Some years ago I found myself on a tattooist’s reclining chair with tiny needles jabbing at the skin on my ribcage.

I was studying philosophy and had recently attended a trance party, so a tattoo seemed like the obvious next step on my way towards enlightenment. Naturally the tattoo needed to be in a foreign language and it would need to be profound, full of meaning. People were going to ask me about it, after all.

In the semester just before getting inked, as they probably say, I attended one of the more influential lectures in my time as an undergraduate at Stellenbosch. The prof had handed us a paper in support of a deontological theory of moral action the day before and had asked us to read it in preparation for class that day.

On the way to class I rehearsed all the clever things I was going to say. The class began and the prof asked us what we thought of the paper. We loved it, most of us said. Made so much sense, sir, I likely said. He asked for a show of hands from those who were deontologists (believing that morality is based on certain axiomatic principles regardless of outcomes). I would say that about ninety percent of the class raised their hands. It was a done deal. The matter was settled, for me anyway.

The prof then spent all of fifteen minutes exposing the flaws in deontology and instead argued for utilitarianism (an action is right if it leads to the greatest happiness for the greatest number). I felt something shift in my mind as he spoke.

Making mistakes is a given. We know this about ourselves. What we learn from them is what matters. That day I learned I was a persuadable idiot who should never be given access to a lever anywhere close to a train track on which people happen to be tied.

The prof’s takedown of deontology was thorough and fun to watch. With the job of unravelling my intellectual certainty having been completed, the prof asked for a show of hands from those who were now utilitarian. I’d say that most of the class were categorically in favour. And then one guy near the front asked: ‘What about you, sir?’ To which the prof answered that he was a deontologist. He smiled as he said this. He knew what he had done and I thank him for it.

Quintessential non-committer

Armed with newfound introspective capabilities, I vowed never to jump to a conclusion before hearing both sides of an argument. Boy, but I was intellectually humble then, and I knew it. The quintessential non-committer, that was me. I had made a vow after all. If only everyone in the world was as wise as I was just then, what a world we would live in!

South Africa’s elite schools are steadily giving in to the whims of radical activists with authoritarian tendencies. The results are beginning to bear fruit.

Teachers and students self-censor for fear of offending someone and falling foul of HR departments and diversity committees. School policies fawn over safe spaces meant to protect the community from ideas that someone, somewhere has deemed harmful.

School leaders around the country are bending over backwards to signal that they are inclusive of all kinds of races and beliefs before reneging on the latter. Inclusivity sounds good until you realise that in most cases it involves official and unofficial bans on speech acts and opinions thought to be exclusive of those from identity groups assigned vulnerable status.

Inclusivity means that teachers are not allowed to greet their classes with ‘good morning, girls’. ‘Good morning, class’ is preferable. Inclusivity is forcing stakeholders to declare their pronouns, thus endorsing a kind of radical gender ideology that remains contested. It is telling pupils what they ought to believe, as one school in Joburg has it in their anti-discrimination policy:

Do not “believe that because you have experienced discrimination in some form, it is the same thing as experiencing structural racism” or “believe that friendship with a few black people means you are non-racist. It takes more than that.”

Inclusivity is banning the word ‘monkey’ in any context. Rather, as one schools has it, refer to them as ‘vervets’, or, as another prefers, ‘primates’.

‘Chink’

Inclusivity is, as one teacher recently told me, being called out by your own English class for reading the word ‘chink’ as it appears in Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream in reference to two characters communicating through a gap in a wall. Inclusivity is trying to explain to your class that context is important, that ‘chink’ is a common English word, that Shakespeare’s was not being racist towards Asian people, and having your class double-down on their accusation.

Inclusion is the outright banning of ‘colour blindness’ – as in not forming an opinion of somebody based solely on the colour of their skin.

