The Myers-Briggs personality type indicator remains a popular management tool in South Africa and around the world, but it’s bunkum.

Apply for a job or a promotion in many corporate settings, and you may well be expected to subject yourself to a personality evaluation. The most popular and enduring of these tests is known as the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI).

This is the test that purports to produce a four-letter summary of your psyche, and puts you neatly in one of 16 pigeonholes.

Each letter categorises you on a binary scale. You get an E for extroversion, or an I for introversion; an S for sensing, or an N for intuition; a T for thinking, or an F for feeling; a J for judging, or a P for perceiving.

The first three of these dichotomies are derived, roughly speaking, from the personality typology established by the founder of analytical psychology, Carl Jung, and his name is often invoked to legitimise the MBTI.

While Jung’s typology claimed to identify eight personality types, the MBTI’s two options across four indicators results in a 16-fold classification of personality.

You’ll find these four-letter signifiers on curricula vitae, social media descriptions, LinkedIn biographies, and dating profiles.

Popularity

Many people, companies, and even some academics take the MBTI quite seriously, and consider it a valuable tool to determine what sort of job a person might be suitable for and how they are likely to fit into a team (if at all). Less formally, people use them in the belief that they shed light on compatibility in relationships.

Consultants and self-appointed business experts promote the MBTI for use in recruitment, personnel management and people development.

Academic papers explain that if MBTI testing doesn’t work for you, you just need better training. Others elucidate type distribution patterns, examine the reliability of the MBTI for psychometric testing, or claim to validate the MBTI in the South African context.

The popularity of the MBTI cannot be doubted. Two and a half million people take an MBTI test every year, and 89 of the Fortune 100 companies report using it.

The Myers-Briggs Company says it is trusted by organisations including Cornell University, Ford, Mondeléz International, Microsoft, the US Army and the British National Health Service.

It all sounds very legit, but it isn’t.

Positive affirmation

The MBTI is corporate astrology. It is woo. It is pseudo-science. It is bunkum.

It cannot tell you much that is useful about people’s personalities, or how they are likely to behave in particular situations. It has no predictive power, and no explanatory power, either.

Every MBTI personality type is a delightfully positive affirmation.

Not a negative personality trait in view. One might be delighted to be labelled with any of these 16 supposed personality types, since they all sound wholesome.

I did a free online version of the test (because a real MBTI test would cost me $60), and was shifted from J to P because I admitted to being bad with deadlines. They called me “flexible”. Wonderful!

You’ll notice that the opposite of the positive traits which are lacking in other types are never included. None of the types is described as “insensitive” or “untrustworthy” or “lacks common sense” or “unfriendly” or “incurious” or “irresponsible”.

That’s far from the only problem with Myers-Briggs.

Bell curve

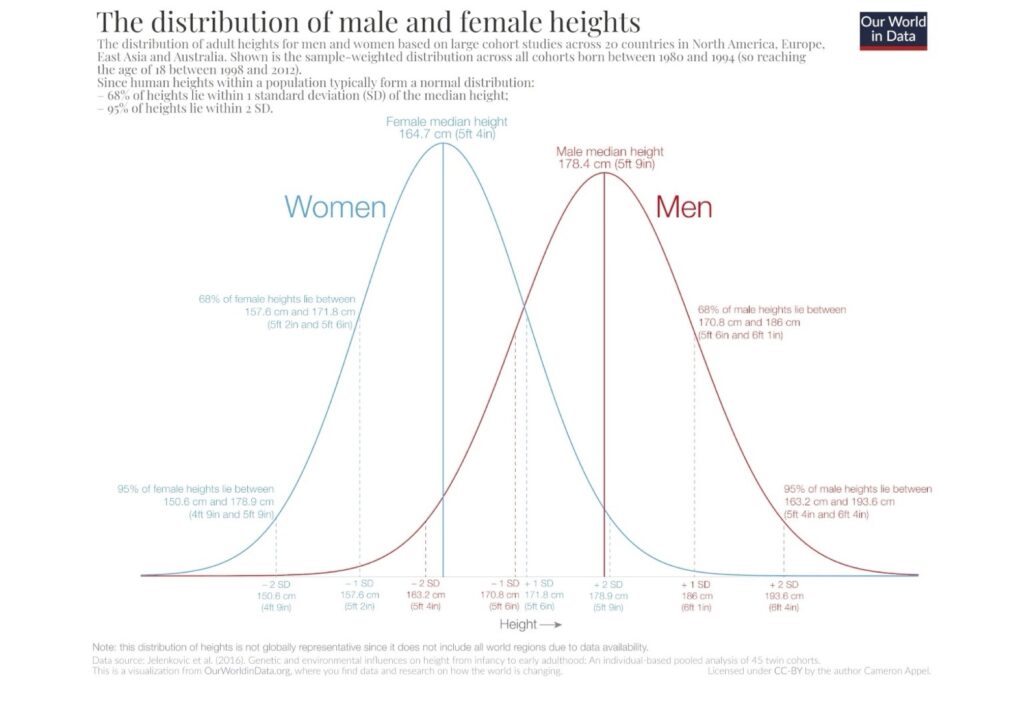

It is a pretty fundamental observation in psychology and medicine that many characteristics of people can be described by a normal distribution, or bell curve.

Most people fall near the middle of the bell curve. Few people are outliers in either direction.

The personality qualities that the MBTI tries to measure are no different. Most people are neither very introverted, nor very extroverted, for example. Most people do not make decisions exclusively on the basis of rational thought, or exclusively on emotive feeling, but would fall somewhere in the middle.

Worse, research shows that people who are good thinkers – that is, they exhibit a high cognitive intelligence – are more likely to also better understand and manage emotions and feelings – commonly described as emotional intelligence.

The T versus F dichotomy of the MBTI is, therefore, based on a false premise. There is no such dichotomy. A similar argument can be made about sensing versus intuition. The supposed opposites of the MBTI types are not opposites at all.

Another problem with the MBTI’s binary divisions of what are more like bell curves or overlapping non-independent traits is that it splits people in a misleading way.

There is likely to be a much smaller difference between two people who find themselves near but on opposite sides of the mean, than between such a person and someone who falls on the extreme of the same side. Yet similar people, near the mean, will get opposite labels, while widely different people on the same side of the mean will get the same label.

The answers to the test can, even when taken by the same person, be influenced by mood, or context. One could be extroverted among friends and family, but introverted among strangers. Conversely, an intensely introverted person could behave like an extrovert when put on a stage in front of an audience.

Binary creatures

Humans are not binary creatures. People’s personality traits fall on a spectrum, and where they fall on the spectrum is not necessarily constant or predictable.

Jung recognised this, and did not consider his type preferences as dualistic, but one assumes Briggs and Myers didn’t read that far into his book.

One might be meticulous and careful in planning a budget, but flexible and tolerant in managing people. One might have good common sense, except when the subject is a matter of political partisanship. One might handle pressure calmly, except when things aren’t going well at home. One might get on with others, except when one is hungry and irritable. One might be a good team player, except when one has a professional rivalry with the team leader. One might be perfectly fine with deadlines for certain kinds of jobs, but not reliably so for others.

A test that does not consistently give the same results, and can depend on mood and context, isn’t a test worth basing business decisions upon.

The results are also easy to manipulate. It doesn’t take a genius to figure out what the questions are driving at, and to give employers the answers you think they’ll be looking for. Good with deadlines? Of course I am!

All of this means that the MBTI personality type is not at all predictive of aptitude or suitability for any given job or social relationship.

Designed to be sold

The Briggs Myers Type Indicator Handbook was published in 1944 by Katharine Cook Briggs and her daughter Isabel Briggs-Myers.

They were not psychologists. They were not psychiatrists. Both Briggs and Briggs-Myers were home-schooled. Briggs obtained a degree in agriculture, before becoming a teacher. Briggs-Myers was a critically unacclaimed fiction writer with a political science degree.

Besides having read Carl Jung’s Personality Types (which itself was influenced by the four ancient elements of earth, wind, water and fire) nothing qualified either Briggs or Myers to design a psychometric testing framework.

They were, to use a technical term of psychology, clueless.

The MBTI has undergone many revisions, and has metastasised into a very profitable business. Its personality types are all positive and affirmatory because the test is designed to be sold.

The MBTI and related tests are maintained by the Myers & Briggs Foundation, These tests may only be administered by consultants who are certified by the Myers & Briggs Foundation or The Myers-Briggs Company.

Although the MBTI seems like a simple inventory-style assessment that anyone with superficial familiarity with psychology could administer, the company charges $3 000 for certification to make sure that only true disciples peddle the MBTI.

Companies then employ these certified consultants, and pay The Myers Briggs Company about $100 per person they would like to test.

Companies really ought to stop paying for these stupid tests, and their victims – people whose careers paths are influenced by their performance on MBTI tests – deserve better from their (prospective) employers.

The MBTI is not an academic exercise with a valid psychological basis. It is, in the words of various researchers, an “act of irresponsible armchair philosophy”, a “Jungian horoscope”, and a “party game”.

Like most charlatanry, it is a highly profitable business, but that doesn’t mean it isn’t corporate woo.

[Illustration: by Ivo Vegter (wordcloud.webp)]

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend.