Ominous warnings written by environmental activists are designed to whip up public opposition to oil and gas production off the South African coast. We should see those warnings for the propaganda they are.

‘Total’s Garden Route oil and gas extraction plans bode ill for rights of the area’s vulnerable communities,’ read the headline in Daily Maverick on 28 March 2021. The ‘op/ed’ was written by Linda Arkert, an ‘environmental social worker’ (whatever that is) living in the Little Karoo.

She works as a specialist researcher for The Green Connection, a lobby group whose raison d’être is ‘opposing oil and gas exploration’.

‘Africa’s history has shown that the voracious behaviour of multinational oil and gas companies,’ read the blurb, ‘combined with corrupt and under-capacitated governments, spell disaster for the environment and the human rights of poor and marginalised people living in affected areas.’

The vaguely-specified ‘extraction plans’ by Total presumably refer to major gas discoveries at the Brulpadda and Luiperd prospects in the Outeniqua basin. Both are about 175km offshore, almost due south of where I live on the Garden Route coast.

A great many oil and gas exploration wells have been sunk closer to the coast between Mossel Bay and Cape St. Francis, notably by the South African oil and gas company Sungu Sungu and the state-owned national oil company PetroSA, but environmental activists far prefer to demonise ‘voracious multinational oil and gas companies’.

In truth, large multinationals with major brands to protect are likely to be the most benign players in the oil and gas sector. Smaller, lesser-known firms likely have less experience with health, safety, and environmental procedures, nor do they command the fleets of training and compliance officers that a large multinational would have.

Emission cuts

Arkert’s first substantive objection is that ‘one could argue that this discovery represents a major threat to South Africa’s already half-hearted commitment to emission cuts in the Paris Climate Agreement’.

Sure, one could. But one could also argue the exact opposite. In a country where 77% of primary energy supply comes from coal, and open-cycle gas turbine power stations burn diesel, switching to natural gas would be a major improvement.

Gas halves carbon dioxide emissions, and virtually eliminates all other pollutants, compared to oil and coal.

In the US, the natural gas boom which started in about 2005 and dethroned ‘King Coal’ as the primary source of electricity generation, coincided with a dramatic decline in carbon dioxide emissions. In absolute terms, despite robust population and economic growth, US emissions are down 13.5% from their peak in 2005, which takes them back down to early-1990s levels. Per capita, US emissions are at their lowest level since the early 1960s.

So one could definitely argue that the discovery of major offshore gas reserves heralds a new era in carbon dioxide emission cuts for South Africa.

Legislation

Arkert argues that ‘South Africa’s mineral and petroleum legislation, in its current form, has no framework for regulating offshore exploration and exploitation’. This is a half-truth, designed to mislead.

Hitherto governed under the Mineral and Petroleum Resources Development Act of 2002, oil and gas projects will fall under a dedicated new law once the Upstream Petroleum Resources Development Bill is passed by Parliament. This law makes detailed provision for regulating the sector, including its environmental management.

Arkert’s argument then devolves into the claim that nobody in government could possibly be competent enough to mitigate the environmental risks. Perhaps this is true, but if so, that would apply to any industry.

This might be a reason to improve government capacity for environmental oversight, but it cannot be a reason for preventing all new productive ventures. That would only serve to further destroy the country’s economy, and, to quote Arkert herself, ‘the marginalised and poor will bear the brunt of this’.

Her first reference to ‘Africa’s history’ involves the case of Shell in Nigeria. That case, however, is very different from any plausible South African scenario.

For a start, all oil and gas operations in Nigeria are majority owned and controlled by that country’s state-owned oil company, and not by the multinationals with which it has partnered. Second, most oil spills in Nigeria are caused by sabotage, and not operational accidents.

Nigeria is internally not at peace, and the government has ridden roughshod over the rights and economic interests of the people who actually live in the oil-producing regions. Arkert mentions a court case in which Shell Nigeria was ordered to pay compensation for oil spills, but that case remains open to appeal, and while I doubt Shell can shirk all responsibility, it seems unfortunate that the Nigerian government isn’t alongside it in the dock.

None of the circumstances that surround Nigerian oil drilling are applicable to South Africa, however. The same is true for the land-based drilling Arkert references in Mozambique and Uganda. This is about offshore dilling in South Africa, not onshore drilling elsewhere in Africa.

There is no reason to expect a South African offshore oil and gas industry to be anywhere near as vulnerable to pollution or other harmful consequences as they were in Nigeria, Uganda or Mozambique.

Unless, of course, oil and gas are nationalised, and the national government goes to war against the Western Cape. In that case all bets are off, but I’ll bet the rebel province would need oil and gas.

Pollution

‘Will exploiting these resources do more harm than good?’ she asks, referencing the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. Although that was certainly a disaster, cherry-picking rare disasters is propaganda, not science.

Let’s try to put that spill into perspective. It was the largest accidental spill in history, but it was dwarfed by the largest deliberate spill in history, which happened in the Persian Gulf during the first Gulf War.

In total, however, spills from oil and gas production, including both Deepwater Horizon and the Persian Gulf disaster, account for only 3% of all the oil in the ocean.

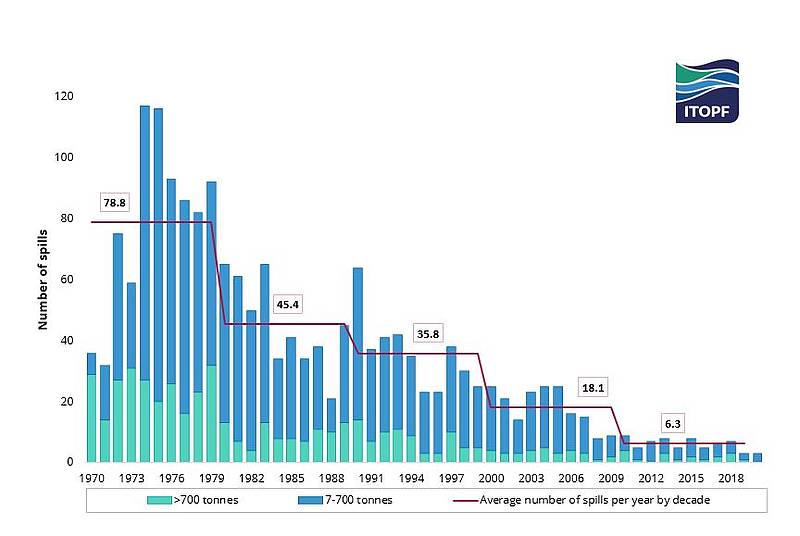

This is hardly a vast amount. Transportation spills involving oil tankers dwarf production spills, at 12% of all the oil in the ocean. And those have been on a steep downward trajectory as the industry adopts increasingly stringent safety measures.

The use or consumption of oil, which includes operational discharges from ships and discharges from land-based sources, account for 37% of all the oil in the ocean, or more than 12 times the contribution from production. Photos of an oil-slicked beach might make good propaganda, but it is not representative of the real situation.

The largest source of oil in the ocean, bar none, is Mother Nature herself. Natural oil seeps produce 46% of all the oil in the oceans. Oil is, after all, biodegradable.

If this doesn’t destroy Arkert’s argument, consider that she referenced an accident involving oil drilling, which is hardly a reasonable example to hold up when you’re trying to scare people about the dangers of drilling for natural gas.

Vulnerable communities

Like many environmentalists, who themselves tend to belong to the wealthy elite, Arkert makes much of ‘the marginalised and the poor’.

The problem is that the marginalised and the poor in the Southern Cape are vanishingly unlikely to be affected by offshore gas drilling, at all. Even communities that rely on small-scale fishing are highly unlikely to notice any impact on their livelihoods whatsoever.

Even if the worst happens, there is no reason to believe that these communities would in any way be stripped of their rights, as Arkert’s headline suggests. There is also no chance of the forced removals, violent conflict, or any of the other horrors that Arkert invokes.

The Green Connection submitted comments on the draft scoping report published as part of the Environmental and Social Impact Assessment conducted by SLR Consulting on behalf of Total E&P South Africa. The final scoping report is available here.

It is notable that these comments are largely limited to legal and procedural technicalities and the possibility of a ‘worst-case scenario’ oil spill following a well blowout, and do not mention any of these other horrors either. Presumably that is because they cannot be justified in a formal, legal document.

Notably, the website of The Green Connection claims that the risk of oil spills is high, but the group’s formal comments neglect to challenge the claim in the scoping report that the probability of a well blowout is extremely low.

And while the group insists that a spill of Deepwater Horizon magnitude should be modelled in the planning, it does not recognise that Total will be drilling for gas, not oil.

The upside

On the upside, there is a chance that a vibrant oil and gas industry could create employment opportunities, in the upstream sector itself, in downstream industries, or in a broader industrial economy revitalised by a large domestic source of natural gas. It could certainly contribute to a more reliable electricity supply and lower electricity prices for consumers and industry alike. This would directly benefit the ‘poor and marginalised’ over which Arkert frets.

In a region like the Garden Route, where the largely tourism-based economy was devastated by Covid-19 lockdowns, the upside benefits significantly outweigh the potential downside risks.

Not that you’d hear that from someone whose primary objective is to oppose all oil and gas drilling, no matter the circumstances, as a matter of fixed ideology.

Public-interest lobby groups would serve the country much better if they could play a critical role in public consultation in good faith. Instead of mustering any argument, however weakly supported, in resolute opposition to industrial development, they might instead support the opportunities for economic growth, but with reasonable, science-based conditions designed to minimise negative environmental and socio-economic impacts.

All else is propaganda, and is just as unreliable and dishonest as anything you might expect from corporate special interests in the oil and gas industry, if not more so.

Image by gloriaurban4 from Pixabay

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend