The recent controversies over “racism” at Pretoria High School for Girls and Chidimma Adetshina’s participation in Miss South Africa reveal an illness in South African society: politicisation.

But the whole world now suffers from it to varying degrees. It is high time not merely for an “anti-left” or “anti-right” politics to be embraced, but an anti-politics per se.

The only good thing about politics is what it is in theory: a way for groups to come together to solve collective problems. But this does not intuitively describe how most people experience politics in reality.

Frédéric Bastiat’s essay, The State, comes closer to a more apt definition of politics, and one that has not been bettered since 1848. Granted, Bastiat was defining the state itself, but I think this best describes the whole domain of politics:

“The state is the great fictitious entity by which everyone seeks to live at the expense of everyone else.”

Politics is about rentseeking, offloading responsibility, and imposing one’s preferences using a coercive third-party called government. “Solving collective problems” is not it, not least because it has been shown conclusively that the market economy and civil society are perfectly capable of solving collective problems comfortably outside of the political realm.

Liberalism stands fundamentally opposed to politics. It seeks to eliminate where possible, and minimise where appropriate, the political realm.

Rotting society

The Miss South Africa pageant debacle is illustrative. Here is a private company, using its own money, deciding upon entry criteria for its own private competition. Nothing this company does affects, in the slightest, the lives, the liberty, or the property – merely the curiosity – of anyone who is not directly and consensually involved in the company’s affairs. The company is a fully responsible entity that does not rentseek.

On the other side, you have a society that is falling apart under the weight of record-shattering violent crime and unemployment. It has repeatedly elected a hopelessly corrupt cadre of even more hopelessly (if that is possible) inept and incompetent politicians. And now it insists that this private company disqualify and report to the authorities someone who has a “Nigerian-looking name”.

A prominent ActionSA member even insisted online that Adetshina be arrested for her mother’s alleged misdeeds.

There is, of course, something fundamentally toxic about the idea that “the public” (represented by their chosen representatives on Twitter) should be able to tell a private company, like Miss South Africa, who it should and should not allow into its competition. The public is doing harm to an institution that has harmed no one.

This is social rot. This is a society that is ill. This is a society whose continued suffering begins to make more and more sense every passing day.

Miss South Africa is entertainment. Models are entertainers. The pageant is about models and their target market having mindless, harmless fun.

Yet, if you asked South Africans, you would have sworn that this pageant is about appointing South Africa’s next ambassador to the United Nations. The winner of the pageant represents “us” and therefore “we” have an overriding say – a veto – on who wins: on who wins this private pageant, established and funded privately, at the initiative of a private company.

Like spoiled children, South Africans redefined “the public interest” − a sacred legal notion that controls how public authorities are meant to behave, to the benefit of the tax-paying public – as “the public curiosity”. Anything the public happens to “be interested in” becomes a matter of democratic decision-making. Effectively, this is unhinged totalitarianism.

The Pretoria High School for Girls debacle is little different. A squabble between mostly underaged pupils, which was meant to be dealt with – as it has been for centuries – by parents and teachers, was turned into a public spectacle that threatened the futures of each of the involved learners.

This did not happen by accident. The South African public demanded that it be so. The South African public politicised this intimate, private event.

Res publica

There is something noble and romantic about the idea of a res publica (literally, “a public thing” – the source of the word “republic”): the community gathers, hyper-aware of their responsibilities towards one another, to solve some issue of common concern or advance some common cause.

But what we have discovered – and what liberalism, at least for now, stands alone as the solution to – is that the unlimited extension of res publica, where anything and everything becomes “a public thing,” is rotting our civilisation.

Conservatives enjoy blaming (so-called) “liberals” and the left for modern social rot, particularly in the West. While it is very true that more accurately so-called progressives and the broad left have contributed immensely to the decline of Western civilisation, the res publica that they have used to do so, is itself a fundamentally conservative notion.

That is why, to conservatives, it is incorrect to say – for example – that homosexuality is a purely private matter. It has spillover effects for public morality, they say, and sexuality is therefore a res publica.

Whereas liberals would solve the problem of drunk vagrants sleeping on park benches by privatising the park and leaving that determination to the owner, conservatives would deem the park a res publica, and instead try to use overwhelming state violence to solve the issue.

The same ultimately goes for prostitution, drug use, and even subsidising the arts or agriculture, and any manner of things that are obviously private phenomena that conservatives deem to be, in some way, in the public interest.

This kind of conceptually unlimited reasoning was always going to end up helping the anti-Western left. Not only is sexuality a res publica to the left, too, but they have flipped the conservative approach around; when it comes to homosexuality, the public – including the arts, schools, and so forth – must actively celebrate and morally endorse anything “queer”.

Public parks, of course, would also not be privatised by the left. They, too, regard these as res publica: but instead of using state violence to solve the alcohol abuse problem, the left creates a very public culture of guilt-tripping and even “cancelling” anyone who seeks to do anything about disorder. If you want to address disorder, you are a racist, a sexist, an ableist, and so forth.

The conservative res publica has been weaponised by the left not merely against liberty – something many conservatives would endorse – but against the very conservative foundations of the res publica notion itself.

Be anti-political, not apolitical

Only liberalism – real, classical liberalism – is the cure for this kind of rot.

It draws a bright line between the public (that is, the governmental – what relates to the lawful invocation of coercive force) and the private (everything else). Everything deemed “communal” – of which, undoubtedly, much of human society is based on – remains private and subject to the private imperatives of individual consent and agreement.

Liberalism’s anti-politics has been construed as an attempt to isolate and atomise individuals from their broader community contexts. This is a misconstruction.

Liberalism’s anti-politics is, instead, a response to the creeping, conceptually unlimited extension of political – and, nowadays, usually democratic – principles in totalitarian fashion into all facets of human existence.

In fact, liberalism’s anti-politics is probably the best hope that particular communities have to retain some autonomy over the things that concern them, before bigger (and bigger, and bigger) self-defined “communities” subsume them into their own res publica.

Many people have concluded that the best way to shield themselves from this degeneracy of politics is to become apolitical. But this is not the appropriate response.

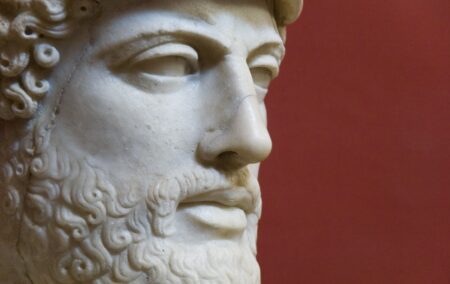

In many ways, being apolitical is counterproductive, and potentially allows politics to seep into even more areas of our lives. You do not disappear from the political realm simply because you do not engage with it. As Pericles is said to have remarked, “Just because you do not take an interest in politics does not mean politics will not take an interest in you.”

One must, rather than being apolitical, be actively and consciously anti-political. This means being very engaged in the political and public affairs of one’s society – or supporting those who are, in some substantive way – but with the clear purpose of bringing it to an end.

Put another way, the best way to deal with a band of robbers constantly harassing your town is not to act as if they do not exist, but to engage them head-on so as to eliminate the threat.

[Image: https://www.flickr.com/photos/pescudero/4692659189]

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend