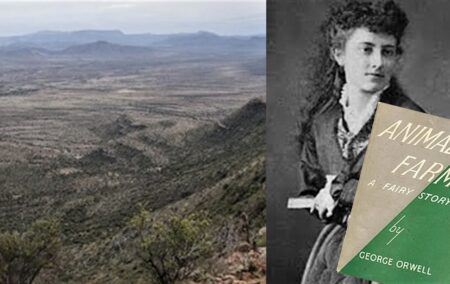

South African novelist Olive Schreiner’s century-old insight into the fundamental unity of South Africans’ interests continues to be fiercely resisted by adherents of the ideology laid bare by George Orwell.

The first edition of George Orwell’s chilling portrait of totalitarianism, Animal Farm, was published with the subtitle, ‘A fairy story’.

In the decades since, millions might well have wished the same was true of the reality Orwell’s satire portrayed.

In the novel, the hard-pressed animals perceive their redemption to lie in revolt against the uncaring farmer, who, once overthrown, is replaced by a new authority vested in seven commandments which seem to encapsulate a new fair future of egalitarian justice.

But, as time goes on, the original commandments – among them ‘Whatever goes upon two legs is an enemy’; ‘Whatever goes upon four legs, or has wings, is a friend’; ‘No animal shall kill any other animal’; and ‘All animals are equal’ – gives way to the unfussy authority of simpler maxims.

The first of these is, ‘All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others’, and the second – as the pigs on the farm become more human – ‘Four legs good, two legs better!’

This, the Wikipedia entry on the novel notes, ‘is an ironic twist to the original purpose of the Seven Commandments, which were supposed to keep order within Animal Farm by uniting the animals together against the humans and preventing animals from following the humans’ evil habits. Through the revision of the commandments, Orwell demonstrates how simply political dogma can be turned into malleable propaganda.’

This is all worlds away from South Africa in 2019. And yet, of course, it isn’t at all.

Every other day, efforts to deepen and expand liberty, to stimulate prosperity, to recognise citizens as members of an indivisible society are confronted with hostility from ideologues for whom the ideas that created the tyranny Orwell so deftly reconstituted in the farmyard setting of his novel remain paramount convictions.

In its most puerile but no less damaging form, none other than Nelson Mandela’s daughter, Zindzi, South Africa’s ambassador to Denmark (hard though that might be to credit), indulged in her own malleable propaganda recently by referring to ‘trembling white cowards’, ‘Thieving Rapist descendants of Van Riebeck’ (sic) and ‘shivering land thieves’.

Beyond being reckless and destructive, such comments are in any event very different from the hopes and thoughts of the bulk of South African society, as the IRR’s latest Hope report, Unite the Middle, makes clear.

That 88% of all respondents – and 86% of black respondents – agreed that we all ‘need each other for progress, and that there should be full opportunities for all’ is a clear indication of a common South African interest the Zindzi Mandelas of this world are content to overlook, and to undermine.

What is also evident from our polling, however, is that popular sentiment is prone to the constant harping on race, along with the failure of so much policy since 1994 to overcome inherited disadvantage. One of the effects is that most poor, unemployed and under-educated people today are black. As empowerment policy has failed in the main to reach the poorest, many may be tempted to see the association between continuing disadvantage and skin colour as a result of discrimination – an impression racial nationalist rhetoric seeks cynically to affirm. Thus, the IRR’s polling shows, the proportion of black people who think whites should take second place in South Africa has grown from 29% in 2015 to 62% last year.

Whatever the reasons for this change, manufactured division has long been South Africa’s biggest threat.

There is no link between Orwell’s vivid exposure of the brutishness he saw in communism and the novel that arguably assured Oliver Schreiner fame and attention, The Story of an African Farm – other than that the word ‘farm’ appears in both titles.

It is doubtless true that Schreiner’s world view, her humanist values and distrust of political radicalism, chime with Orwell’s.

But the counterpoint to the divisiveness that leading politicians are still so fond of is contained in a passage in Schreiner’s posthumously published Thoughts on South Africa (1923). Here, we encounter a notion that not only survived nearly half a century of apartheid, but remains vigorously and unignorably true of the country in 2019.

‘Wherever a Dutchman, an Englishman, a Jew and a native are superimposed,’ she wrote, ‘there is that common South African condition through which no dividing line can be drawn …. South African unity is not the dream of a visionary, it is not even the forecast of genius … [but] a condition the practical necessity for which is daily and hourly forced upon us by the common needs of life: it is the only path open to us… it is this unity which must precede the production of anything great and beautiful … by our people as a whole….’

To Schreiner’s question – ‘How from our political states and our discordant races, can a great, a healthy, a united, an organised nation be formed?’ – one could well offer as an answer the sentiments of most South Africans today.

In our survey, the pragmatic conception that better education and more jobs will in time ‘make the present inequality between the races steadily disappear’ was endorsed by a full 76% of all respondents, and 74% of blacks.

But it’s an open question whether South Africa’s political leaders want this to happen. They seem to set greater store by preserving rather than overcoming conditions that – despite a quarter century of supposedly non-racial policy meant to deliver better lives for all – continue to align so closely with race.

Morris is head of media at the Institute of Race Relations

If you like what you have just read, become a Friend of the IRR if you aren’t already one by SMSing your name to 32823 or clicking here. Each SMS costs R1. Terms & Conditions apply