In 1982 the US auto industry was fighting for its life. Mired in the deepest recession since the 1930s, 250 000 auto workers were out of work. Unemployment was 11%, car loans 15%. Sales plunged 40% from a record high in 1977. US made cars were losing in quality and fuel efficiency. Imports had surged 35% surge in three years.

Into this malaise strode an unlikely figure, Doug Fraser, an engaging, astute high school dropout who headed the United Auto Workers (UAW) union. In 1979 he won praise for collaborating with Chrysler chief Lee Iacocca on the $1.2 billion government bailout that saved the number three automaker from bankruptcy. Born in Scotland, Fraser was six when his family settled in Detroit in 1917. Starting as a line worker at DeSoto, from 1944 on Fraser advanced through the ranks of the UAW, becoming president in 1977.

Fraser recognized the threat, calling attention to the “desperate situation” the auto industry was facing. The UAW chief launched a twin-pillar approach to resolving the crisis. First, he supported protectionist domestic content legislation that would roll back Japanese auto sales. Two, he urged Japanese car companies to put plants, “not just cash registers” in the US, their biggest export market.

Fraser was forthright in supporting US automakers. “The union and the companies have similar goals,” he said, “the preservation of jobs and strong American companies.” The UAW’s objective, he continued, “was to keep American automakers competitive.” Under Fraser, the UAW had made $460 million in contract concessions to Chrysler.

Stark difference

There is a stark difference between Fraser and current UAW president, 54-year-old Shawn Fain, who began as an electrician at a Chrysler plant in Kokomo, Indiana.

Six months into his job, Fain presides over a union whose power and numbers are greatly diminished. Since 1982 membership is down 70%. There are more retirees than active workers. In 1982 60% of US auto workers belonged to the UAW, today it is 18%. US branded cars had 75% of the market, today it’s 40%.

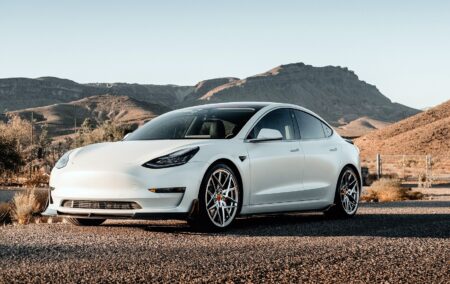

Unlike 1982 or 2009 when General Motors and Chrysler went bankrupt, the Detroit Three face different but equally formidable problems. Today’s challenge is electric vehicles and a cost structure out of whack with the competition. Tesla, the non-union American startup, is producing ten times more electric vehicles than GM, Ford, and Chrysler combined and has a 60% market share.

Even before the strike, costs at the Detroit Three far exceeded those of Tesla and the 16 foreign-owned, non-UAW assembly plants in the US. A line worker at the Detroit Three costs on average (including benefits) $66 per hour compared to $48 at Tesla.

That there are so many Japanese, German, South Korean and Chinese owned auto plants in the US is due in part to Doug Fraser’s persuasive powers. But for the UAW there has been an unintended consequence. To its leaders’ dismay, workers at foreign owned car plants have repeatedly voted against UAW representation. Even German firms—BMW, Mercedes, VW—which at home have union representatives on management boards have rejected the UAW.

Agreements

Labor agreements between the Detroit Three and the UAW typically run from 700 to 1 800 pages outlining in detail work rules, procedures and job classifications.

In the current negotiations Shawn Fain departed from UAW practice. Instead of targeting one company and having that eventual agreement apply to all, Fain is targeting all three companies in piece meal fashion. Fain surprised colleagues by failing to appear at a pre-strike negotiating session with Ford executive chairman Bill Ford, the great-grandson of the company’s founder. Fain similarly snubbed General Motors, not showing up for a planned pre-strike meeting with GM chairman Mary Barra.

Frustrated with Fain’s confrontational approach, Ford CEO Jim Farley has appealed for reason. “Please remember,” he wrote the union, “that Ford, more than any other company has bet on the UAW and treated the UAW with respect. We have been incredibly supportive of the union.” Farley concluded, “the future of our industry is at stake.”

The companies’ Achilles heel is the exorbitant salaries paid to their CEOs. Barra’s compensation was $24 million in 2022, Farley’s $21 million, and Stellantis chairman Carlos Tavares $25 million. This hard to justify compensation has been a gift to the union, whose members wages have not kept pace with inflation.

The disparity between workers’ and CEO pay was at the root of the union’s initial demand for a 40% wage hike. Unlike Tesla where workers receive stock as part of their compensation, the Detroit Three have profit sharing. For 2022 that translated into bonuses of $12 000 at GM, $9 000 at Ford, and $14 000 at Stellantis.

Transition to EVs

The transition to EVs is moving much faster than previously thought. Ford anticipates that 40% of its global production will be electric by 2030. GM expects to be entirely electric by 2035.

The Biden administration wants 50% of all vehicles sold in the US to be electric or hybrid by 2030. The government is offering billions of dollars of subsidies to achieve that goal, including a $7 500 tax credit on EV purchases. California is requiring all new cars sold in the state to be zero emission by 2035.

EV production requires 40% fewer workers. Not surprisingly job protection for power train workers is a top UAW demand. Any Detroit Three settlement—a 20% or 30% wage increase–will widen the competitive gap. Even if Tesla and the transplants increase their wages, the Detroit Three will lag far behind.

Doug Fraser would have done things differently.

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend

Image by capital street fx from Pixabay