This is the first of a five-part series setting out why South Africa blew up a week ago, arguing that the blow-up was not due to a planned insurrection, that the experience will not see the government change tack and reform, that the country will destabilise further, and suggesting what you should consider doing to survive the consequences. The analysis is based on our initial thoughts, read against our long-standing advice. We will add to it, and so improve it, over time, but are confident that the bones of it are right and will hold up to future critical scrutiny.

I am indebted to James Myburgh of www.politcsweb.co.za for last week drawing my attention to a letter that Mao Tse Tung wrote to his disillusioned revolutionary comrades nearly a century ago to shore up their flagging confidence in a Chinese revolution. That letter does an excellent job of explaining what happened in South Africa just over a week ago.

A fuller extract was published by the Daily Friend yesterday, but I quote, here, the closing paragraph, because it gets the South African analysis so spot-on.

Mao writes:

‘….Because of the growth in government taxation, the rise in rent and interest demanded by the landlords and the daily spread of the disasters of war, there are famine and banditry everywhere and the peasant masses and the urban poor can hardly keep alive. Because the schools have no money, many students fear that their education may be interrupted; because production is backward, many graduates have no hope of employment. Once we understand all these contradictions, we shall see in what a desperate situation, in what a chaotic state, China finds herself. We shall also see that the high tide of revolution against the imperialists, the warlords and the landlords is inevitable, and will come very soon. All China is littered with dry faggots which will soon be aflame. The saying, “A single spark can start a prairie fire”, is an apt description of how the current situation will develop. We need only look at the strikes by the workers, the uprisings by the peasants, the mutinies of soldiers and the strikes of students which are developing in many places to see that it cannot be long before a “spark” kindles “a prairie fire”.’

The social deprivation that Mao describes is, to my mind, the primary causal factor behind last week’s riots. In a note to clients of the Centre for Risk Analysis (CRA) this week, I explained that South Africa was littered with ‘dry faggots’:

‘Start with jobs; between 1994 and 2007 the number of people with a job roughly doubled. Yet whereas 14.5 million people had a job in 2007 the figure for today is only 14.9 million. In terms of schools; roughly 4% of children will pass maths in matric with a grade of 50% or higher. In terms of real per capita GDP; the figure today is lower than that of 2007. In terms of welfare; the grants rollout has slowed of late and the increase in the value of grants has not kept pace with inflation as experienced by poor households.’

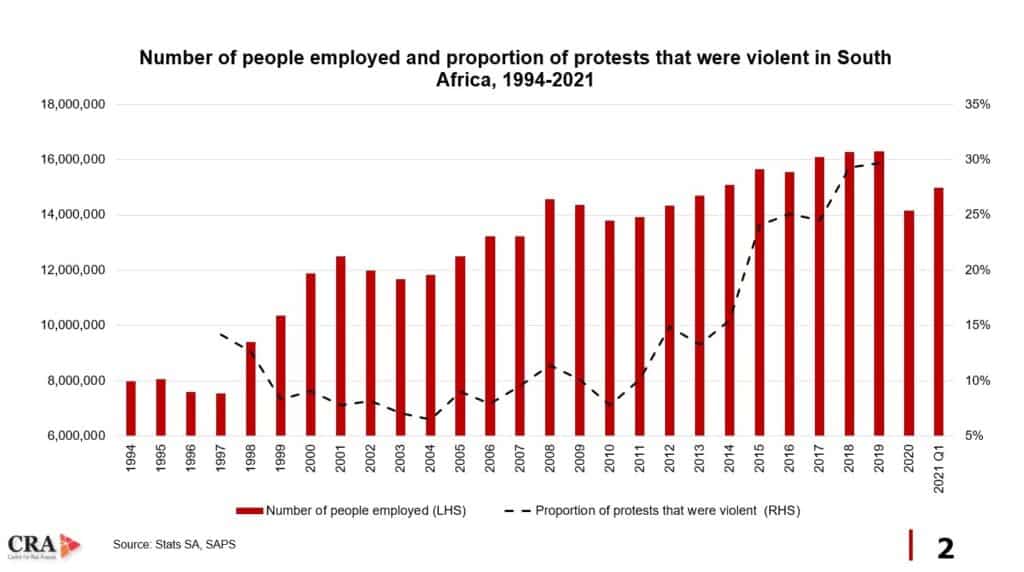

I also explained that, as a consequence of such deprivation, South Africa’s political destabilisation is much further advanced than most investors understand and analysts admit: ‘(There) are now many more people who don’t vote than the number who vote for the ANC, amongst people below the age of 50 ANC support has fallen to below 50%, and the number of violent protests in the country was last year 400% higher than in 2007 whilst almost a third of all protest incidents were violent, up from 10% in 2007.’

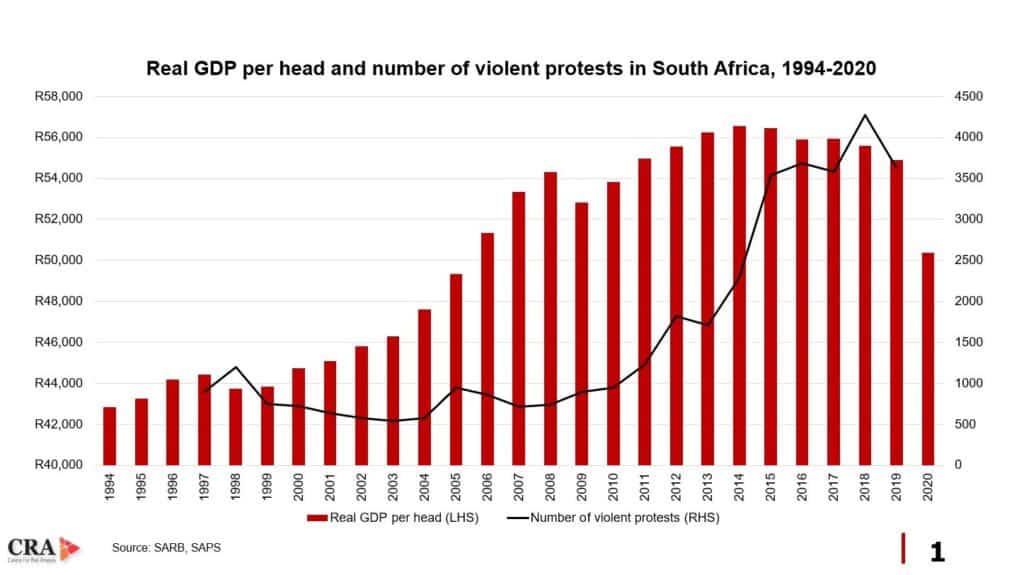

The relationships between the socio-economic and the political have been apparent to us for the better part of the last two decades. Look, for example, at the chart below – which is drawn from a current CRA client briefing and tracks almost twenty years of real per capita GDP data against the number of violent protest actions in South Africa – and you will see how as the economic indicator slowed the protest indicator rose.

Or look at the next chart – tracking what proportion of protest actions are violent against the total number of people with jobs – and you will see how as job growth slowed the intensity of protest action increased.

We have scores of similar charts to inform our thesis that this past week’s blow-up is best explained by examining the state of the prairie rather than by dwelling on the sparks.

As in China of the 1930s, ‘the rise in rent and interest demanded’ is crushing many households, especially after the consequences of South Africa’s foolish economic lockdown (South Africa enforced an economic lockdown without the capacity to provide stimulus to small businesses and people who lost their jobs) and its enforcement by the government’s ‘National Coronavirus Command Council’, the very notion of which was spectacularly undone over the past week.

It is true in many parts of the country that ‘[hunger,] is prevalent’, and there is undoubtedly ‘banditry everywhere’, while it is indisputable that ‘the peasant masses and the urban poor [struggle] to keep alive’. Education is mainly hopeless and ‘many students fear that their education may be interrupted’, while government policy is so hostile to investment that ‘production is backward, [and] many graduates have no hope of employment’.

Mao described present day South Africa to a T – or at least the IRR’s long assessment of it over the past decade – in writing that, ‘Once we understand all these contradictions, we shall see in what a desperate situation, in what a chaotic state, [South Africa] finds herself’. And he understood that because of that ‘chaotic state’ ‘(we) shall also see that the high tide of revolution against the imperialists, the warlords and the landlords is inevitable’ and that it ‘will come very soon’.

- Read the next part of the series on why South Africa’s blow-up was not a coup attempt or an attempted insurrection in the Daily Friend tomorrow.

[Image: Suhas Rawool, Chickenonline from Pixabay]

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend