Ours is a story of tenacity – and one that matches continuing ideological stubbornness that needlessly impedes the nearly century-old liberal vision of a free, open and prospering society.

The battle of ideas that the Institute of Race Relations (IRR) is engaged in in 2019 began 90 years ago today.

It was a very different world – yet, though much has changed in the long interval since, the essentials are pressingly recognisable; we are still struggling nearly a century down the line to achieve the kind of society that acknowledges the indivisible interests of all South Africans, freed from the dead hand of statist interference and racial nationalist ideology.

By design, the IRR has not gone unnoticed for these 90 years, and has won acknowledgement on many occasions.

The most recent was none other than the ceremony last month at which President Cyril Ramaphosa bestowed national honours on the good and the great.

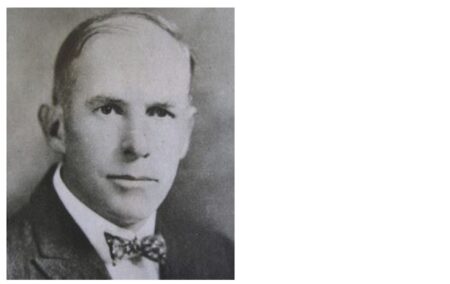

Two recipients – long dead – were posthumously honoured with the award of the Order of the Baobab (silver). This was a meaningful moment for the IRR and for Ray and Dora Phillips, immigrants from America, who were among our founders back in 1929.

If it’s likely very few South Africans had ever heard of them, we can claim the same is not true for the organisation they helped to establish.

In most news reports, just one line was devoted to them: ‘Ray and Dora Phillips, who were founders of the South African Institute of Race Relations, posthumously received a silver Baobab.’

One report acknowledged another element of the citation – their “excellent contribution to the creation of the first social work network designed to improve the terrible living conditions of the growing population of the oppressed that were being brought to the Rand to work in the mines in the early 20th century”.

Born in 1889, Ray Phillips’s fascinating life’s journey as a missionary and visionary of South African civic activism began with his ordination in late September 1917 in the newly built Pilgrim Church in Duluth on the Minnesota shore of Lake Superior. He and Dora came to South Africa a year later, and remained for the next 40 years.

In the larger chronicle of events since, the Phillipses’ contribution might seem little more than a marginal footnote, discountable, if not entirely forgettable.

But there are two reasons why ‘discountable’ would be a false calibration – both of their contribution and of the history South Africans have endured since the early 20th century. Both reflect the condition of a society still grappling with challenges that were as fundamental to its emerging modernity as they are to its future.

It was this that impelled the gathering at the Phillipses’ Johannesburg home on 9 May 1929, and the founding that day of the IRR.

Present on that occasion were Davidson Don Tengo Jabavu, one of the first professors at the University of Fort Hare; Johannes du Plessis, a missionary and theologian; Charles Templeman Loram, chief inspector of ‘Native education’ in Natal; scholar Edgar Brookes, (elected in 1937 to the Senate by black voters in Natal, and, later, elected chairman of the Liberal Party); J Howard Pim, the government official after whom the Soweto suburb of Pimville is named, Pim having dedicated much of his energy to black ‘upliftment’ in Johannesburg; Thomas W Mackenzie, editor of The Friend newspaper in Bloemfontein; and J H Nicholson, the mayor of Durban.

At a distance, the 1929 assembly of founders seems almost unlikely, and might at the time have seemed a conclave of unorthodoxy without a future.

Yet, as South Africa drifted steadily towards its most disastrous period – the inauguration of apartheid in May 1948 – the IRR became only more impelled to engage society, to monitor and analyse the national condition, to formulate arguments to resist the looming calamity, and to hold the spotlight on the prize of a free and open society.

We were unpopular, but dogged, certain of the persuasive impact of our data and the arguments we built on it.

In the years since, it is a measure of the endurance and the reach of the IRR that its research and analysis has appeared in media over the past month in places as diverse as London, Karachi, Lagos, Manila, Berlin, Caracas and Beijing.

For the most part, the arguments we advance today are little changed.

At a telling juncture in our national story, we encounter the IRR in one of the monumental documents of the apartheid period – Nelson Mandela’s final statement from the dock in the Rivonia Trial on April 20, 1964. The prisoner who would later become democratic South Africa’s first president told the court: “According to figures quoted by the South African Institute of Race Relations in its 1963 journal, approximately 40 per cent of African children in the age group between seven to fourteen do not attend school. For those who do attend school, the standards are vastly different from those afforded to white children.”

We might marvel, reading this, at how far we have come since those dark times. But it is sobering that, in 2018, IRR research on schooling showed among other things that just under half of children who enrol in grade one will make it to grade 12. Our economic data reveals a commensurate skills deficit in an unemployment rate for black people that is between 4 to 5 times higher than for white people.

The battle of ideas continues. In this, the IRR remains an unignorable participant in South Africa’s national conversation – for it focuses as it did all those years ago on the continuing struggle for modernity, freedom from poverty and the abuse of power, and the empowerment of individuals as the agents of a new society.

Ray Phillips foresaw it in two books in the 1930s, The Bantu Are Coming – the basis of his 1937 Yale University doctoral dissertation – and The Bantu in the City.

But for far too many South Africans today one would need only erase the word “oppressed” from that stirring phrase in the Phillipses’ Baobab citation – ‘the terrible living conditions of the growing population of the oppressed’ – to describe a mostly urban reality which existing and envisaged state policy exacerbates more than relieves.

Morris is head of media at the IRR. This article incorporates Morris’s Business Day column of 6 May.

If you like what you have just read, become a Friend of the IRR if you aren’t already one by SMSing your name to 32823 or clicking here. Each SMS costs R1.’ Terms & Conditions Apply