This Week in History recalls memorable and decisive events and personalities of the past.

8th July 1099 – Some 15 000 starving Christian soldiers march in a religious procession around the besieged city of Jerusalem as its Muslim defenders look on

‘Taking of Jerusalem by the Crusaders, 15th July 1099’ by Giraudon, from the Bridgeman Art Library

The First Crusade was remarkable. Thousands of people, nobles and peasants alike, across the Western Christian world, swept up in a frenzy of religious zealotry, encouraged by the Pope (you can read more about it in this edition of This Week in History), set off on what they saw as an armed pilgrimage to the Holy Land, to the Levant.

While some of these groups failed to make it to the Holy Land, either running out of supplies, becoming distracted or being killed by the Seljuk Turks, to the surprise of everyone, a significant force of tens of thousands, mostly of French-speaking people, not only fought their way through the Turks but managed to secure the city of Antioch in 1098 after a desperate and closely fought siege.

These nobles would found the first ‘Crusader State’, a principality ruled over by Western Christians, which governed mostly Jewish, Muslim and Eastern Christian subjects and relied heavily on military support from knightly orders or scattered crusading nobles.

Detail of a medieval miniature of the Siege of Antioch from Sébastien Mamerot’s Les Passages d’Outremer

After their victory, the nobles of the First Crusade established the Principality of Antioch. But many were not willing yet to abandon the crusade. Antioch was an important city to the early Christians, but the true prize remained the city of Jerusalem, where Christ had been crucified. After some disputes over which of the leaders of the Crusade was to receive Antioch, pressure from the lower-ranking members of the Crusade forced the leadership to continue on to the city of Jerusalem.

As the army marched towards the city, the Islamic rulers of the region, the Ishmail Shiite Fatimid Caliphate, realised they did not have the troops in the area to stop the crusaders and asked for peace. This was refused.

So the Fatimid governor of Jerusalem, Iftikhar al-Dawla, began to prepare the city for siege; he expelled all of the Christians from the city – Antioch had fallen because a local Christian had opened a gate for the Crusaders – and assembled a force which included 400 elite horsemen. He stockpiled supplies and poisoned all of the local water wells outside the city.

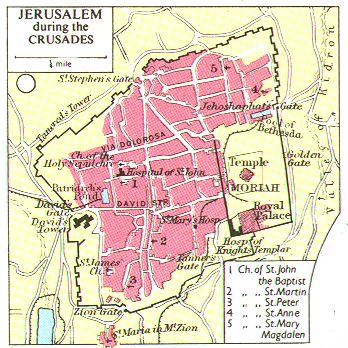

Map of Jerusalem as it was during the Crusades

On 7 June 1099, the crusaders overcame the outer fortifications around Jerusalem and split into two groups to lay siege to the city from both north and south.

They launched their first attack on the city’s 15-metre-high walls on 13 June, but this failed.

On 17 June, the crusading army received news of the arrival of Genoese and English ships carrying the equipment needed to construct siege weapons, and set about collecting wood for the construction of these weapons.

Medieval and ancient sieges were a complex contest of willpower, logistics and luck.

Both sides were vulnerable to disease, both sides often struggled to feed themselves and both sides were in constant fear of surprise attacks. The defenders had an additional fear, that of treachery. It was standard practice in medieval sieges that if a city resisted a siege, that if it fell, it would be subject to a sack. The longer and fiercer the resistance, the more violent a sack.

13th-century miniature depicting the siege

If a city fell to an assault rather than surrender, the sack would be an unrestrained orgy of looting, rape, murder and vandalism. So, the defenders were constantly weighing up the prospect of victory; if the attackers looked like they could take the city by storm or outlast the defenders it would be better to surrender. The garrison was often more willing to fight than the inhabitants of the city and sometimes fighting would break out between the soldiers and the civilians if the city decided to surrender but the garrison did not.

Both sides would play extensive psychological games with each other, attempting to convince the other it was hopeless, often complete with shouting matches over the walls or displays of willpower and toughness.

One of these efforts began on 8 July as the crusaders, suffering from a severe lack of supplies, attempted to intimidate Jerusalem by marching in a huge religious procession around the city, showing off their numbers and their religious fervour.

A few days later they finished their siege weapons, two massive siege towers, a battering ram capped with iron, wattle screens to protect the attackers from arrows and a large assortment of ladders.

On 14 July 1099, the attack on the city commenced.

By the end of the day some of the walls had been captured, and when the assault began anew the next day, the crusaders broke into the city and began to massacre the Muslim and Jewish residents in what turned into a brutal sack. Iftikhar al-Dawla, however, managed to escape and would continue as the governor from the city of Ascalon.

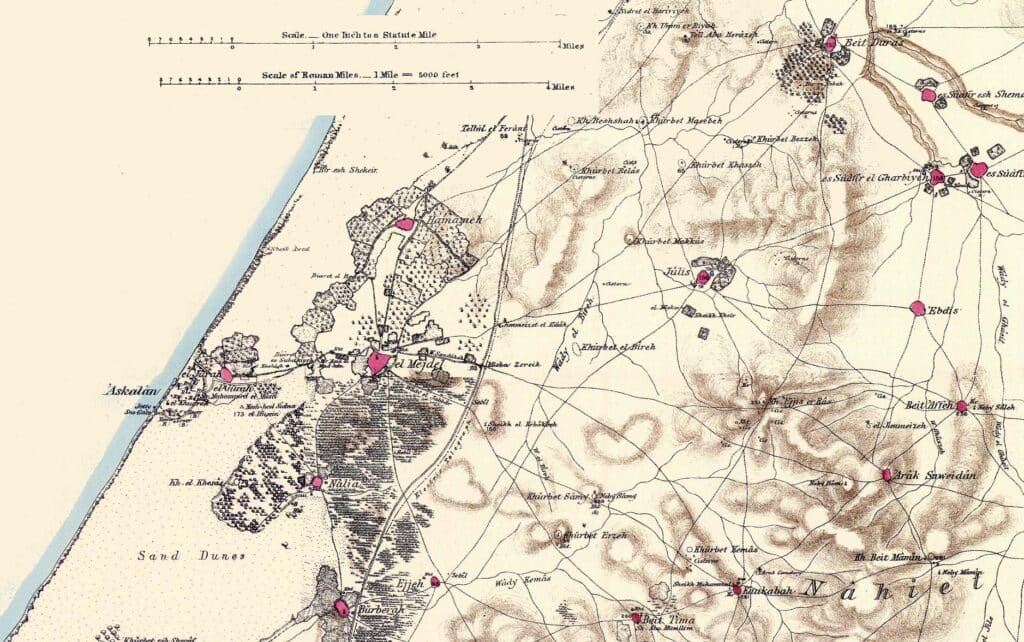

The ruins of Ascalon are shown on the left in this image from the 1871-77 Survey of Palestine, covering the area of modern Ashkelon

A few days after the sack, during which the streets were said to have run red with blood, the crusaders held a church service and declared the Kingdom of Jerusalem with one of the crusade’s leaders Godfrey of Bouillon as the first King of Jerusalem.

Godfrey of Bouillon being created the Lord of the city of Jerusalem, from the Histoire d’Outremer by William of Tyre

The Kingdom of Jerusalem would last until 1291.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend