This Week in History recalls memorable and decisive events and personalities of the past.

26th October 1947 – Partition of India: The Maharaja of Kashmir and Jammu signs the Instrument of Accession with India, beginning the Indo-Pakistani War of 1947–1948 and the Kashmir conflict

Pakistani soldiers during the 1947–1948 war

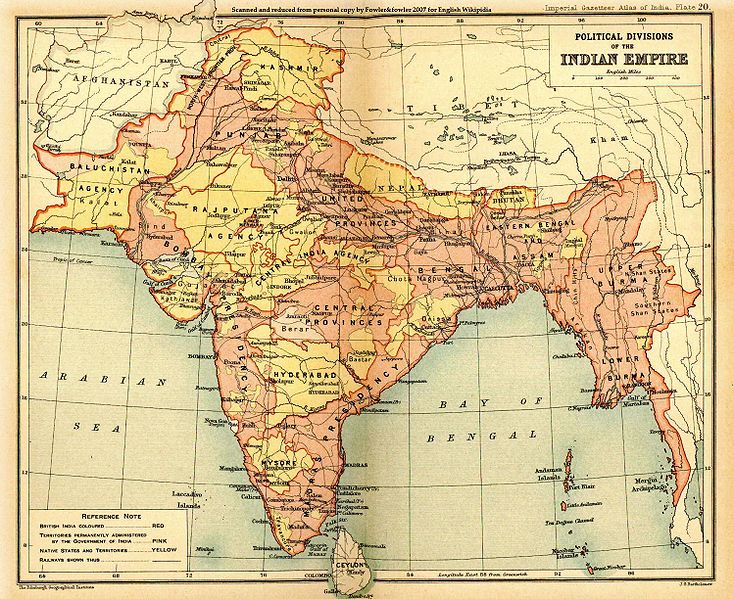

The British Empire in India united the entire subcontinent from the mountains of the Hindu Kush in the west, to the hills of Manipur in the east and to the warm hills of South India.

Within this vast region lived hundreds of millions of people of diverse faiths, cultures, languages, professions and ideologies.

Map titled Political Divisions of the Indian Empire, from The Imperial Gazetteer of India (Oxford University Press, 1909), with British India in pink and the native states in yellow.

As India began to move towards independence in the 20th century, the India nationalist movement which advocated independence began to fracture, as different groups had different conceptions of what they wanted from an India without the British.

The two primary factions which emerged were the Indian National Congress, a secular leftwing movement with some Hindu identity, and the All-India Muslim League, a group which feared Hindu domination of Muslims in a newly independent India and so represented mostly Muslim interests.

While, initially, the League favoured remaining within India, just with significant autonomy and federal powers given to Muslim regions, disputes between Congress and the League meant that in 1940 the League embraced the idea of a separate Muslim country in the north-western regions of British India.

They were opposed by the All-India Azad Muslim Conference, which advocated a united India with a composite Hindu and Muslim identity.

British officials in India overseeing its independence came to favour the position of the League, and – as communal violence between Hindus and Muslims sporadically broke out – the case for an independent Muslim-majority country grew stronger.

Some within Congress also supported the partition, as they believed that Muslim-majority areas would only be allowed to be included within a united India if they had a veto power over the national government, something these Congress members believed would ‘hold back the progress of India’.

So it was that British India would come to be partitioned into two countries, with majority-Muslim areas becoming Pakistan and majority-Hindu areas becoming India.

Complicating matters, however, were the so called ‘princely states’.

These were the remnants of what had once been the numerous feudal lordships and kingdoms which had dotted the subcontinent.

An 1885 photograph of Nawab Bhadur Khan III of Junagadh with his state officials [F. Nelson, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=20337151]

Many had over time been absorbed directly into the British Indian administration, but in many others the prince maintained some control over local affairs.

Upon partition of India, each of these states was given the choice of remaining independent, becoming part of India or becoming part of Pakistan. Most of these were quickly absorbed on independence in 1947, either into India or Pakistan. Two of the larger princely states resisted the central government’s attempts to absorb them. One was the northern state of Jammu and Kashmir, and the other was the large central Indian state of Hyderabad.

The ruler of Jammu and Kashmir, Maharaja Hari Singh, a Hindu, preferred independence, since while his kingdom was majority Muslim, it had significant Hindu, Buddhist and Sikh minorities.

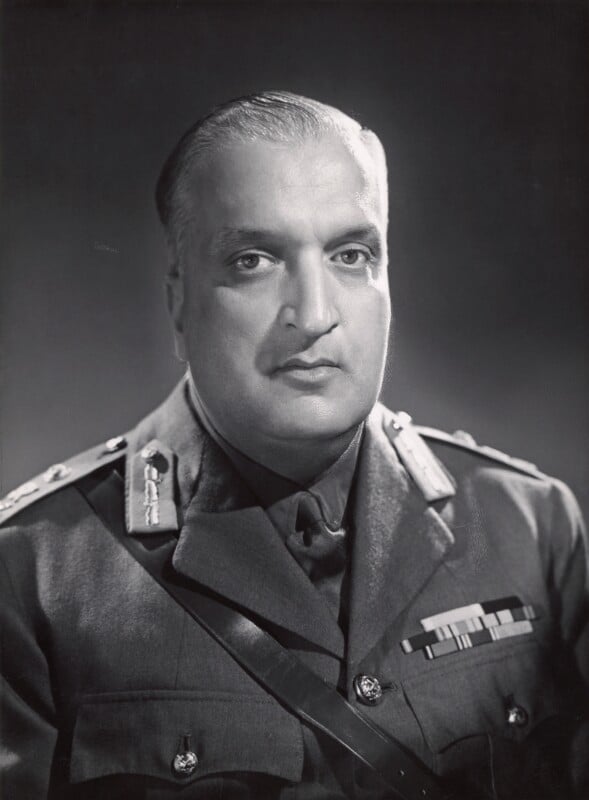

Sir Hari Singh Bahadur, Maharaja of Jammu and Kashmir, the last ruling Maharaja of the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir

He claimed that accession into either Pakistan or India would see significant portions of his population becoming oppressed. He also knew that absorption into either nation would likely significantly diminish his own power. Shortly after Indian and Pakistani independence in August 1947, Pakistan encouraged disgruntled Muslims in Poonch district of Kashmir to revolt.

Hari Singh, after this rebellion was put down, began to grow closer to India and fired his pro-Pakistan prime minister. Pakistan feared that this meant that Jammu and Kashmir would soon join India, and so in October 1947 encouraged another rebellion, this time sending Pakistani troops into the area as well as Pakistani-backed Pashtun tribesmen, who carried out a number of massacres.

Pashtun warriors on their way to Kashmir

Singh, realising he would be unable to resist, appealed to India for help.

India decided to assist, but only if he agreed to become part of India.

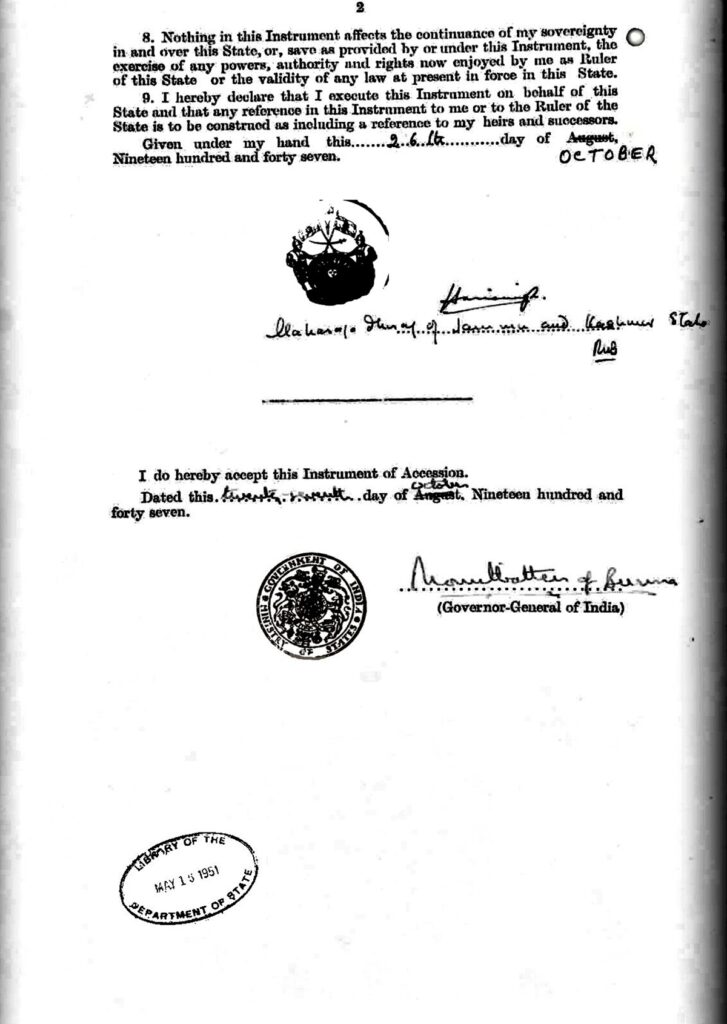

Thus, on 26 October 1947, Maharaja Hari Singh signed the Instrument of Accession and joined India.

The second, signatory, page of the Kingdom of Kashmir accession to Dominion of India document, from the State Department library

Both Pakistan and India would lay claim to Jammu and Kashmir and would fight a war over the region until 5 January 1949, leaving the region’s fate unresolved, with two thirds being occupied by India and one third occupied by Pakistan.

Indian soldiers in the field in 1947

Relations between Indian and Pakistani would never recover from this dispute, and remain hostile. The two countries fought two territorial wars, in 1965 and 1971, and have been involved in numerous clashes since.

After his kingdom was absorbed into India, Hari Singh was exiled from it and lived the rest of his life in Mumbai. His ashes were returned to Kashmir upon his death.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend