It’s hard to fault the rationale impelling South Africa’s continuing name-changing mania that a good society is one that expunges imagery that uncritically honours the dishonourable.

At first glance, it’s hard to fault the rationale impelling South Africa’s continuing name-changing mania that a good – or a better – society is one that expunges ‘names, symbols and imagery that uncritically honour those whom history has shown to be dishonourable’.

This, the reasoning goes, is a society that recommends itself on the grounds of being ‘more inclusive and reflective of diversity’.

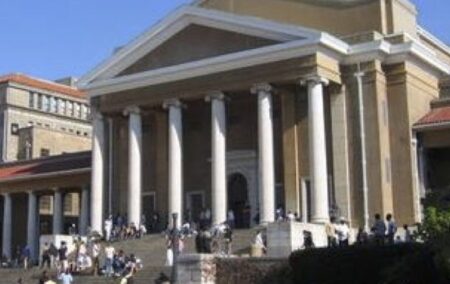

These quoted phrases come from documents on the latest round of name-change debate at the University of Cape Town, a perennially troubled institution now engaged in further disentangling itself from its own history by seeking replacements for ‘dishonourable’ associations.

The process has been going on for some time, the latest change having been the switch in December from Jameson Hall to Sarah Baartman Hall as a gesture, we are persuaded, of reasoned contempt for ‘the dishonourable history of Leander Starr Jameson’ [notorious co-conspirator in the Jameson Raid on the Transvaal in 1895], while ‘simultaneously (providing) an opportunity to recognise the multifaceted struggles and resilience of South African women’.

The latest object of shame is the M R Drennan Anatomy Museum, which UCT says ‘currently honours someone who was complicit in obtaining unethically procured human remains’.

And who could doubt how important it is to grapple with the lasting consequences of Britain’s imperial ambitions in Paul Kruger’s gold-rich republic at the turn of the 19th century, or the implications of the collision between science and moral sentiment?

No controversy there. But one does wonder whether the opportunity to make good on the flaw of ‘uncritically’ honouring anyone in the past is served by expunging them. If erasure is all it takes, there’s not much to be expected in the way of critical engagement.

In this light, erasure does seem an unimaginative and even quite petty gesture of triumphalism, one of whose by-products may be creeping intellectual atrophy, and another, public amnesia and the misplaced comfort that comes with imagining history as a cleaner, less contradictory episode than it actually ever is.

More than anything, them-and-us – or good-and-bad – thinking gets in the way of seeing this powerful truth about South Africa that, for all the divisive ideas that have shaped lives and behaviour, ours is a society whose communities have become steadily more, not less, embedded.

I wrote this week about how it often seems that South Africans ‘reach with easy familiarity for identities forged for them by historical figures they loathe, values they reject or forces they regard as spent’.

These are words I used a few years ago as a prelude to saying: ‘Asking South Africans to change their political allegiance is still often akin to asking them to deny who they are.’

Yet, this was ‘not universally true, or fixed, today, and it was not universally true of the past either’, I went on, citing as an arguably obscure example National Party MP Bruckner de Villiers ‘being carried shoulder high into parliament by coloured supporters who, in the 1929 election, had helped him secure the Stellenbosch seat’.

This minor historical vignette came to mind after reading two fellow Business Day columnists in recent times against the backdrop not only of the May election, but the greater battle of ideas – as we at the Institute of Race Relations call it – in favour of principles and policies capable of assuring South Africa’s potential as an open, free and prosperous society.

Last month, Steven Friedman alerted (middle class) readers to the risk of misjudging the mass of voters when he wrote: ‘They know the government is often corrupt or arrogant and don’t like this any more than middle-class voters (but) support the ANC as long as they do not believe the corruption has become so serious that it wipes out the benefits they receive.’ Like any political thinking, this was open to debate, but it wasn’t ‘irrational’.

Some weeks earlier, Jonny Steinberg tested the question ‘How much power does an SA president actually have?’ by turning it around to ask: ‘How governable is SA?’

‘The short answer,’ he decided,’ is: not very. A governable country is one in which levels of trust and common feeling run high. It is when people believe they are in the same boat, their destinies mutually entwined, that they make sacrifices for one another.’ In the absence of such common feeling, ‘to defer anything to the future is to put one’s fate in the hands of strangers’.

Both Friedman’s and Steinberg’s thinking reminded me of Bruckner de Villiers in 1929 – and after.

Midway through his term as Stellenbosch MP, De Villiers sided with D F Malan in rejecting the amalgamation that created the United Party, affirming instead the purified white nationalism which, a decade later, bore apartheid.

The first irony in De Villiers’s story is his defeat in April 1938 by the United Party’s Henry Fagan, who would chair the Fagan Commission of the mid-1940s which argued for race-law reform, especially relaxing influx control over black people in urban centres.

De Villiers’s party responded with the Sauer Commission, the progenitor of apartheid policy.

The second, almost poignant, irony – given the enthusiasm of those doubtless rational coloured supporters in 1929 – is that the MP is today memorialised in the Bruckner de Villiers Primary School in Stellenbosch’s Idas Valley, which, under the Group Areas Act of 1950, became a coloureds-only suburb.

It is not anymore, not by law, but, as elsewhere in South Africa, apartheid forged divided destinies, identities, and ways of thinking that continue to shape popular choices – as much as middle-class thinking.

The bridge that links the ‘strangers’ of Steinberg’s conception, and unifies the rationality addressed by Friedman, is the greater truth of South Africans, even if their personal histories obscure it. We are, as IRR polling repeatedly demonstrates, a country of more common than clashing interests. Affirming them, though, does mean defeating ideas, old and new, that were and are intended only to divide us.

And, dare one say, resisting the idea that merely changing the names of streets, towns or public buildings really is enough to deliver a society that is ‘inclusive and reflective of diversity’.

Nobody would lose any sleep if a modest no-fee public school in Stellenbosch’s Idas Valley were to ditch its name because of a morally irksome association. But it may be useful to remember that the association is not as neat as it might at first appear.

Morris is head of the media at the IRR. This article incorporates Morris’s Business Day column of 8 April.

If you like what you just read, listened to or watched, become a Friend of the IRR if you aren’t already one by SMSing your name to 32823 or clicking here. Each SMS costs R1.’ Terms & Conditions Apply.