of sub-Saharan Africa) around, we need more Chicago Boys, making economies more free. The proof is in the data.

[Image: billy cedeno from Pixabay]

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend