This piece was first published in January.

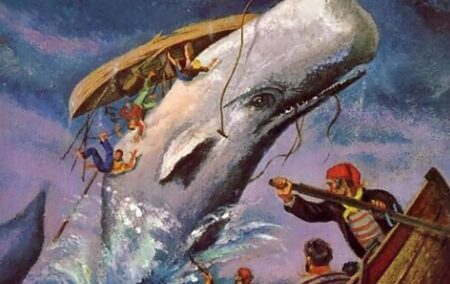

It’s doubtful that more than just a few South Africans, including those with a fondness for literature, will ever read Herman Melville’s magisterial novel Moby Dick.

This is a shame, not only because it is one of the most renowned pieces of literary work to be produced in English and is referenced frequently in all manner of art and media – for example, in Oliver Stone’s 1986 war movie Platoon, and in the name of the coffee franchise Starbucks – but because it is a deeply thoughtful and insightful piece of literature, bringing together complex themes about the place of the self in the world, alienation, obsession, solidarity and truth. It’s a work that readers can learn and grow from.

The portrayal of Captain Ahab is central to the novel. Described by one writer as ‘a brilliant personification of the very essence of fanaticism’, Ahab is a stern, hardy whaling man well regarded by his crew and peers, but also marred by an aura of brooding, doom and fatalism. Driven by a rage against Moby Dick – the White Whale that had taken his leg – he turns the voyage from a commercial venture into an instrument of his personal revenge.

When confronted by his first mate about the incongruity of this – abandoning the harvesting of valuable whale oil to kill a ‘dumb brute’ – Ahab retorts, striking his breast: ‘If money’s to be the measurer, man, and the accountants have computed their great counting-house the globe, by girdling it with guineas, one to every three parts of an inch; then, let me tell thee, that my vengeance will fetch a great premium here!”’

In the final climactic confrontation, Moby Dick stoves the ship; and with the exception of the narrator, Ishmael – who survives ironically by clinging to a watertight coffin – the entire crew follows Ahab to their deaths.

A report emerges…

On 18 January, the SA Human Rights Commission released a report into what for a few days in early 2019 was the story that held much of South Africa in rapt attention: a case of racism, captured on camera. Not only racism, not only with pictorial evidence, but racism perpetrated against small children. Not only against small children, but by a teacher to whose care they had been entrusted. Add to that a few other signifiers – an Afrikaans language school in a platteland town – and it’s hard to imagine a better template for outrage.

The issue was a photograph of a Grade R class at Laerskool Schweizer-Reneke, apparently segregated by race. A small group of black children sat at one cluster of tables, while a larger group of white children sat at another.

For the most part, it’s safe to say that this had long been forgotten. South Africans express their indignation in short, intense, and sometimes fanatical bursts, but rare are those cases that remain in the public mind after the initial excitement has dissipated. And as this report details a controversy that took place four years ago – a remarkable lapse of time, it seems – it has not attracted much attention, and certainly not a great deal of passion.

For those who had followed the case beyond the opening apoplexies, there is actually not much that would be new. In fact, the teacher who had been fingered as responsible and suspended, Elana Barkhuizen, had already been cleared by the Labour Court – in January 2019.

It’s worth setting out in brief what took place. When the offending photo went public (it’s not entirely clear how this happened), indignant and impassioned action by political parties and ‘community members’ followed. This included crowds entering the school premises to protest, sometimes aggressively and violently.

The provincial MEC for Education, Sello Lehari, turned up and addressed the aggrieved ‘community members’. At this time, he announced that the reprobate teacher, one ‘Ellen Barkhuizen’, would be suspended.

The MEC failed to get Barkhuizen’s name right, but this was par for the course. The public narrative had twisted just about everything. In fact, Barkhuizen – Elana Barkhuizen – had taken the photo, but was not the teacher responsible for the class it depicted, nor for the seating arrangements.

The class teacher, Elsabe Olivier, had seated the children in this way as a temporary measure to assist them in adjusting to the new environment. The criterion was not race, but linguistic background (about which more below). Besides, as the SAHRC report points out, the ‘impugned’ photograph was taken at 9:12:21am. Another – which showed black and white children sitting together – was taken at 9:18:06am. In other words, the seating changed within six minutes of the offending photo having been taken.

To be sure, there was some consternation on the part of some parents when they viewed what looked, superficially, like segregation. This was reported in the media at the time – TimesLive carried a report entitled Parents fume as black and white grade R children are ‘separated’ in North West classroom. However, the SAHRC report records that an unhappy parent queried the matter and ultimately accepted the explanation.

Indeed, it seems that the ‘fuming’ had less to do with parents whose children were actually involved in these events than by the amorphous ‘community’ who chose to be outraged on their behalf. For Barkhuizen and her family, fear of violent reprisals sent them into hiding, and she told Maroela Media that they had seriously contemplated emigration.

Barkhuizen had done nothing wrong. She was peripherally involved in the matters that served as the spark (or the pretext) for the storm. She won her case in the Labour Court and was reinstated. The SAHRC report was a pretty comprehensive vindication. Not only did it find that ‘the allegation that the school unfairly discriminated against the four learners is not substantiated’, but it condemned the conduct of the MEC towards her. ‘The public disclosure of Ms Barkhuizen’s name by the MEC constituted a violation of her right to privacy and prejudiced her human rights, including her rights to due process, security, freedom of movement, association and human dignity,’ the report found. He (the MEC) was directed to issue a public apology.

As for the outraged activists and ‘community members’, the report had sharp words. The storming of the school had violated the rights of the schoolchildren to their education. And the dissemination of the photograph had exposed the children’s identities, violating their right to privacy. There is more than a dose of irony in all this: those who claimed to be concerned for the wellbeing of the children were most directly responsible for doing them harm. There is something in this worthy of Herman Melville, calling to mind perhaps the image of Ishmael desperately clinging to a coffin to preserve his life.

Chasing the Whale

All this calls to mind Moby Dick. South African society has been wounded by a racist legacy, though not destroyed by it. The perennial question is how it chooses to respond when it is confronted with reminders of that past or with manifestations of those pathologies. The Schweizer-Reneke affair showed the Ahab impulse.

It is a blind fanaticism that seeks out its own White Whale in the form of racism. Like Ahab, it is willing to risk a great deal – even to the point of endangering life – to visit vengeance upon it. And like Ahab, the premium to be earned is often less in the goal for which the activists and ‘community members’ are nominally striving than in their own hearts and senses of accomplishment. ‘Fighting racism’ often comes across not as striving for a better society, but as punishment of the transgressor, in this case the imagined transgressor, and the vindication of the activists’ worldview.

It certainly was in this instance. With scant care taken to assess the claims being made or to ascertain their validity, anger was unconscionably turned on a woman who had as good as nothing to do with the circumstances that had driven the outrage. The children involved were shamefully left as collateral damage. Those who shared photographs of the children to advertise their outrage (and their virtue) should ask themselves just what the price of their goodness was.

Indeed, perhaps there is something beyond Ahab in all this. He at least had directed his rage at a specific target. Moby Dick, dumb brute though he may have been, had taken Ahab’s leg. In this case, one wonders whether getting the ‘right’ racist mattered, or whether anyone would do. There are certainly cases where that hardly seems to be a point of great concern.

Perhaps more corrosively, the drive to excise racism – with an eye firmly on South Africa’s past – is gnawing at the very idea of human rights in the present. Here, the SAHRC has been complicit, declaring that racist and hate-based abuses are judged according to the identities of the perpetrator and victim. It is the SAHRC’s position, former Deputy Chair the late Priscilla Jana said, deliberately to be more lenient on black offenders in race cases than on white ones because of ‘historical context’. A one-time legal officer at the commission, Shanelle van der Berg, made similar remarks.

It’s a distressingly small step from saying that the consequences of abuse should differ owing to the respective identities of the victims and perpetrators, and contending that the enjoyment of rights should similarly be so dependent. It’s difficult to see the very idea of human rights enduring under those assumptions. Beware of the Ahab impulse!

Against this background, incidentally, it’s quite remarkable that the report ultimately came out on Barkhuizen’s side. Although, as Dirk Hermann of the Solidarity movement commented (translated loosely from Afrikaans): ‘The South African Human Rights Commission also investigated the case. Four years later, their report has come out. In the report you can see that they really made an effort to get something against her. They couldn’t. She is just a good teacher who went through hell because of racist politicians.’ Sadly, one can’t help agreeing. The SAHRC would probably have been far more within its comfort zone and ideological seascape had it been able to pin at least some racism on Barkhuizen and the school.

Meanwhile, as in the novel, the White Whale simply swims away. The narcotic exhilaration of a protest or an indignant Twitter mobbing or the pious declaration of the imperatives of ‘anti-racism’ does nothing to build consensus or coherence or mutual respect.

Starbuck

Yet in Moby Dick the character of Starbuck, the respectable, pragmatic New England seaman, provides a counterpoint to Ahab. It is he who voices misgivings about the pursuit of the White Whale, challenging Ahab: ‘I am game for his crooked jaw, and for the jaws of Death too, Captain Ahab, if it fairly comes in the way of the business we follow; but I came here to hunt whales, not my commander’s vengeance. How many barrels will thy vengeance yield thee even if thou gettest it, Captain Ahab? It will not fetch thee much in our Nantucket market.’

In these lines, Starbuck captures something profound. Why is the crew on the ship? What is the rational purpose of the voyage? Starbuck is no coward. He is willing to face death as an inevitable part of the work, but there is no sense in doing so to satisfy nothing greater than the angry desires of the captain. The fate of the crew is testimony to this.

So it is here. Brian Pottinger once noted that some interests in the country focused on racism not to resolve it, but to keep it aflame.

The reader can decide whether the assault on Barkhuizen did anything constructive to oppose racism – though it’s doubtful. More likely it fostered precisely the sort of resentment that provides an ecosystem within which racism can breed.

The approach exemplified by Starbuck would see racism as a challenge to be confronted, but to be undertaken with full cognisance of facts as they exist, not as they may be assumed or as some might find them expedient to be. It would seek to understand the specifics of a case before passing judgement and then have the courage to call out abuse or to announce – and do so happily (why the odd reluctance to celebrate good news around racial issues?) – that there is no problem at hand, or that the problem is not what it was assumed to be. Either option would require ‘being game for the crooked jaw’; they would, though, seek to do so for the profit of better relations among people.

The Labour Court judgment in the case commented: ‘Racism cannot and should not be tolerated, and it has to be attacked and destroyed wherever it is found. In the same breath, however, racism should not be found and named where it does not exist.’

In fact, there is an issue raised in the report that warrants some serious introspection. This is that the black children who had been placed together were not in fact all Setswana speaking (their presumed home language) and hence would not benefit from the language support provided; one child did not understand that language at all. Another of them was conversant in Afrikaans, and consequently should have been placed among the Afrikaans-speaking white children. So, it’s reasonable to conclude that an element of ‘profiling’ had taken place. Though there is nothing to indicate that this was malicious, it could and should have been handled better. The linguistic backgrounds of the children should have been properly noted, not assumed. So it should be: let this mistake be acknowledged and serve as a lesson for future improvement.

Ms Barkhuizen and the children involved in this matter are all specific, unique human beings. For those for whom this was simply a ‘cause’, Barkhuizen was probably no more than an avatar, the children just props in a grotesque morality play. The consequences they stood to suffer might have been (and might be) with them long after the moral outrage had found another outlet. South Africa would do well to bear this in mind. Vengeance does not mean justice.

Tragedy

Reading Moby Dick, particularly with a focus on the relationship between Ahab and Starbuck, one is struck by the thought that while Starbuck recognised more than anyone the disaster that awaited, in the end he folded before Ahab and accepted his leadership.

How often is this the way of things? Terrified of the censure of the mob, those of goodwill stand by as others endure injustice. Or even to make the obvious call for proper understanding before rushing to judgement.

Perhaps nothing is more tragic in this affair than that even after pretty much everything that has exonerated Barkhuizen and explained why this was a non-story became known, enough investment in the outrage lingered to keep it going.

South Africans are fond of pointing to adversities as ‘opportunities’ for learning and reflection. Perhaps this is one of them. It would be a tragedy indeed if nothing is learned. Though that may be the South African tragedy.

[Image: https://www.historyhit.com/culture/american-publication-moby-dick/]

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend