Despite what you may read, or may believe, materially, life in 2024 for the majority of human beings is close to or is the best it’s ever been.

Life expectancies are at or close to the highest they’ve ever been across the world; deaths from war are, despite the recent uptick in global instability, still much lower than they have been for much of human history; poverty is diminishing in much of the world (South Africa is an unfortunate exception) by almost any metric you can measure; life in 2024 is better than at almost any other time except maybe 2019. (This is well documented on https://humanprogress.org/)

This is particularly true if you are secure in the middle class, regardless of which country you live in. Indeed, people in the globalized middle class are increasingly alike, no matter where they live.

An English-speaking middle-class kid growing up in India and going to a good school is likely to have a huge number of shared cultural overlap with a middle-class kid in England, America, South Africa, Poland or really any country that doesn’t live under a totalitarian government. The internet has created a global culture where people across the world can bond over shared experiences, and friendships can be built across the world. (Having grown up online, I am one of these people, having friends in Israel, the UK, America and Ukraine.)

And yet.

Mental health crisis

We often read about a global mental health crisis. Rates of suicidal thoughts, suicide and depression, particularly amongst teens, seem to be on the up in countries all over the world, but particularly the developed world. According to the Lancet Psychiatry Commission on youth mental health, “in many countries, the mental health of young people has been declining over the past two decades.” Whilst the global average for depression in young people is 15%, in the U.S. it is 40%. Some studies suggest that the decade between 2010 and 2020 has seen a 40% rise in depression and suicidal thoughts among young people.

Both boys and girls are affected, with teenage girls seeming to be worst off. However, girls and boys are responding differently. Girls seem to have higher rates of depression and suicidal thoughts, with 53% expressing “Persistent Feelings of Sadness or Hopelessness” in the American Youth Risk Behaviour Survey. The equivalent number for boys is only 28%. However this may be partly due to the tendency of boys to be less willing to seek help or admit to mental health problems.

Girls in developed countries tend to react to this crisis in a more public way, in an often-toxic relationship with social media. Mainstream culture, particularly youth culture, is filled with affirming messages about the strength and importance of women. By contrast, men live in a mainstream culture more hostile to masculinity, facing attacks from views of the world which cast men as privileged villains.

Ever greater loneliness

Many young men suffering from depression and alienation retreat into communities hidden from public view in anonymous environments like the image board 4chan, or online gaming community chat servers usually hosted on the Discord platform. Whilst for some, these platforms become lifelines, for others they are paths to ever greater loneliness and in some cases make young men vulnerable to radicalization into any and all extreme political ideologies. Many modern young men seem to be checking out of society altogether, and struggle to find a career, a relationship or even to join communities. Think of the modern attraction to extremist right and left movements among young men, and the popularity of people like Andrew Tate.

Indeed, while the mental health crisis may be worse for girls, mentally unhealthy boys will make up the next generation of criminals, terrorists and anti-social problem-makers in a way in which girls are less likely to do.

The mascot for these modern boys and young men has strangely enough become the actor Ryan Gosling of “The notebook” fame. In a number of films, Gosling has played a loner: handsome and in some ways mysterious, but also deeply isolated and unrecognized by society. He has played characters as diverse as “The Driver” in the movie Drive, to “Ken” from the Barbie movie, who share these traits.

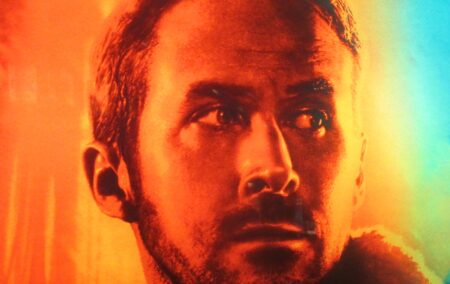

However, none of these Gosling characters captures the self-image of the depressed modern young male better than “Officer K” from the masterful film, Blade Runner 2049.

“Officer K” is a synthetic human, who works as a detective in the deeply dystopian future of the Blade Runner universe. He is handsome, has suppressed emotions (on account of being effectively a robot), competent at his work, but crippled by extreme loneliness. K has a girlfriend (played by Ana de Armas) who is quite literally a hologram, unable to be touched, and programmed to say whatever he wants to hear, depriving him of a real connection. (In a world filled with ever greater varieties of pornography and prostitution, and with declining rates of relationship and marriage, this point resonates strongly with many young men).

Broken and battered

K is also hated and discriminated against by society on account of his unnatural origin. The beginning of the climax of the film has a striking scene, with a broken and battered Officer K illuminated by the purple light of an advert for his holographic girlfriend. This iconic image has become the mascot for this type of young man.

Ultimately, in the film K discovers that despite his initial impressions he is not the “chosen one” and gives his life to protect others, dying largely unrecognized and alone.

So powerfully did this character capture a particular self-image, that it became commonplace in these male-dominated online forums to see people posting pictures of Officer K or similar characters, with the claim that this was “literally me”. In response, people made fun of such comments making the phrase “literally me” a meme in itself mocking self-important teen angst. (https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/literally-me-syndrome-wow-this-is-literally-me)

Whilst some of the attraction to the officer K character can no doubt be put down to the usual teen and young male angst (no one understands me!) it also captures something real in the experience of young males.

Rather than fantasising about being scrappy underdog heroes who get the girl in the end, or badass warriors who overcome any challenge, many young men seem to think that a lonely death is more likely to be their fate.

If we want a healthy and functioning society, where men play their roles and become good fathers, honest workers, and positive role models, we need to change our culture and lead people away from this nihilistic despair. I don’t, nor does anyone else have the answers at this stage, but it’s a problem that deserves more thought and attention. If responsible people don’t fill this space, predatory characters who prey on despair (like the aforementioned Tate) will continue to dominate the future of young men.

[Image: https://www.flickr.com/photos/93779577@N00/36845000154]

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend