Returning to normality, or at least the world beyond social media and politics after sustained immersion, is not proving easy. It’s my fault. I made the mistake of seeking respite from these useful but often spirit-taxing worlds in a best-selling fiction novel.

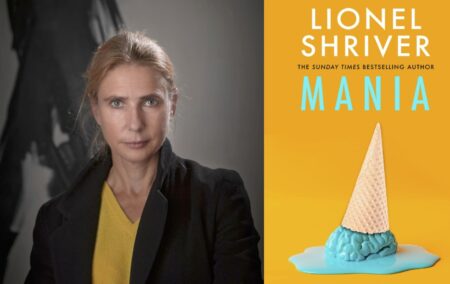

The problem was my choice of Lionel Shriver’s latest fiction novel, Mania. This was not ideal for the task of recovery from too many weeks of listening to what Douglas Murray, writing in The Spectator, has called the “uninformed ‘howling’ of social media in this ‘dark age’ of a ‘surfeit of information”.

As we all know now, or at least those who are not in denial within the African National Congress, this year’s national election was very different, even extraordinary.

The place to go, so as to keep up with all that followed over several weeks in June and into July, even if you are not a politics nerd but simply a “concerned citizen”, was on social media: primarily the breaking news platform X, live streams and, occasionally, broadcast news.

But extensive exposure to the moronic racism and hunting packs of both left and right spectrums on X is definitely harmful, and possibly even dangerous for one’s soul.

I thought an engaging book would be the antidote.

In the parking lot, the mall and the bookshop, I interacted with a variety of people who were polite, not racist, or angry, or apparently eager to push me into the sea and back to the island my people left for better lives 200 years ago.

This went some way to restoring my equilibrium. I emerged with Shriver’s latest iconoclastic work and settled down to continue the remainder of my cure.

In hindsight, I should perhaps have chosen something more along the escapist lines of my old favourite, Angelique and the King, a bodice-ripper which helped me survive many hours of boring school history classes.

This dependence on a book is very ‘boomer behaviour’, I know. But then I am a boomer and so is Shriver. She is, as I have no doubt told you, one of my favourite authors and journalists, as well as a wise woman who chooses to keep off social media.

Shriver is a dab hand (Note: for the benefit of any readers harbouring ill-will and sniffing for racism, this is an English slang expression but does not connote anything derogatory, as you should be able to deduce from the context) at skewering political correctness and exploring the logical consequences of societal trends and beliefs.

Mania is the story of a contrarian low-grade academic, her family and her best friend, in a fictional but all too recognisable modern world, in which the latest social justice imposition on society is the recognition of ‘cognitive equality’ or mental parity.

In this world, intellectual or skill meritocracy is heresy; knowing the correct vocabulary to use is essential to survival in your career; stupidity is deemed not to exist, only ‘alternative processing’; and to be clever or display any critical thinking capacity is dangerous.

Here one risks being shunned, even punished, for using the ‘D word’. No, not ‘dogs’, but ‘dumb’. Dolt, idiot, stupid…and any similar word or phrase found in a thesaurus and denoting a lesser intellectual ability are verboten.

When you’ve just come off a sustained period on social media, where many people could be pejoratively labeled in this way, the premise of this book hit home.

It’s also not a difficult stretch of the imagination, if one has one. Many clearly don’t, as the past weeks have shown me.

We’ve already grown accustomed to overly generous prize-giving at our children’s places of learning and to grade inflation, and DEI trumping skills and ability.

It’s also easy to imagine the ‘kind’, ‘justice-seeking’ impetus behind it.

After all, you shouldn’t go around being an intellectual elitist or ignoring the fact that people think differently. Should you? If equality and inclusiveness are the goals, why do we discriminate against those who are not intelligent or clever?

In Mania, contravention of the linguistic taboos around mental parity could provoke a social worker visit, or the end of your career.

Movies, television shows and books are condemned to the archives for their derogatory titles, themes or story lines, when deemed to refer to cognitive differences between people. Forrest Gump has been dumped off Netflix.

Things become unsayable, unless prefaced with some or other lengthy disclaimer that defends the correctness of society’s move to treat everyone as an intellectual equal and do away with any regard for innate ability or qualifications.

The Mental Parity Movement’s success makes undergoing even relatively minor surgery a dangerous venture. What if the HR team of your hospital no longer screens surgeon applicants in any way?

Shriver has a penchant for writing about parallel worlds that follow nascent trends in our own world or our own alternative life choices to their logical conclusions.

At the core of the novel is a debate over principle and personality. Does one toe the line, “go along to get along”, or resist?

A couple of years ago, Shriver told an interviewer that her outspoken political opinions had made her lose friends. It’s something that has happened to many people in these days of extreme partisanship and identity politics.

Which brings me back to my little quest for normality.

I can’t say, as John Cleese does in his testimonial on Mania’s front cover, that the book made me laugh out loud. Shriver’s satire had comic moments but mostly it frightened me by highlighting the consequences for ordinary people in societies that seesaw from one extreme to another, demanding obeisance to concepts that do not necessarily accord with facts.

I understand desirable normality to be something other than adherence to custom and the majority view or zeitgeist. I choose to regard it as something more like the elusive political centre, to which some are hoping our GNU will eventually take us, one day, in the next few years, or decade.

For me it’s the average, the median, the moderate, sitting at the top of the bell jar curve. Terence Corrigan has written in BizNews that the IRR’s polling, over time, has shown that “the weight of South African opinion is broadly restrained, pragmatic, moderate; materialist in aspiration and respectful of the claims of fellow citizens.”

That’s what I regard as normal.

Shriver, however, has made me wonder how well we, the normal people, can or will withstand or counter the many waves of social as well as political extremist belief, currently rolling across the Western world and through our own immediate society, demanding compliance despite their patent nonsensicality. Or is the word I’m searching for ‘idiocy’?

P.S. I will continue working on my restoration to as normal a state of mind as is possible, with a holiday in the South African bush. It’s been successful in the past.

[Photo: Essex Book Festival]

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend.