If economic growth is what we want, we need policies that permit wealth creation. Redistribution destroys wealth.

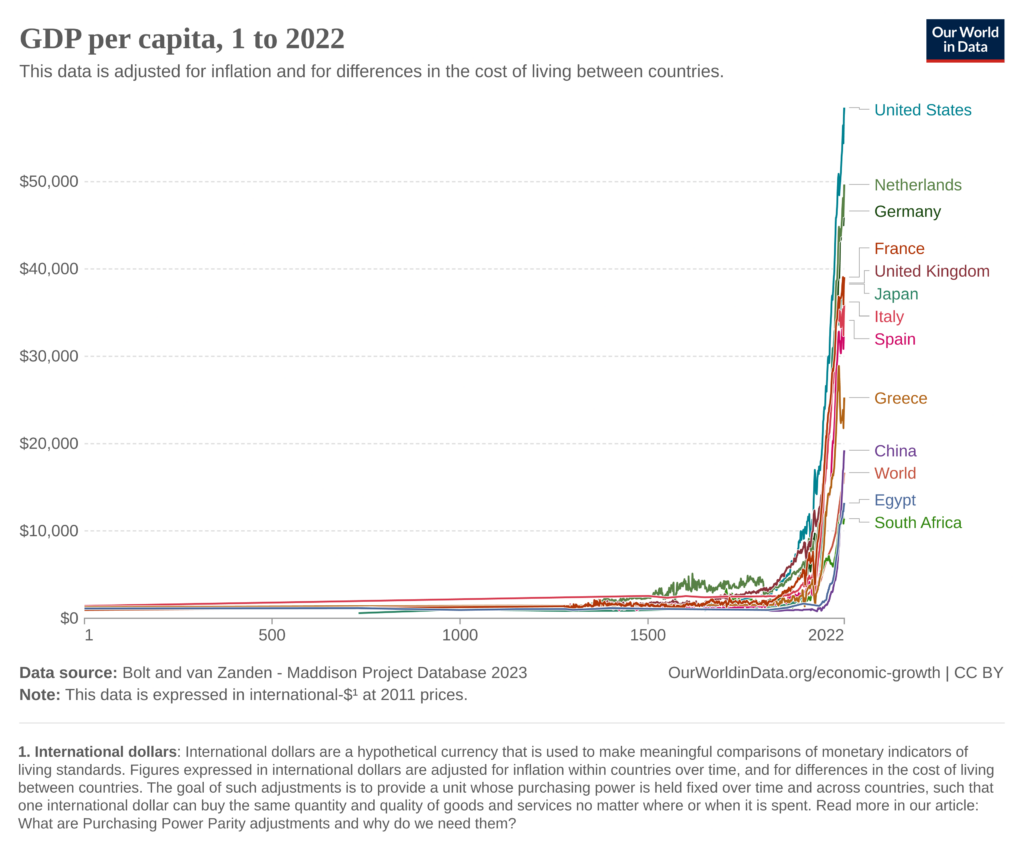

Wealth creation is a recent – and fragile – invention. Until about two centuries ago, almost everyone was poor, and nobody had figured out how to create economic growth.

The victors write history, and the poor were illiterate, which is why we read about the great wealth of the medieval nobility and the church, but they were a tiny minority. Everyone else was born poor, and could reasonably expect to die poor.

Part of the story is about technology, starting with the invention of the steam engine in the 18th century.

Another part of the story is about trade. If you look at the chart above, you’ll notice the extraordinary – for its time – wealth of the Netherlands starting in the 16th century, well before everyone else began to get richer. This was almost entirely based upon international trade.

Political economy

The most important part of the story, however, is about the political economy of the countries that learnt how to turn work into substantial wealth that could raise the living standards of a significant part of the population, even if they were not born into the nobility.

For the first time, people who worked to produce goods or services could not only expect to create more than they needed to satisfy their immediate needs, but expect to keep it.

This allowed them to accumulate capital. Those who were most successful at producing the things society needed became the owners of the most capital, which they were free to dispose of or squander as they wished, but which enough producers chose to use to buy more and better machinery, employ more people, or invest in other businesses.

They learnt to specialise. Division of labour, organised under private companies and supply chains, maximised the economic value that could be created.

They learnt to economise. They had a financial incentive to find smarter ways to use materials, to minimise their use of resources, and therefore reduce their costs.

They learnt to improve productivity by training and educating themselves and the people who worked for them.

Wealth earned

It is critical to acknowledge that the people who became richer in this fashion earned that wealth, by creating goods or services that other people valued highly.

Failing to serve the needs and wants of society meant failing to make a profit. Profit, therefore, signifies the value that someone creates, not for themselves, but for other people.

This process of creating wealth and investing it started a virtuous cycle. People who were good at improving the living standards of others – people we would call innovators or entrepreneurs today – would be rewarded by getting richer. This allowed them to employ more people and machines to produce more, and to invest in other people who were also good at serving people’s needs, which created more wealth, and so on.

Eventually, the wealth created in this fashion would grow so great, and spread so far, that most of the population was lifted out of the grinding poverty that had been the status quo in all societies for thousands of years.

Free market institutions

The critical institutions that facilitated this process were the right to own private property (that is, the right to keep what was earned and employ one’s own capital as one wished), and the ability to enforce contracts. In the most successful countries, these rights were assiduously protected by the state, which held the monopoly on force.

These are the institutions that free markets needed to function, and free markets are what generates prosperity and rising living standards by creating wealth.

Although serving the wants and needs of society is what gave production its social value, the motivation for people to produce more and better goods and services was not necessarily about serving society. It could be, but it didn’t have to be.

As Adam Smith wrote: “It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own self-interest. We address ourselves not to their humanity but to their self-love, and never talk to them of our own necessities, but of their advantages.”

Profit, therefore, was not only the measure of how well someone served the wants and needs of society, but it was also the incentive for doing so.

Fallacy of redistribution

All this, by way of background to the real point of this article: the terrible fallacy of redistribution.

Ever since the advent of market economies in the 18th century, what Karl Marx called capitalism also attracted its critics. It was unfair, they said, that in a market economy, some people became rich and accumulated capital, while others remained poor and had only their labour to sell.

Even if everyone became richer, they said, the unequal distribution of wealth was a problem. Society would be more just if only wealth were more equally distributed.

This was always a rather perverse argument. The process of creating wealth described above says nothing about its distribution, other than that those who create the wealth are entitled to dispose of it as they see fit. And on what grounds wouldn’t they have this right?

Whether they spend it on charity, or saving, or investment, or fripperies is not a choice anyone else has the moral right to make on their behalf. And dispossessing someone of the wealth they legitimately earned through voluntary transactions and voluntary contracts is a gross violation of their individual right to do with their own person and property as they wish. Where is the justice in that?

Marx himself recoiled from the idea that wealth ought to be redistributed. He described “fair distribution”, “even to those who do not work”, as “vulgar socialism” and “obsolete verbal rubbish”.

He believed not in a right to material equality, but in what he called a “right to inequality” grounded in the fact that people are unequally endowed with productive abilities.

Even Jesus taught that being unproductive entitles one to nothing: “For whoever has will be given more, and they will have an abundance. Whoever does not have, even what they have will be taken from them.” (Matthew 24:29.)

Incentives

While the intentions of those who believe in redistribution (like these left-wing economists who seek a wealth tax in South Africa) may be noble, the consequences of their ideas are highly destructive.

Redistribution doesn’t really redistribute wealth at all. It destroys wealth.

The reason for this is simple. Very few otherwise unproductive people who receive redistributed wealth are in a position to use that wealth to create more wealth. They typically either spend it on immediate short-term needs, after which the wealth is gone, or they neglect it, if the wealth comes in a form that isn’t easily spent.

We’ve established that creating wealth is both the consequence and the cause of improving the general living standards of, and reducing poverty in, society. Wealth filters through society by means of trade with other producers, as well as by employment (that is, the trade of labour).

Wealth redistribution distorts the incentive to create more wealth. It reduces the rewards for productivity, innovation and entrepreneurship. And because it reduces the reward, it also reduces the amount of risk that the owners of wealth are willing to take.

Just like with alcohol and tobacco, if you tax something, you get less of it. If you tax productive activity and wealth creation, you’ll get less productive activity and less wealth creation.

Redistribution also reduces the amount of capital available for investment. The recipients of redistribution have immediate wants and needs that must be fulfilled, so they are less likely to invest capital than the previous owners of that capital. They are also less likely to have the nous required to invest in successful, productive activity, nous which the previous owners demonstrated by accumulating the wealth in the first place.

Unintended consequences

Another unintended consequence of redistributive policies is capital flight, which further reduces the amount of capital available for investment and job creation. If redistributive taxes or other obligations (like black economic empowerment) are too onerous, wealthy individuals and companies will seek out other countries, where the rewards for risking investment are better.

Government intervention in the market to redistribute capital also distorts market signals, and in doing so, disrupts the natural allocation of resources.

In South Africa’s land restitution and redistribution programme, for example, nine out of ten projects fell into disrepair and disuse, because the recipients did not have the ability and resources to maintain the land in a productive condition. This is a dead loss to the economy of at least 90% of the value of the redistributed wealth.

The long-term consequences of reduced capital availability and reduced incentives to take risks, innovate and be productive are a stagnating economy. The loss of capital leads to fewer jobs, less innovation, and a general decline in the wealth-creating capacity of the economy.

In South Africa, which for three decades has implemented various redistributionist policies, the consequences are plain to see: GDP per capita has gone down, instead of up, and unemployment has gone up, instead of down. As I wrote earlier in the week, South Africa is not a developing economy, but an under-developed economy, by choice.

Politics

While wealth redistribution may be well intended, aiming to alleviate poverty and reduce inequality, its long-term economic consequence is wealth destruction.

It distorts incentives, reduces capital accumulation, disrupts market forces, fosters dependency, and encourages capital flight. Redistribution policies stifle the very factors that drive wealth creation.

Now it is true that there may be political reasons for some redistributive policies. It is proper to restitute assets that were expropriated from people under unjust circumstances in the past. It may also be reasonable to establish a minimal social safety net, especially in a country that suffers from structural inequality, as South Africa does.

However, policy makers should be mindful that redistribution is not free. It always destroys wealth.

Wealth creation is essential to sustain economic growth and improved living standards for all of society, including the poor. And these benefits are fragile. Redistribute too much of it, and growth vanishes, with dire consequences for everyone, especially the poor.

The primary focus of government ought to be to establish free-market policies that are proven to encourage productivity, innovation, and investment, instead of undermining them with excessive taxation and redistribution.

Leave those who have demonstrated the ability to create value, and create wealth, free to do so.

Wealth is created when individuals have a maximal incentive to work, to save, to invest, to take risks, to invent, and to trade. This virtuous cycle of wealth creation leads to a thriving economy that benefits everyone. Government intervention to redistribute wealth can only ever destroy wealth, on balance.

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend

Imahe: Even Karl Marx believed in a “right to inequality”. Shoe shiners working at Cape Town International Airport, ca. 2012. Photo: flowcomm on Flickr.