Few things are more important right now than figuring out (using actual figures) whether lockdown works. As our lockdown strains the fabric of society and sends millions into deeper poverty, the question is: if not lockdown, then what? New evidence suggests an answer.

To understand whether the lockdown has worked thus far in South Africa, one has to throw one’s mind back to that now seemingly distant date of 15 March. It was a Sunday. President Ramaphosa was expected to address the nation at 5pm. The time was later pushed back to 6pm, but he eventually spoke just before 8pm. The suspense was gripping. Finally it came; Ramaphosa’s speech was worth the wait.

‘Never before in the history of our democracy has our country been confronted with such a severe situation,’ the President intoned with all the gravity he could muster.

Ramaphosa declared a National State of Disaster at Cabinet’s behest, the constitutional merits of which, and absence of parliamentary oversight, have subsequently been been challenged. But at the time, in the expectation of both rationality and oversight, the declaration seemed correct.

Ramaphosa also declared that a travel ban would be imposed on several countries on 18 March, that gatherings of more than 100 people were banned, and schools would be closed too. Shortly after his speech, the sale of alcohol after 6pm was prohibited.

These regulations were light, but the President noted that ‘this situation calls for an extraordinary response; there can be no half measures’.

As the regulations were so light, something else was clearly intended to do the ‘no half measures’ heavy lifting, and the key element in Ramaphosa’s sentence above was ‘calls for’.

‘We call on all business including mining, retail, banking, farming to ensure that they take all necessary measures to intensify hygiene control. We also call on the management of malls, entertainment centres and other places frequented by large numbers of people to bolster their hygiene control.’

The list of ‘calls’ went on, and the few hard regulations imposed were said to ‘encourage social distancing’ as backup to the ‘call’ for voluntary action.

‘In essence, we are calling for a change of behaviour amongst all South Africans,’ the president said, and this ‘call’ amounted to ‘the most definitive Thuma Mina [call on me] moment for our country.’

Ramaphosa was not alone. Every single parliamentary party leader joined his ‘call’ on private citizens to take extraordinary measures to socially distance.

‘We are led!’ was the answer to this call from millions of eagerly masked mouths. Everywhere I looked, South Africans were changing their behavior, elbow-greeting, scrubbing, self-isolating as far as possible, and gearing up to help the needy.

This then was the great Call Up to klap Covid, combining light regulations with heavy voluntarism –and you could see its effect from space.

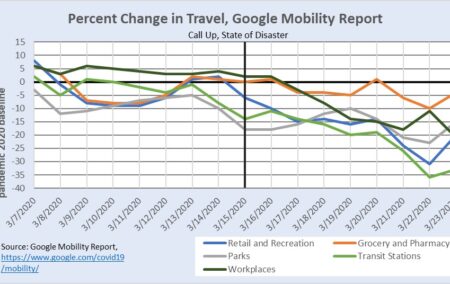

The source for these data is the Google Mobility Report, and there are limitations. Not every traveller has a smartphone, and not everyone who does have a smartphone has ‘locations’ permissions to Google. So, these data could either over- or under-estimate the real change in mobility.

Still, what the data do indicate is that there was more travel to workplaces than usual until Ramaphosa’s ‘call’. But after that, workplace visits dropped by 15%, and then by over 20% on the next Monday, 23 March. Travel through transit stations dropped even further – over 30% by the next Monday – while visits to shops and places of recreation and parks were significantly down too.

Because this data is incomplete, it is important to look for corroboration, or falsification, of the hypothesis that people changed their behaviour fundamentally before lockdowns elsewhere.

The data for the above graph is drawn from Citymapper, an app widely used to plan trips on public transport or on foot (not in cars). The relevant portion of Londoners dropped their travel rates by almost 80 basis points before their lockdown, after which there was a further dip (by another 10 basis points) that slowly increased again.

Berlin gives an even more stark case, with daily trips coming down by more than 80 basis points before lockdown and then an actual increase through April into May during heavy lockdown. And then, after the lockdown eased further, trips dropped once more.

Perhaps Citymapper data are anomalous, one might think, since they cover travellers who are not using cars. So we return to Google’s Mobility data at national level.

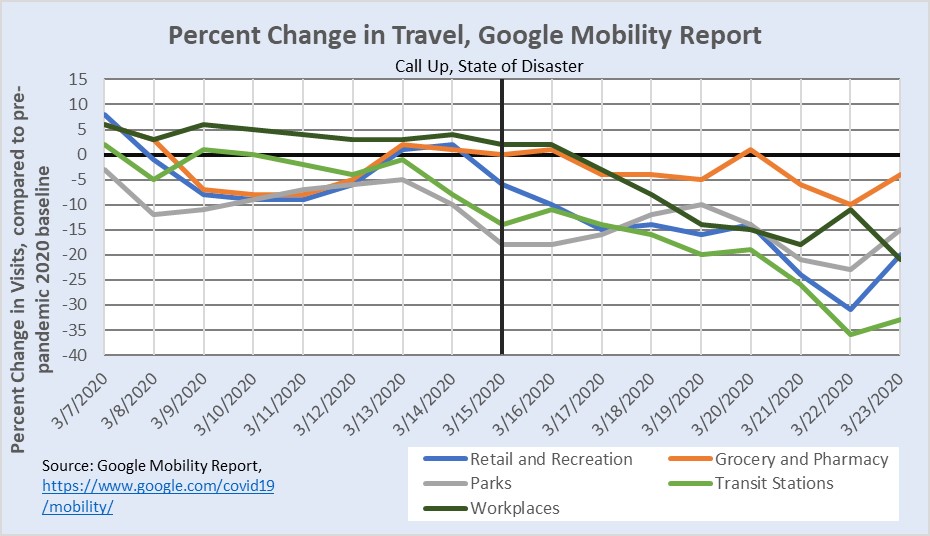

Before its national lockdown, German workplace visits were already down by nearly 40%, which is roughly where they stayed throughout lockdown. Transit, retail, and recreational visits were already down by about 60% before lockdown, from which point they increased slightly during lockdown. Parks and residences were visited more often before, after and during lockdown, which sounds very nice.

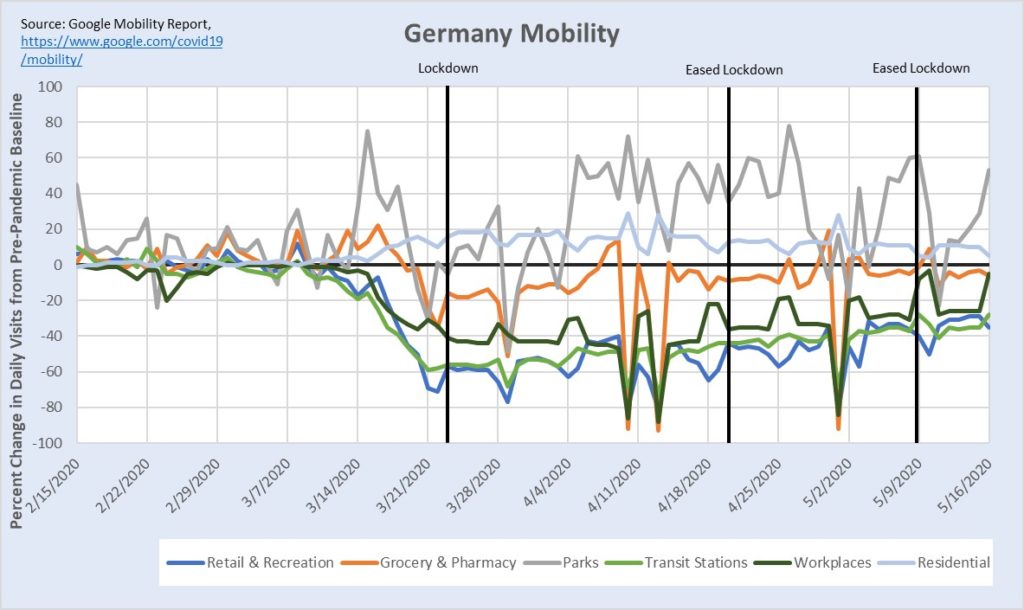

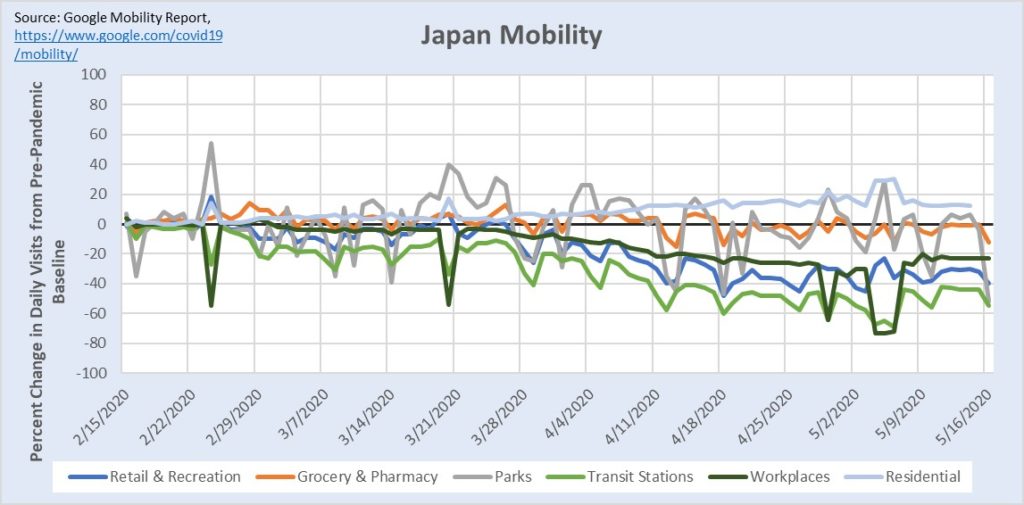

Japan had a Call Up like ours, but no lockdown. Still, you can see sustained shifts in travel behavior patterns from March through May.

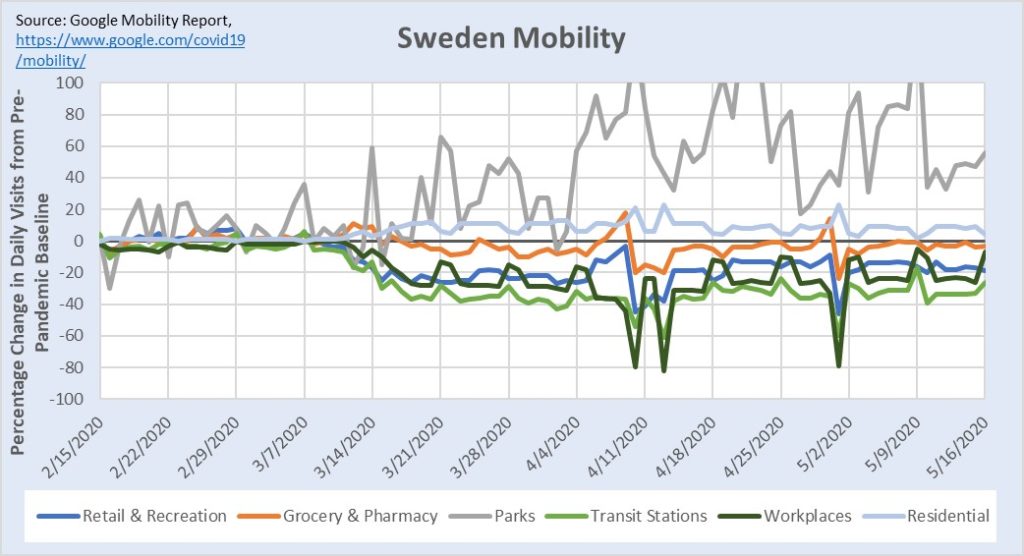

Swedes visited parks a lot more, but, again, the Call Up (without lockdown) had clear effects in massively reducing visits to retail, recreation, and workplaces, and less traffic through transit stations too.

Power of Call Up

From the above, one can infer three things: 1) People do change their behaviour en masse in the absence of brute force to coerce them; 2) such changes have coincided with the reduction of the reproduction rate of the novel coronavirus to below R = 1 (in Japan and Sweden); and 3) South Africa saw a marked change in nationwide mobility after the Call Up but before the lockdown. Together, this strongly suggests that South Africa’s Call Up was en route to significantly flattening the curve.

Here is the moment when you might ask yourself if a mere journalist has the authority to claim that Call Ups are genuine alternatives to lockdowns?

Consider this study from Johns Hopkins University in the United States. Like me, these scientists ‘use real-time mobility data derived from mobile phones’ to ‘demonstrate evidence that social distancing was already under way in many US counties before state or local-level policies were implemented. This study strongly supports social distancing as an effective way to mitigate Covid-19 transmission in the US’. I must emphasize that, in this study, the social distancing that is shown to be effective is voluntary social distancing, as distinct from that decreed by legal statute.

Next, consider this study, published by the Centre for Economic Policy Research, which begins: ‘(While) the Swedish authorities advised citizens to adjust their behaviour in the face of the pandemic, one may ask if the spread of the pandemic would have been more limited if the government had imposed a proper lockdown instead?’

The scientists compare actual Swedish data with a model of how Covid-19 would have spread if that government had also imposed a lockdown on top of the Call Up. The scientists find the two results are ‘not systematically different’ which ‘suggests that the infection dynamics in Sweden would not have been different in case it had imposed a lockdown’. In other words, the Call Up, and that a lockdown would have added practically nothing.

Then, for contrast, consider this study, which was used hastily by the NYTimes to claim that, had lockdowns in the US been imposed a week earlier, roughly half as many people would have died.

This study significantly focuses on New York City, the world’s biggest hotspot, but fails to even implicitly acknowledge the distinguishing factor of that great city, which is that its mayor, four days before lockdown on 11 March, encouraged people to act as ‘normal’ and telling people ‘not to avoid restaurants…If you’re not sick, you should be going about your daily life’, while criticising national travel bans.

This study outright ignores any difference this anti-Call Up might have had and effectively discounts all actual Call Up measures too. It uses historical data to ‘prescribe’ all mobility until 15 March, but, thereafter, finds census survey data no longer representative ‘due to changes of mobility behavior in response to control measures’. From a data point of view, voluntary social distancing is obviated tout court.

The upshot is that some scientists find it easy to conclude that lockdown works if they just ignore all Call Up effects. Meanwhile, other scientists who take the Call Up seriously find it to be far more potent than lockdown, even finding lockdown has no measurable effect at all.

Call Up advantages

Mere mobility figures do not tell the full Call Up story. After the Call Up, here and around the world, businesses responded in kind, masking their staff, and sanitising customers’ hands while requesting them to keep social distance. Yet more businesses sought ways to keep production going while keeping workers safe.

In addition, not all places are equally dangerous spread-points for the novel coronavirus. Wherever people shout, hug, dance, or smooch, the risk of viral spread is much greater. In South Africa, the most dangerous spread-points have often been funerals. It is exactly these high-risk spread-points that are most affected by Call Ups, here and elsewhere, as these are exactly the gatherings that are most shunned when the national message is to socially distance.

And if shunning is not enough, in a Call Up scenario the police are more capable of both enforcing bans on large gatherings, and supervising social distancing when long queues are unavoidable, because they have fewer other diktats to try to impose.

So, Call Ups should be significantly more powerful than the mere drop in mobility numbers suggest, depending both on the quality of social distancing they reinforce and the kinds of gatherings they inhibit. This must be a vital factor in explaining Covid-19 repression in Call Up-only countries like Sweden and Japan.

It is not all good news on the Call Up side of the equation, however. PANDA, an independent group of South African experts, estimated that the detrimental effects of the lockdown will cause 29x more lost life-years than Covid-19, but, on reflection, this is to be revised. The voluntary changes associated with Call Up and the lockdown were conflated in their analysis, though both had deleterious economic effects.

PANDA is aware of this and Nick Hudson, one of its leaders, assured listeners of the Daily Friend podcast that they were working on a delineation of lockdown and Call Up economic effects post haste. PANDA has shown real scientific grit, rather than blindly mining data to reinforce their initial position, in facing data frankly and adapting their position accordingly. The next PANDA report is therefore eagerly anticipated.

In the meantime, the assumption is strong that, for the same viral suppressive effect, Call Up damage to the economy is several factors less than economic damage due to lockdown. That is because the Call Up decentralises decision-making while allowing continued value-add in smart, particularised ways. The lockdowns, by contrast, crush business with an iron – and, in South Africa’s case, irrational – fist.

Call Up Vs Lockdown in SA

Clearly our lockdown had an extreme effect on repressing mobility. But I have already explained that this alone is not a great indicator of how well the virus is being repressed. South Africa will likely prove to be one of the world’s leading examples of this point in years to come, since we have had extraordinarily low mobility while the virus has continued to spread exponentially.

The president has repeatedly said that if people don’t move, the virus can’t spread, but we have proved more than anywhere else on record that people can move only a little while the virus spreads a lot. Why is that? I argue that it is precisely because our lockdown has twisted the nation out of all rational shape.

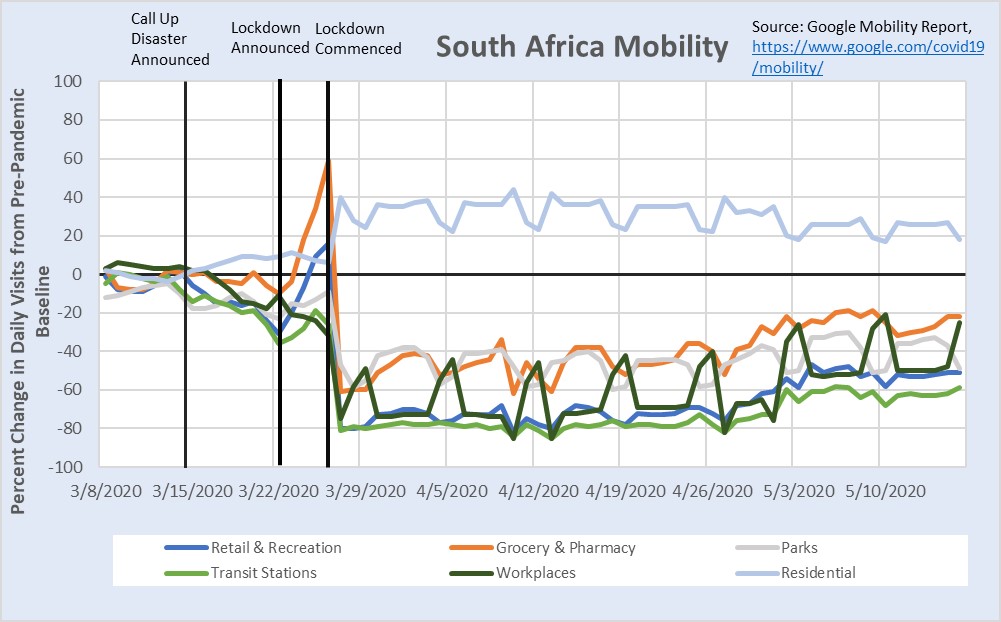

As you can also see from above, the national ‘Call Up’ was followed by a steep decline in mobility, but that was then inverted immediately after the lockdown was announced on 23 March, a Monday night, to be implemented at midnight on Thursday 26 March.

The intervening three days were chaos. In anticipation of the lockdown, grocery and pharmacy visits sky-rocketed to 60% more than the pre-pandemic norm and retail visits spiked, while transit stations were used more often too.

Think back to those long queues, the stifled aisles, the millions desperately trying to follow our sincere national Call Up to be careful and socially distance while also panicking about getting enough food to last in the throngs of the mob. Even before the lockdown was implemented it was perversely driving people closer, screwing the Call Up.

Since then, the catastrophic loss of more than a million jobs in this country – still mounting – has already driven many into hunger queues and starvation mobs where social distancing is often not observed. So, while the mobility during the lockdown has been extremely repressed on Google’s data, it likely misses out many of the most dangerous spread-points in the country, the mobs and hunger lines.

In addition, as the lockdown persists, people are not only get poorer, but also increasingly lose respect both for the experts insisting on the lockdown and the Rule of Law itself. That increases the chance that, when the lockdown is lifted, the Call Up to stay alert, be vigilant, and keep super careful while adding value to others through work will have reduced efficacy. The call is only answered by people who trust in leadership and one another.

Call Now

We in South Africa need to end the lockdown not because it worked, but precisely because it has been such a humanitarian disaster. That puts us in a different position to much of the developed world. We have to end lockdown and reduce viral spread at the same time.

The only way to begin to think about how to do this is to remember the Call Up. Remember the delight we took in taxis adhering to 50% capacity and high levels of sanitation while buses were sprayed clean; remember the alacrity with which businesses, both brick-and-mortar and e-commerce, reshuffled the decks for value-add in the time of voluntary social distancing; and remember the spirit of collaboration when it was us against the twin evils of the virus and impoverishment.

Now we have a third enemy, too; those who insist on lockdown without rhyme or reason. Do not be as deranged as they are. Remember when we were led, before we were misled. To get back to true leadership the iron boot must be lifted off the face of this country.

None of this is going to be easy. But if we are to have any chance, it will be because the ultimate leaders, the citizenry of this country, pilot the battle to save lives and livelihoods again. May that day come, with all the fierce urgency of now.

If you like what you have just read, subscribe to the Daily Friend