So far in this series, I’ve looked at some broad enablers of investment and how South Africa’s performance has stacked up against its peers. South Africa’s record has been sub-par; until this is turned around, South Africa will fail to provide the wealth and employment opportunities on which societal wellbeing depends.

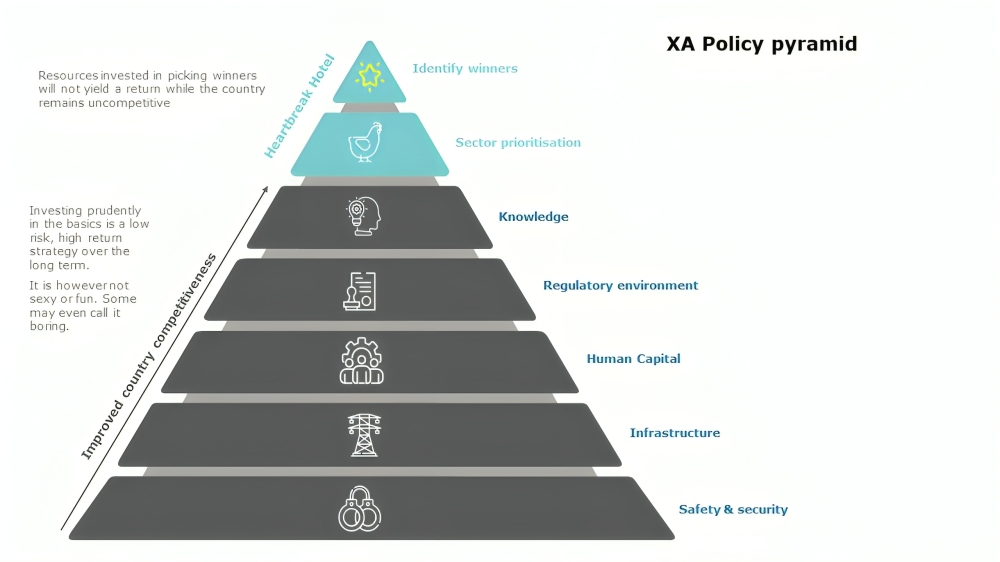

If South Africa is to turn this around, it needs to understand the nature of its deficiencies. To get a sense of these, I recommend a simple but illustrative schematic put together by XA Global Trade Advisors.

It is structured like a pyramid for good reason: it mirrors Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. In the case of the XA pyramid, the factors captured on the lower levels are more broadly critical for success (indeed, for societal existence), while those on the top represent bespoke interventions requiring particular capabilities.

One obvious problem is the failure of physical security. Security underwrites the predictability that makes an investment possible, and also the psychological assurance that one will be around to enjoy its fruits. Conflict has been a major brake on economic activity, especially in Africa. Where resources are involved, as in Angola or Nigeria, benefits are almost invariably captured by a small, self-interested elite.

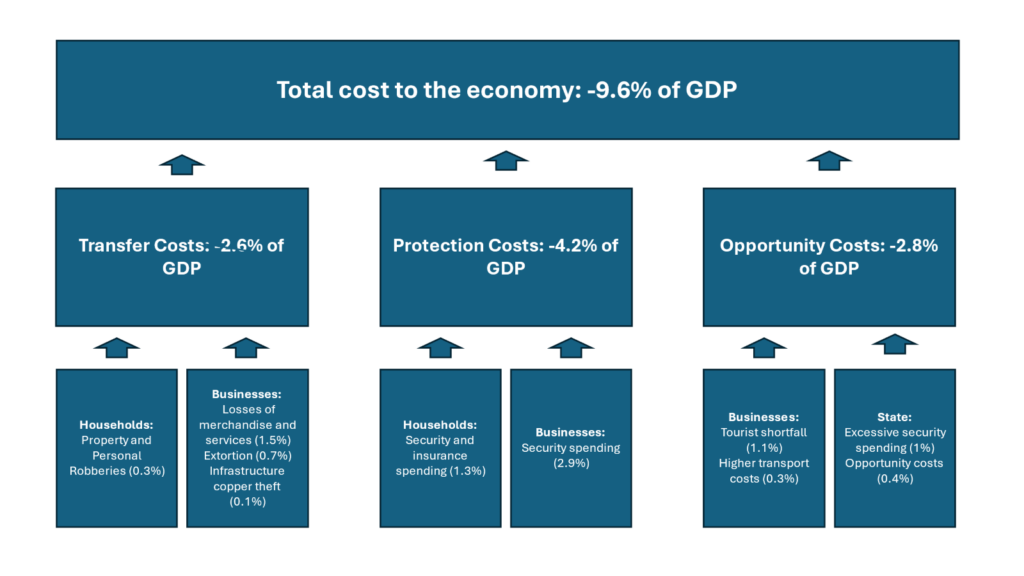

For South Africa, crime and violence – both against persons and property – has been a major drag on growth, and a major disincentive to investment. In terms of raw costs, a 2023 World Bank report put the costs of crime in South Africa at the equivalent of around 9.6% of the country’s GDP. Direct losses come in at 2.6% of GDP, expenditures such as security and insurance at 4.2%, and opportunity costs at 2.8%. This is distributed thus.

Criminality

The Global Organised Crime Index — which measures and ranks the state of organised crime across countries — gives South Africa an overall “Criminality” score of 7.18 out of 10 (higher scores reflect greater criminality) in 2023. This places South Africa at the seventh position globally, third among African countries, and first in Southern Africa. Its “Resilience” score — reflecting its institutions, calibre of leadership and similar — stood at 5.63 (higher scores denote better resilience).

This places it at position 50 globally, fourth among African countries, and first in Southern Africa. South Africa is, in other words, highly vulnerable by international standards to organised crime, but indifferently able to respond to it. Its favourable regional rankings should not be overstated, since South Africa has a highly sophisticated economy, with the need for resilience being consonantly greater than its peers.

This is aside from a high level of inter-personal and opportunistic crime, often marked by violence. Much of this is difficult to quantify, but if the numbers shown above are an indication (and they are bolstered by a number of other studies), the impact is likely to be stark and severe. It included businesspeople who are reluctant to consider ventures in South Africa because of concerns for their personal safety.

I recently spoke to a businessman about this: his (South African) firm pitched to a substantial contract to supply industrial equipment to an American counterpart, but the latter ultimately baulked at coming to inspect the plant as part of his firm’s due diligence.

Infrastructure

On infrastructure, the problems are well known. A reliable supply of power is foundational to a modern economy, and South Africa entered the democratic era with some of the world’s cheapest electricity, and a surplus to boot. The latter was rapidly consumed as electricity provision was expanded, but without a concommitant increase in generation.

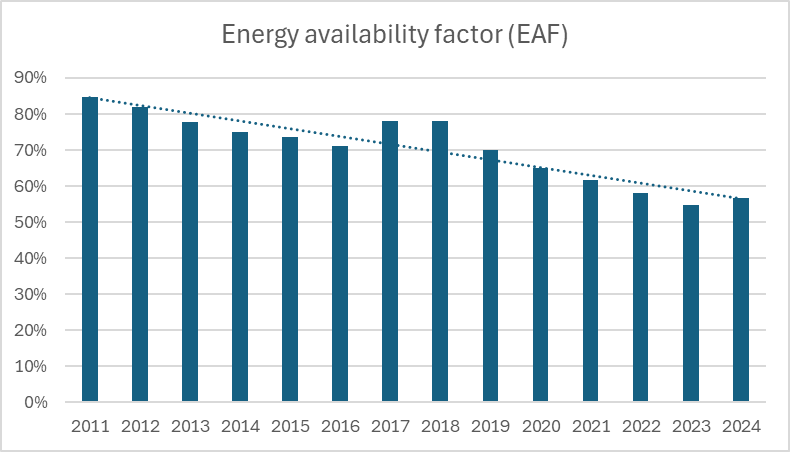

The upshot is that South Africa endured close to two decades of “load shedding” – while 2024 has seen a reprieve, it is unclear whether the crisis is over, still less whether the capacity exists to underwrite significant growth.

The Energy Availability Factor is a measure of power station availability that takes account of energy losses that are not under the control of plant management and internal non-engineering constraints. Its decline is apparent from this graph. In 1999, the EAF stood at 91%. When the first rounds of the power crisis hit, in 2007/08, the EAF was at 85%. In 2013, it dipped below 80%, and in 2020, below 70%. In 2024, it sat at a dismal 57%. In other words, over that period, South Africa’s EAF has fallen by a staggering 34 percentage points.

Rail transport is an essential hard sinew of transport, but the state of South Africa’s rail network has long been of concern. To illustrate this, in 2017, Transnet recorded shipments of 226 million tonnes; in 2022, this had fallen by over 30% to 154 million tonnes. In the latter year, the Minerals Council South Africa estimated that R50 billion in potential revenue through ore exports was lost as a result of Transnet’s failings.

The decline of the rail system has pushed ever more cargo onto an overused and undermaintained road network, with the associated costs, as well as safety concerns (drivers and their cargos being a target of criminal groups), as well as considerations relating to carbon emissions, a matter of not inconsiderable importance when goods are sold in environmentally conscious markets.

Costs and difficulties

Ports, meanwhile, connect a country with the world, making global trade possible. But research by the World Bank and S&P Global Market Intelligence, the 2022 Container Port Performance Index (CPPI), put the Port of Gqeberha (Port Elizabeth) at 291 of the 348 surveyed, Durban at 341, and Cape Town at 344. South Africa’s neighbours performed better, with Mozambique’s Beira at 223, Maputo at 248 and Namibia’s Walvis Bay at 293.

All of these push up the costs and difficulties of doing business, and hence also of investment. This is the case even – perhaps especially – for mining, the country’s foundational industry and an outsized contributor to its exports. Indeed, the inability to maintain these facets of the economic environment speak to an effective “demodernisation” of the economy, the wearing away of its foundations and the circumscription of its prospects in higher value-adding activities.

Human capital is the basis on which economic sophistication rests. Brain power is a more effective value multiplier than muscle power. The inadequate education received by too many of South Africa’s young people had been recognised since long before the transition, and has been a nominal priority for the government since.

Yet the state of education and skills development bespeaks nothing short of a profound crisis. Two respected international benchmarking exercises, the Progress on International Reading Literacy Study and the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study, illustrate the magnitude of the problem: 81% of Grade 4 pupils in South Africa cannot read for meaning, while just 41% of mathematics pupils and 36% of science pupils were proficient in basic skills and content.

In South Africa’s workforce, a 2022 study by the Labour Market Intelligence Partnership (LMIP) looked at occupational shortages. It used the Occupational Shortage Index – a composite measure of wage pressure, employment pressure, and talent pressure – to estimate skills shortages in South Africa.

The Index is expressed in scores over a range of -100 (indicating a surplus) to +100 (indicating a shortage); 0 represents equilibrium for a given occupation. The findings revealed significant shortages in managerial and professional occupations, with rates of 94.2 and 78.2 respectively. This points to the considerable dearth in higher-end talent. But even in the capacity for mid-level tasks, extensive shortages existed. The score for clerical support workers was 74.1, for plant and machine operators was 69.8, and service and sales workers was 60.4.

Filling skilled positions now is tough. There is little confidence that this will improve in future.

Public wellbeing

A regulatory environment is intended to safeguard public wellbeing. For many of us, the stock reaction is to decry “bureaucracy”; however, it is less the quantum of regulations that matters than it is their rational connection to outcomes, and the efficiency with which they can be implemented.

South Africa moves on a regulation-heavy path, and also one in which the benefits are doubtful and the capacity of the official systems to implement them is questionable to say the least. This is illustrated by inefficiencies in departments such as Home Affairs (regarding work visas) and the Department of Mineral Resources and Energy (in issuing mining licences), as well as instances of blatant incompetence and system breakdown (as in numerous municipalities, with matters ranging from the provision of water through to issuing accurate bills).

More than this, government policy has since the 1990s paired economic policy with political imperatives, aimed at advancing its “transformation” agenda. This has taken the form of affirmative action requirements, for “empowerment” deals and so on. All of this adds costs to doing business, and disincentives to investment.

Some years ago, both the American Chamber of Commerce and a survey of firms based in the European Union raised concerns about the costs and consequences of “empowerment” legislation. Then Minister of Trade and Industry, Rob Davies, commented that while the government would look at these concerns, no changes would be in the offing: “Localisation is not something we will be able to renounce. Nor are we going to be able to renounce BEE.” Note, though, that it is not that the government is “not able” to step away from these policies, but that it has chosen not to.

As my colleague Gabriel Crouse explained in his study of South Africa’s tax regime, the country has seen a rising quantity of government, but a declining quality. Indeed, Ricardo Hausmann’s Harvard Growth Laboratory identified the deficient quality of government as central to the country’s failings.

Willingness

This raises the question of knowledge – how government and other actors understand realities and bring their insights to bear in effective policy. As noted earlier, it was a willingness to take experience and evidence and to change course accordingly that made economic progress possible in a number of peer countries.

South Africa has been resistant to doing this. A deeply ideological view of the world, and the imperatives of mollifying particular interests, has meant a dogged refusal to act on experience, even where it has been negative. Its stance on labour legislation, racial empowerment and mining policy are testimony to this.

The late Lawrence Schlemmer once said that South Africa’s government excelled in one thing: issuing papers and plans that would never be implemented. It’s accurate to say that it’s unlikely that a state as disabled as South Africa’s – certainly for its level of development – would be able to exercise the sort of guiding influence that the government has aspired to (this in itself draws on the experience of some its peers, where industrial policy has played a role in their success).

Key to the deployment of knowledge in an economic setting is understanding the difference between what is desirable and what is feasible. This is often lost in South Africa, and its consequences are felt in each of the foundational factors underwriting economic success.

Heartbreak Hotel

These five factors need to be in place for a successful economy. The two surmounting them are described as “Heartbreak Hotel”. These are prioritising sectors and picking champions. Ironically, it’s at this level that a great deal of public attention to economic policy takes place.

This is the arena of Industrial Policy Action Plans, investment conferences and social pacting. In essence, the government has attempted to import political solutions (with which it is very comfortable) into the economic sphere (which it struggles to comprehend).

The basic premise has always been that the application of government power and resources could be a significant accelerator for the economy as well as an important mediator of the distribution of benefits. It would, in other words, help to drive growth while ensuring development, in the sense of economic resilience and rising living standards. This has taken the moniker of the “developmental state” and latterly the “capable state”.

This background is essential to understanding the course that the business environment has taken. As Dr Neva Makgetla put it: “Industrial policy presumes a mixed economy, where government has to manage private actors to achieve socially desirable aims, not simply seek to replace them with government agencies. An effective industrial policy thus requires a functional paradigm for dealing with business, as well as capacity to understand and respond to domestic and global economic developments that lie outside government control.”

Policy capture

Attempts at state promotion have often descended into effective policy capture, whether by labour, by entrenched business interests or by politically connected interests. XA Advisory’s Donald MacKay argues that in attempting to push agendas in trade and business promotion, South African industrial policy has undermined the entire basis of efficient market operations. It is no longer merely a case that certain firms or sectors are preferenced, but that the incentives have been skewed, so that a focus on competitiveness is giving way to one of rent seeking. It is increasingly difficult in some areas to determine what an accurate price should be. South Africa, he says, is becoming a “subsidy economy”.

Peter Attard Montalto, long-time market analyst, has observed a something similar, a belief that by persuasion and cajoling and by “counting” projects, investment and growth can be willed into being: “There [is] a strange belief evident in the countability of individual investments: if you just have more individual commitments from individual companies with rand amounts attached, and more hands on which to count them, you will be fine. In this conception, because a certain company is investing in this industry and another in another industry it’s a sign of life in each industry. Never mind if a handful of other investors have turned down opportunities or become frustrated and put plans on ice.”

Add to this such initiatives as Expropriation without Compensation, prescribed assets, the National Health Insurance, policy posturing that signals a reckless disregard for economic imperatives in service of ideology.

The reality is that the government simply lacks this expertise, and confronts a complex system with deep structural problems. Hence the terms “Heartbreak Hotel”. Lofty aspirations are crippled by the implausibility of the conditions in which they are being implemented and by the conflicting objectives and inabilities of those who hold them.

A devastating verdict on this was delivered in last year’s report on South Africa’s growth quandary by Ricardo Hausmann’s Harvard Growth Lab. It ascribed the predicament to two key factors – the effects of special exclusion, and the quality of governance. It might be added that to correct the former would require significant improvement in the latter.

So, what then is to be done? In the next and final part of this series, I’ll be exploring a set of policy proposals and how these will hang together. How, in other words, it can join the “best of the rest”.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend