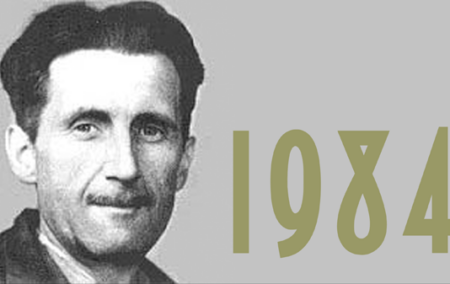

Nineteen Eighty-Four is one of the most influential books written in the 20th century. George Orwell’s tale of a man, Winston Smith, fighting against a totalitarian regime in a nightmarish and dystopic London, has captured imaginations for decades. It has been filmed many times and has been the inspiration for a number of subsequent movies, novels, and comic books, and even television reality shows.

For those not familiar with the world of Nineteen Eighty-Four, Orwell imagined a world divided into three totalitarian superstates –, Oceania, Eastasia, and Eurasia. Britain (now renamed Airstrip One) is part of Oceania, and is governed by the ideology of “English socialism,” known as Ingsoc. It follows Smith, a low-level functionary in the Oceanian state, as he starts to rebel against the constant oppression and surveillance. Orwell, who died in 1950, no doubt based his imagined countries on the real-life nightmare states of Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union.

Words and phrases such as “thought police,” “Big Brother,” “thought crime,” and “doublethink” are all now part of the English lexicon. Even Orwell’s surname has become an adjective – Orwellian has come to describe situations which are destructive to freedom and open thought, such as government surveillance or propaganda.

Disappointed

One wonders what Orwell (born Eric Arthur Blair) would have made of the world today. No doubt he would have been disappointed with the failures of democratic socialism (the ideology which he most identified with) and with the decline in the importance of newspapers. He would also likely have recoiled at technologies such as Facebook, which show intimate details of people, or demonstrate how people – especially in academia – are often cowed from speaking what they believe to be the truth because of societal pressure. However, he would have been buoyed by the fact that fascism and Stalinism have generally been beaten, and by the rise of welfare states in most of the West, and by the way free information is available to people across the world.

With regard to South Africa, he would have been pleased to see the end of racial discrimination – he was a person who abhorred bigotry. But he would no doubt have been appalled by the large numbers of poor South Africans and the terrible conditions many people in this country live in.

But what would also have appalled him would have been South Africa’s move to embrace “Newspeak” – one of the key concepts in the nightmarish superstate of Oceania in Nineteen Eighty-Four.

In the book, ‘Newspeak’ is a new language being developed by the apparatchiks of the Ingsoc regime to replace standard English. It is being developed so that concepts such as freedom cannot even be articulated, making the population easier to control.

An Oceanian lexicographer, Syme, tells Smith the protagonist that the classics of English literature will be translated into Newspeak and that “they’ll exist only in Newspeak versions, not merely changed into something different, but actually contradictory of what they used to be”.

Contradictions

South African Newspeak is perhaps not as developed as the Oceanian version, but it certainly has elements of the contradictions common in the Orwellian invention. And it’s not a new phenomenon. Think back to the Extension of University Education Act which was passed by the apartheid government in 1959. It did not, in fact, extend university education, but made it more difficult for black, coloured, and Indian South Africans to access tertiary education.

But South African Newspeak is still with us today. Perhaps the most obvious concept in Mzansi Newspeak is that of “economic freedom”. This is a term well-known to all South Africans, and our fourth-biggest political party has made it part of their name.

But “economic freedom” in this conception of the term is anything but, and in fact, contradictory to the term freedom.

“Economic freedom” as conceived by the EFF and others would see the state in control of practically all economic activity. Regulations would be stifling, and companies, businesses, and entrepreneurs would not be free to participate in the economy as they saw fit. If an EFF government ever came to power the economy would be anything but free, and South Africans would be condemned to lives of penury.

Pretensions

One could argue that even the “Fighters” in the EFF’s name is a form of Newspeak. The only fighting they ever seem to do is in Parliament, when the party can get mileage out of TV footage of their MPs being forcibly removed after being disruptive. Even the EFF’s pretensions of being “revolutionary” are Newspeak, given its support for inherited privilege in the form of traditional leaders, or the way most of the party’s leaders have found themselves comfortably ensconced within South Africa’s political elite.

The broad alliance which the EFF has formed with the MK Party and a handful of others in Parliament, following the 29 May election, also uses Newspeak. This group of parties styles itself as the “Progressive Caucus”, but there is nothing particularly progressive about most of the parties in it, particularly MK.

MK wants to return to the days when Parliament reigned supreme and was not constrained by a Constitution – just the way it was during apartheid. It also wants to expropriate all land and put it under the custodianship of the state or traditional leaders, as well as do away with the NCOP and replace it with a South African version of the House of Lords. It is not clear what is progressive about strengthening those who have inherited their leadership positions.

President Cyril Ramaphosa has also been guilty of Newspeak. Following the formation of the Government of National Unity (GNU) earlier in the year Ramaphosa said that inclusive growth would be a priority for the new government. He said: “Inclusive growth must drive the redistribution of wealth and opportunity.” But can an economy be inclusive when it redistributes wealth rather than produces and grows wealth? More Newspeak?

South Africans need to push back against our homegrown version of Newspeak and make it clear that the EFF does not support true economic freedom, nor is there anything “progressive” about the Progressive Caucus.

While South African Newspeak is not at the nightmare level of Oceanian Newspeak imagined by Orwell, it is important to protect language and the meaning of words. We must push back against politicians who change the meanings of words and phrases for their own ends.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend

Image: Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:1984_and_photo_of_George_Orwell.png