Most tellingly, though, inclusion is activist teachers and consultants refusing to debate or even consider an idea that challenges their own. I know because I have tried. Inclusion looks like what would have happened if my philosophy lecturer had noted the show of hands in favour of his position, moved on to an unrelated topic, and treated those who did not raise their hands as bad people.

Ultimately, people should be free to believe any totalising ideology they like. However, requiring children and colleagues to accept beliefs or else face ridicule, re-education and punishment is detrimental to the liberalism which the country is already hanging on to rather precariously. Inclusion does not have to wear this face.

Style and humility

I loved school. I remember engaging in good-natured debates with my teachers and classmates, particularly in English and history classes. My favourite teachers were the ones who moderated class discussions on controversial topics with style and humility, the ones who played devil’s advocate. They were teaching that there are two sides to an issue and it is important to understand both before planting a flag in the ground, if indeed it is ever wise to do so.

As my university experience indicates, I did not internalise the lesson fully. In any case, the lesson was implicit. It took a philosophy professor to go out of his way to prove the point for me to understand how human I was. Walking out of that lecture I felt superhuman…

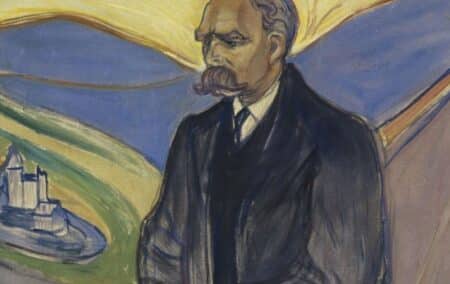

Until the following semester when we were treated to the expertise of an overseas lecturer there to teach us about the German philosopher, Nietzsche. For three weeks, the professor simplified Nietzsche’s confusing aphorisms and showed us the value in his nihilism. Nietzsche ‘got me’. So much so, that one day I headed off to the tattoo parlour, a quote from Thus Spoke Zarathustra in hand.

The needle had barely started buzzing when the tattoo artist asked about the quote I had chosen. It’s Nietzsche, I said. ‘Oh, the “God is dead” guy,’ he mused. So for the next half hour I lay there listening to an improvised altar call, unable and unwilling to respond for the pain (the parlour was called Disciples Ink). That’s the kind of thing that will stick with you.

Despite the trauma I was happy with the outcome. Perhaps even happier about the worldliness I had just acquired.

I had been getting on well with the guest lecturer, and before class the following week, told him about my tattoo. He started laughing. The theme of that day’s lecture was things that Nietzsche probably got wrong. It may as well have been ‘reason’s why Caiden is a persuadable idiot’. One of the first ideas up for discussion was the one etched into my skin.

Be warned, your idiocy can sneak up on you

My tattoo may be a garbled and obscure endorsement of a German philosopher’s ideas about nihilism translated into French, but to me it quite clearly reads: Be warned, your idiocy can sneak up on you at any time. It is my favourite tattoo.

Intellectual humility is illusive. It counts for naught unless you are reminded of the times you have fallen short of it and understand the gravity of such an occasion. Sometimes this may require a vivid memory of a nice Christian man poking you with a needle and saying ‘Jesus loves you’ for you to take the lesson seriously. For schools it might take the persistent and courageous efforts of humble teachers and parents, working together, to tirelessly prod and poke schools, pointing out the dogmatism currently dominating the education space.

Schools that listen and introspect are the ones who will survive the illiberal assault on their institutions by activists unwillingly to consider other points of view.

School leaders, teachers and students will make mistakes as they navigate the fast-changing modern world. But I think that it is better to have the freedom to make mistakes and learn from them rather than have mistakes forced on you by a dogmatic group of ideologues. As the stoic butler in Kazuo Ishiguro’s The Remains of the Day laments: ‘I can’t even say I made my own mistakes. Really – one has to ask oneself – what dignity is there in that?’

But I could be wrong.

[Image: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Friedrich_Nietzsche#/media/File:Friederich_Nietzsche.jpg]

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend