South Africa seems to be following the familiar downward spiral common to so many African countries. As IRR chief executive Dr Frans Cronje argues, the only thing that can possibly stop this is injecting the right ideas into the public sphere. Even then, however, those ideas must still be accepted by the rest of society.

The only chance we have of saving this country in the long term lies in a massive injection of individualist ideas. We must realise that we are operating in a society in which these ideas are both deeply embedded (as I believe they are in all societies, evident from the way human beings live), and foreign, in the sense that they are non-existent in public debate. Specifically, these ideas are new to many black people, at least those who had the sort of upbringing and education I had.

I grew up in a township, Madadeni to be exact. My experience of white people was largely limited to television and the few times I would go into town. Typically, the people from whom you learned about this other group of South Africans either told you that they were responsible for the obvious difference in wealth between the town and the township, or they told you that white people were superior and better at running things, inventing things, and so on.

The latter attitude is mostly shared by older people. Even as they hate the National Party, a lot of them seem to believe white people are superior. It is reinforced through many sayings, such as ‘uzenza umlungu’, meaning you are pretending to be a white person, usually if you display a preference for food other than what is available at home, or ‘izinto zabelungu’, meaning ‘those are white things’, when you ask about some scientific phenomenon or invention.

Radical leftist position

It is such a depressing position that it is no wonder most young people recoil from this looking down on oneself. The only widely-known alternative, however, is the radical leftist position.

The teaching of history in public schools reinforces the leftist narrative. The history I was taught tended to dismiss liberalism almost as if it were some fun but inconsequential pastime. The impression I got of the Soviet Union, for example, was that it would have been fine if only that nasty Stalin hadn’t killed Trotsky! Yet, in the same school, we were required to read Animal Farm, in which you encounter Snowball, who is more complex than the story we were told about Trotsky in history class.

Liberals simply did not exist in my intellectual world when I wrote a letter to Thabo Mbeki at the age of 12 or 13, demanding that South Africa implement communism and that we should intervene in the Chagos Island dispute, for some reason. I was a happy child, but I grew up to be an unhappy teenager because I truly believed that various forces were controlling my life.

I became aware of my inferiority complex when I went to UCT and spent significant periods of time around white people. I became hyper-defensive when it came to the African National Congress (ANC), because (I now realise) of the fear that was deep inside me, created by the attitude so many older black people hold that white people are in fact superior. I did not want to live in a world where I could never hope to be great. That may sound like a cliché, but it explains my feelings at the time.

At first I vehemently disagreed

The Damascus moment for me came around the time of the 2012 US Presidential campaign. I was still at UCT (at the beginning of 2011) and on my way to failing my second year undergraduate physics degree. I watched Ron Paul’s videos and at first I vehemently disagreed, but the more I watched and listened, the more he made sense. Why had no one bothered to teach me these things before?

At UCT, by the way, Gwen Ngwenya was the SRC president in my first year. On the only occasions I heard from her and other liberals on campus, the conversation was always about race and why racialism was wrong and impractical. Which is an important conversation to have, but I couldn’t help but contrast this with Ron Paul’s approach, where the most important thing was always the underlying principle and sticking to the principle in all cases.

There’s no denying that race is one of the major issues in South Africa, but the fact is if you’re poor and you want an employer, a business partner, or an investor, skin colour should be the last thing you worry about. In light of my experience, race is still the reason why so many people look down on themselves, but it is only a barrier to the extent that the individual believes the lie of racism, often spread by their own culture and society.

Individual is sovereign

Ron Paul began from the premise that the individual is sovereign, and, from there, showed why racism is wrong. Many other liberals understand the principle, but they often assume too much. In particular, the rush to a centrist solution before we have achieved a general societal acceptance of liberal principles is reckless.

We still have much work to do; compromise positions such as welfare, and tolerance for some regulation (generally all the positions to which liberals attach the prefix ‘social’, and everything other than justice, that is called ‘justice’) tend to confuse people who were in the position I was in. Do you believe redistribution is unjust, or not? If you do, say so.

We must continue putting our ideas out there to give those young people in townships a third option – should they ever be in a position to look for one. We cannot guarantee success, but we can guarantee failure if we do nothing, as in Zimbabwe, where it is still so hard to find a liberal (I would like to acknowledge my friend Rejoice Ngwenya for fighting the good fight in Zimbabwe under difficult circumstances) even after the devastation wrought by socialism in that country.

While we may debate the effects of social media and the web more generally, one thing it has done is make it possible to hear about ideas that are not approved by an editor or a government. If we are right that our ideas represent a fundamental truth about humanity, those ideas will win out in the end. But only if liberals are willing to talk about their ideas, talk about them until other liberals are sick of hearing them, and talk about them to the point where everyone in mainstream media, politics, and academia, has to acknowledge their existence even as they disparage or dismiss them.

Clear alternative

We do not need to promote redistributionist ideas; the ANC and EFF have that covered. Liberals must provide the clear alternative, not just in efficient governance, but in philosophy. Young people may be hungry, and therefore Malema is using their idealism to accumulate power for himself, but he is still appealing to a sense of justice. And if liberalism is about anything, it is about justice. We can win this fight if we try.

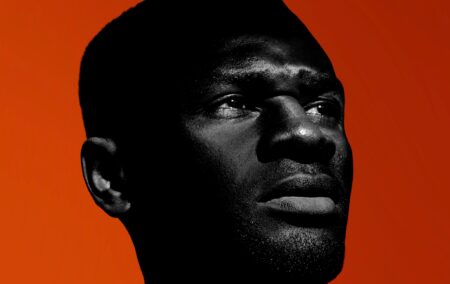

[Picture: Lucas Gouvêa on Unsplash]

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR

If you like what you have just read, subscribe to the Daily Friend