Here is a case of bloody, curious entertainment, with a political twist. It’s a long story, so tuck in.

It starts last week when South African Dricus du Plessis defeated a former middleweight champion of Mixed Martial Arts (MMA) at the UFC 290 in Las Vegas. That sets Du Plessis up to fight the reigning champion in September.

It is worth expanding on the scene of victory, an octagonal UFC cage, as if in real time with some comments to underscore the ‘vibes’, which are Colosseum-cum-Vegas. (Remember the absurdly deep epic movie trailer voice that used to narrate blockbuster synopses? Feel free to use it for the phrases in parentheses that follow.)

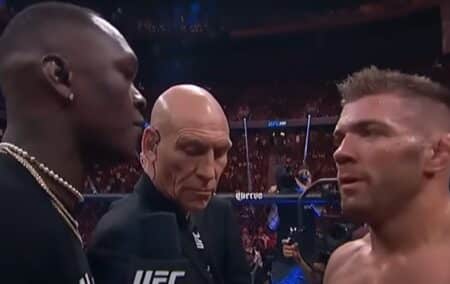

Du Plessis climbs out of the cage to shake hands with former US President Donald Trump. (Heavy handshake). Then he does a post-fight interview with the world’s primo podcaster, Joe Rogan (11 million listeners per episode), to talk victory. Enter the danger, Israel Adesanya, a Nigerian-born New Zealander and current UFC middleweight champion who vaults into the cage. (Extra!).

Rogan has the mic: ‘Here comes the great Israel Adesanya!’ (Amazing physique.)

Du Plessis whispers into the mic: ‘I don’t know about great.’ (Ooh, cold dig.)

Adesanya takes the mic. The athletes stand toe to toe. (Face-off!)

Adesanya, building to crescendo: ‘Relax, this is my African brother right here, yeah nigger, what’s up bitch? Yeah nigger, yeah nigger. What the fuck you goin’ do nigger?! Yeah, my African brother, yeah, my African brother, what’s up nigger?!’ (Whoa, that escalated.)

Du Plessis: ‘I’m African, but I ain’t no brother of yours, son.’ (Fast comeback.)

Adesanya: ‘You my nigger, let’s go!’ (Double-down challenge!)

Du Plessis: ‘What are you saying to everybody in New Zealand?’ (He did backstory research.)

Adesanya: ‘I don’t need a DNA test to know where I’m from. Do a 26 and me and they’ll say I’m from Nigeria. Do a 26 and me DNA test and it will tell you where you’re from. I will show you where you’re from!’ (Epic! Stay tuned to see one man kick another all the way back into ancestral Europe!)

The gladiators look for a moment like they are going to fight not for money, but for honour. (Honour!)

End scene.

Cue press junkets, interviews, blogposts, and countless message-board posts about the upcoming fight. PR time happy.

Bombastic entertainment

The Las Vegas spectacular was one of bombastic entertainment, bloodsport, made-for-YouTube American TV, and the performatively anti-social media. MMA is a serious business at the level of money, fitness, fists, elbows, sweat, blood, chokeholds, and eyeballs. Words, less so. But words are part of the business.

I’ve only watched a few MMA bouts and ‘beefs’, but when something popped up on my feed about a New Zealander calling a white South African ‘nigger’ within sweat-splash range of a former US president that struck me as enough improbabilities in one octagon to merit a few more words on how people use race to try to get under each other’s skin.

In a way Du Plessis started ‘the beef’ between them before the fight by promising to ‘take the belt to Africa. I’m the African fighter in the UFC, myself and Cameron [Saaiman, a UFC junior]. We breathe the African air. We wake up in Africa every day. We train in Africa, we African-born, we African-raised, we still reside in Africa, we train out of Africa! That’s an African champion, that’s what I’ll be.’

This kind of ‘Africa’ braggadocio makes me want to write an earnest explanation of why Du Plessis should feel proud to bring the belt home to the Republic of South Africa, not ‘Africa’. I am one of those old-fashioned patriots who can see that countries matter in ways that continents (with one exception) do not.

But that lecture is probably pointless. Google ‘Dricus du Plessis’ and several pictures pop up of him waving and wearing South African flags. I suspect that he too loves the rainbow nation and was talking up ‘Africa’ less as an attempt to promote the hapless AU than as a way to dig at the dragon lurking in Adesanya’s backstory (but more on that later).

Translated from the Colosseum to the salon, Du Plessis’s ‘Africa’ argument is that insofar as ‘African’ is a worthy status it had better be grounded in a non-racialism reminiscent of former President Thabo Mbeki’s I am an African speech. On the basis of where they were both born but only one lives, works, and contributes, Du Plessis has a stronger claim to being ‘African’ than Adesanya.

Adesanya’s use of the word ‘nigger’ is a clever comeback to this non-racial notion. In most of the US the de facto rule is that black people may call one another ‘nigger’, but white people may never use the word except for reports, art, and science, but sometimes not even then.

Not to be touched

John McWhorter, the resident linguist at the New York Times, penned an essay titled ‘How the N-Word Became Unsayable‘, which pushed back against treating the word like a virus not to be touched. ‘For Americans’ born after 1965, he explained, ‘the pox on matters of God and the body seemed quaint beyond discussion, while a pox on matters of slurring groups seemed urgent beyond discussion. The N-word euphemism was an organic outcome, as was an increasing consensus that “nigger” itself was forbidden not only in use as a slur but even when referred to.’

For an example of this ‘pox’ or ‘taboo’ treatment described above consider this summary of a disciplinary report on Adam Habib, Director of SOAS, University of London. The ‘report notes that the director [Habib] spoke the word in full while trying to say that it should not be used within the SOAS community, and that he has since acknowledged that speaking the word in full was a mistake, for which he has apologized’.

On that view McWhorter would not be allowed to ‘speak’ or write ‘the full word’ even when instructing students not to use it gratuitously. And on this view Greg Patton, a professor who teaches Chinese at a California business school, acted immorally when he pronounced the Mandarin word for ‘that’ while teaching the language because of what it sounds like.

That kind of prohibition imputes such superstitious power to the sounds of a word that McWhorter is right to use labels like ‘pox’ and ‘taboo’ as historic precedents. I like the way McWhorter keeps discussion open. He does not treat the word like a pox too contaminated to touch, nor does he leave open any ambiguous endorsement of its gratuitous use.

But there is a fascinating point of linguistics where McWhorter stops short that I would like to pursue. In the ‘N-Word’ piece quoted above he wrote, ‘I am concerned here with “nigger” as a slur rather than its adoption, as “nigga”, as a term of affection by Black people, like “buddy”’.

This raises the question, was Adesanya actually calling Du Plessis ‘nigga’? Did my transcription err? Maybe it did. On Twitter Adesanya used the second spelling, which fits the pretense that he was being affectionate with his fellow ‘African’.

‘Niggas’ and ‘brothers’

To translate from the Colosseum to the salon once more, Adesanya took up Du Plessis’s ‘African’ non-racial definition, inferred that this notion would make them fellow ‘niggas’ and ‘brothers’ on a non-racial basis too, and played that scene out for all to see. In so doing Adesanya artfully manifested a real life reductio ad absurdum, because not one person watching the face-off thought that the two men were about to hug it out as jolly ‘buddies’ or fellow ‘niggas’.

To the contrary, the men were close to blows. What follows, syllogistically, is that since they are not actually fellow ‘niggas’ they are also not fellow ‘Africans’, as had been premised. Clearing the non-racial version of ‘Africa’ out the way paved Adesanya’s path to a DNA brag that culminated in his threat to beat a white South African back to Europe, or back to his ancestors in the great beyond, or both if the great beyond is as divided as the here and now.

I used some fancy words like ‘reductio’ in this commentary just like MMA commentators have fancy names for forms of grappling, kicking, and punching. But the common facts of combat, verbal or physical, are so readily accessible that everyone in Las Vegas ‘gets’ what Adesanya and du Plessis did to one another, even if they don’t quite know how to explain it.

The final twist may be that the ‘nigga’ spelling is not so simple after all. The full Adesanya tweet after the face-off reads, ‘If you ain’t my brother, you ain’t African!! I will show you where you are from, NIGGA!!‘

At that point, I suggest that McWhorter’s observation that ‘the word was also used in pure contempt’ applies. McWhorter’s own example of pure contempt usage was, curiously, of a Marine from the US’s first ‘Splendid Little War‘ (fought partly in the name of whiteness), who said of well-dressed, Francophone Haitians that they were still ‘real nigs beneath the surface’, so he clearly agrees that ‘pure contempt’ usage can come apart from pure spelling.

There may be a reason for that. The altered spelling implies that the contemptuous user thinks the true spelling would somehow be too powerful to bear.

Contempt makes sense for so many reasons. It sells. Du Plessis is going to try to take Adesanya’s title through violent force. Du Plessis also clearly denied that Adesanya is a ‘real African‘. But the most interesting reason for contempt, in my view, is that it would not just be weird, and unprofessional, for the men to get along nicely, it would also literally be taboo.

‘Let’s be chommies …’

Just imagine if Du Plessis responded to Adesanya’s ‘Yeah my African brother’ line like this. ‘Ja no, you right hey. I know we have to fight later, but for now lemme say you my brother, ja you my buddy nigga, let’s be chommies. We both from the motherland, let’s chill with Floyd and be lekker’. Then Du Plessis tries to hug Adesanya.

Pause to imagine what would come next. A blockbuster.

In that scenario Adesanya would have to punch Du Plessis immediately and furiously, even if it cost him his title and his freedom. The alternative, for a black person in the US mediascape to allow a white man to address him like that in front of cameras, would be a degree of ridicule both offline and online, and outright ostracism that few humans could survive. He would suffer a life of disgrace. Quite seriously I think he would have to leave the English-speaking world.

But the other way round is, roughly speaking, in the US, a joke.

To my mind things would be better if the US adopted a non-racial code of conduct more like the general South African attitude to contemporary uses of the word ‘kaffir’ – simply unacceptable outside the arts, science, and reporting. I have made arguments for why I think this would make for better race-indexed rules about who gets to say what on Two Crickets in a Thorn Tree, but I googled Adesanya and his antics carried me away from rehearsing those arguments.

‘The spirit of China will always guide me,’ Adesanya said in a promo video from his kickboxing days in China. That was a surprise to see. He draped himself in mainland China’s flag to match his trunks as you can see in this serious review of his work in the South China Morning Post, a reputable newspaper.

The ‘Israel Adesanya “Made in China”’ video above shifts from surprise to amusement. He says he was ‘always’ inspired by Bruce Lee and ‘whenever I train, sometimes, I visualize myself in those characters’. He says more. ‘Black outside, China inside. I am Chinese. I’m the black dragon’.

‘I have a Chinese heart’

There is another video in this article, of less reliable origin, where Adesanya says ‘take a look at me, what are you thinking? I am a black man? I come from Africa? Come on, please, look at my heart, haven’t you seen it yet? Yes, I am a Chinese. I have a Chinese heart’.

This is amazing. Adesanya also has a slightly urban English accent, not quite cockney, but not far off. And his name is Israel. Can you say that all with a straight face?

‘A Nigerian Kiwi called Israel, with a Chinese heart, a Pommy accent, three US championships, and a killer flying kick walked into a Las Vegas octagon to call some oke from Hatfield called Dricus a “nigger”’.

Every time I reread that I laugh. It brings together such distant cousins of the English language that I want to give the sentence a small prize, a kind of Mixed Martial Arts award.

Still, I don’t know what the punchline is. Maybe it’s that Adesanya is now training with Mark Zuckerburg, since Zuckerberg has been challenged to fight with Elon Musk as a token of the battle between their pseudo-social media companies, Twitter and Thread. ‘We both have South Africans to deal with‘. The Zucker-Musk fight could be worth R1.8 billion, which is where South Africa’s daily debt servicing costs are headed. Musk followed the challenge up with a proposal for ‘a literal dick measuring contest‘, which might be even funnier, but not as easy to commodify and so unlikely to happen.

The real punchline

Looking back, Adesanya has a laugh about some of the Chinese promo-videos, suggesting that he did not really mean it all and that he was doing it all for the money. I suspect that is the real punchline: the ‘beef’ has raised interest in the coming UFC championship fight.

Thanks to the antics they are going to punch each other for a bit more money, which is exactly how race works. This particular face-off is worth showcasing partly because it’s so amusing. For once the only people who are going to get hurt at the end of it all both want it, and deserve it, as all athletes do.

PS

Like most of my fellow seffers (we have the polling to back it), the only colours I support in the neo-Colosseums are green and gold. I hope Du Plessis will bring the belt home!

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend