The appointment of Roman Cabanac as chief of staff by the Minister of Agriculture, John Steenhuisen, has triggered a great deal of commentary in the media, most of it negative and much of it tendentious.

As is customary, the story dominated the headlines for a while, then died away as public attention moved on to other things.

What are we to make of the appointment and the public reaction to it?

The reaction was certainly not unexpected. Both Steenhuisen and Cabanac will have known what was coming. Cabanac built a successful podcast and YouTube channel by carving out a space for himself as a veritable enfant terrible of news commentary, never shying away from provocative takes on South Africa’s culture and politics.

Causing offence was never a reason for not saying something and at times Cabanac seemed to positively delight in it. His statements were often edgy, designed to provoke a response, even at the price of causing irritation and annoyance. It was a conscious departure from the conventions of polite discourse, aimed at building a reputation for challenging traditional assumptions and conventional wisdom.

A senior member of a prominent South African think tank whom I met last week expressed his dislike of Cabanac based on some online interactions he had had with him. But that hardly marks out my interlocutor as unique. While his abrasive approach gained Cabanac the admiration of those who respected him for sticking it to the man, it also meant he made a lot of enemies. Many of those now attacking him are relishing the opportunity for some payback.

Here, I must add a disclaimer: I know Roman Cabanac personally, have encountered him to be thoughtful and considerate albeit delighting in provocation, and have had many friendly conversations with him. Where we disagreed – which was often – he was unfailingly respectful and courteous.

Backlash

But Cabanac’s former positioning and media profile meant a media backlash was predictable. If so, why did Steenhuisen consider Cabanac for the position, and why did Cabanac accept? The cost was known (and has become evident), but what about the benefit that has to be considered as part of the trade-off?

The first thing that stands out, contrary to what many commentators have claimed, is that this is not an example of cadre deployment. Cabanac does not look back on a distinguished track record of many years as a loyal DA cadre. In fact, he has been vocal in his criticism of the DA – and, I suspect, of Steenhuisen himself. Five years ago, he was the co-founder of a political party that ran in direct opposition to the DA when he helped create a political competitor in the form of the short-lived South African Capitalist Party during the 2019 elections.

In other words, Steenhuisen chose to appoint someone who has been vocally critical of the DA in the past, an outsider rather than a party insider (although Cabanac ended up endorsing the DA just before the 29 May elections). This was a counterintuitive choice. It speaks to a streak of unconventionality which probably reflects a sense that the department of agriculture (like many other ministries) needed a shake-up. It needed to be exposed to someone willing to challenge the status quo and question unspoken assumptions. That is certainly a bill which Cabanac fits. SA has a growth and unemployment problem and the government needs unconventional thinkers – preferably ones who believe in the power of free enterprise − to help solve them.

Walked the talk

The next point is that Cabanac has often argued in his podcasts that people should stay in South Africa and get involved to make it successful. He has walked the talk: my understanding is that he went into government because he thinks it is the right thing to do and because he wants to make South Africa a success, something he made explicit in a statement released yesterday: “When the chance came, I took it, driven by a genuine desire to help build a better future for all South Africans”.

Notably, he made the decision to do so even though he must have been aware that it came at a cost. It exposed him to the storm of criticism which he has now experienced, as well as accusations of hypocrisy for having opted to go into state service as someone who has been a vocal state sceptic. Anybody who goes into government and exposes himself in this way deserves respect.

Cabanac has also proved himself able to deliver. He is a serial entrepreneur who, unlike many of his critics, has co-founded successful business ventures in the form of the Renegade Report and Morning Shot podcasts. Steenhuisen will have made it clear that Cabanac’s role is to be effective in his department. He needs a chief of staff who is action-oriented and can get things done. Cabanac’s track record suggests that he can deliver, but he will have to prove it by the results he produces.

Amidst the arguments in favour of the appointment, however, there are some reasons to be critical of Cabanac’s appointment from a liberal perspective, which IRR Fellow Gabriel Crouse elucidated in a piece published on News24.

Some of Cabanac’s statements in the past expressed racial generalisations, a favouring of (ethnic) enclaves like Orania, and support for secessionism and authoritarianism that sits uneasily with the values of a through-and-through constitutionalist, non-racial, all-of-South-Africa, liberal party such as the DA.

Looks different now

Perhaps Cabanac’s views on the appeal of retreating into enclave-like laagers and seceding provinces were connected to the seemingly unstoppable downward spiral of South Africa prior to the elections, a picture which looks different now, as Cabanac acknowledged in his statement yesterday: “In 2024, both our country and I changed […] I am committed to working with anyone who shares the goal of a prosperous, united South Africa.”

Nonetheless, the statements Crouse highlighted above were disquieting and not insignificant. Perhaps the way to deal with them – in the absence of an authentic change of position, a possibility that should not be dismissed out of hand – is to do what the ANC and the DA are doing in negotiating some of the seemingly insurmountable ideological disagreements in the Government of National Unity: focus on producing results while prioritising incrementalism, common ground and pragmatism rather than aiming for outright confrontation and forcing the resolution of binary points of contention.

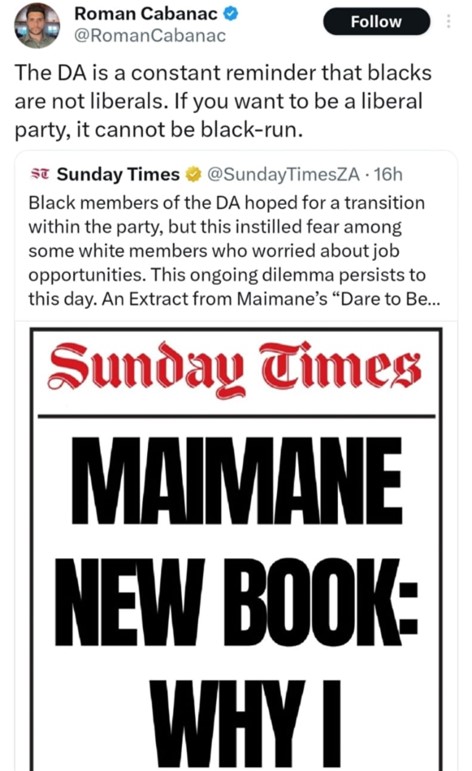

In this context, it is worth pointing out that some comments that Cabanac was excoriated for, like saying (with reference to the DA), “if you want to be a liberal party, it cannot be black run”, sound eerily similar to what much of South Africa’s commentariat has been saying for years.

For instance, the Daily Maverick a year ago: “With Steenhuisen and Zille at the top, the DA is unlikely to ever be electorally appealing to anyone other than a small fraction of the population in South Africa.”

Or the Mail & Guardian, 2015: “The problem with the DA is that it needs an excellent black leader.”

Or News24, in 2018: “It cannot be fine that the top leadership remains white […] when the party’s growth lies in the black community”.

It should not be controversial to point out that many South African journalists commonly make sweeping statements about race, thereby normalising racism, as the examples above illustrate. If Cabanac had said something like “whites are broadly racist and should not lead political parties in majority black countries”, many left-wing commentators would have presumably applauded him and endorsed the sentiment. That said, Cabanac’s tweeted comment on the publication of Maimane’s book ticks several of the boxes of self-criticism in his statement yesterday – it was simplistic, divisive, and insensitive (one might add: inaccurate) for Cabanac to imply that Maimane’s race was the reason he and the DA parted ways in 2019.

Inappropriate

Such sweeping racial generalisations – even more so race-based personal attacks – are something classical liberals like Gabriel Crouse are justified in calling out, whether they come from the left or from the right. There has been pressure for the Institute to distance itself from Crouse’s remarks; but that would be inappropriate.

The armchair critics who have referred to IRR writers as “orcs” and “snakes” for daring to criticise Cabanac will be ignored. Crouse’s comments have been entirely within the ambit of the IRR’s position, he is perfectly free to say what he thinks, and those who disagree with him are welcome to address the flaws they see in his piece, including of course here on the Daily Friend.

There is another point of difference that is important to address, and which reflects an important debate liberals need to have.

As classical liberals, we face criticism from “post-liberals”, a label that Cabanac might accept as applying to himself. Post-liberals hold that liberals have been naïve; they have allowed their tolerance to be used against them to undermine the very values that made them successful. To name some examples, the view of post-liberals is that freedom of speech is used to turn institutions against liberal ideals (like non-racialism); that favouring free trade is a mistake because it makes you hand trade advantages and technology to your adversaries; that focusing on individuals rather than collectives is misguided because it is collectives that hold and exercise power.

In this worldview, the freedoms prioritised under the liberal order are under threat from people who take advantage of its own provisions to break it down. The vision of the post-liberals represents a robust response to that challenge, one that is focused on power and how to wield it, on collectives and how to organise them, and on steadfast opposition against those who seek to impose restrictions on freedom of speech and the freedom to trade.

Paradox of tolerance

Theirs is a response to Popper’s paradox of tolerance: “Unlimited tolerance must lead to the disappearance of tolerance. If we extend unlimited tolerance even to those who are intolerant, if we are not prepared to defend a tolerant society against the onslaught of the intolerant, then the tolerant will be destroyed, and tolerance with them.”

The Institute’s classical liberalism is a tolerant one. It focuses on the individual and on freedom as expressed in free trade, free enterprise, and free speech, for example. Liberals must pursue these ideals, which the post-liberals believe are under threat from the intolerant left.

Within that context, we can recognise that Roman Cabanac is at odds with us in proposing a far harsher stance in countering intolerance than classical liberals typically adopt. But he does raise arguments about threats to freedom that we as liberals cannot ignore, and he does so not out of a sense of animus, but because he is worried that the liberal order is at risk of being taken over.

This is a risk the DA should be mindful of, too, as it considers what contributions unusual recruits like Cabanac can make in averting it.

[Image: https://morningshot.co.za/2021/04/19/5-reasons-why-i-write/]

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend