Baby boomers in the Western world – those born between 1944 and 1964 – have long been considered the ‘lucky generation’.

They were considered ‘lucky’ in the sense that they were born of parents who had survived the Second World War and, as they were growing up, enjoyed the material benefits of rising economies and wealth-creation in most parts of the world, especially in the developed world.

They entered the working world 20 or so years later when there was a rising demand for office workers – no more hours spent in sweatshop-conditions on a factory floor –with labour unions to defend and improve their rights and defined contribution pension benefits, which guaranteed a certain income for life.

South African middle and upper-classes enjoyed the same privilege, which was further enhanced by racial laws excluding people of colour from the same benefits.

At the same time, the country was booming way beyond expectations on the back of the discovery of gold in the Free State in the Fifties, the massive industrialisation stimulated by international sanctions, and other economic backwinds during the 70s. All these things combined to create a very prosperous demographic grouping of middle-class South Africans, building assets and generally looking ahead to a ‘carefree retirement’ which entailed endless rounds of golf, global travelling and holdings hands as the sun set on another perfect day. Well, that at least was the way the advertising brochures had it.

Many well-off newly retired people traded in their large family home for well-equipped retirement villages, where apartments cost substantially more than the larger property.

Was a very happy place to be

And for many middle-class people, until around 2010/15 or thereabout, such a lifestyle was eminently affordable. An ever-rising local stock market over four or five decades boosted first by gold, then platinum, iron ore and minerals, then the retail boom/listed property share boom in the early years of the current century, meant this was a very happy place to be.

So much so that, according to research done by Swiss Bank Credit Suisse, the JSE was one of the top three global stock markets in the world over a period of more than 100 years until 2011. Its seminal study, titled The Triumph of the Optimists, showed that the JSE alongside the Australian and United States stock markets delivered over time an annual compound growth of 7% in dollar terms.

Such outstanding long-term growth rates were also a major boost for the local retirement and asset management industry, which grew enormously, to such an extent that the South African retirement fund is the 8th largest retirement fund in the world, punching way above its weight.

What could go wrong? Well, something changed from around 2010.

At first the changes were small, almost imperceptible, like the sudden change in the wind just before a massive gale hits. To begin with, the under-performance of the JSE relative to world markets was one quarter, then two, and then one year which became two, and so on. I started calling out this underperformance on the platforms I frequented, on social media, finance websites and on radio.

Breaking the cardinal rule

I soon earned myself the monikers ‘Dr. Doom’ and ‘Mr. Negative’ and, worst of all, was described as someone who was unpatriotic and disloyal to his country for pointing out these developments. It was as if I was breaking the cardinal rule of the Sicilian Mafia, ‘omerta’, the pledge of silence. Speak out of the group and that is the end of you, punishable by going for a swim with concrete shoes. That’s how bad it got at one stage.

And, every time, the asset management sector’s reaction was, ‘don’t worry, it will revert to mean’. But one year became three, then five, then seven, until today, 10 years later, when the JSE has massively under-performed not only the developed world markets, but also against its peers in the emerging market space.

Furthermore, over the past five years, the JSE has barely registered any growth, which – together with a wide range of investment portfolios linked to the JSE in the form of pension-, provident- preservation- and retirement annuity funds – have all shown the same lack of growth.

But more telling was the reaction from my fellow colleagues in the investment advisory industry, who accused me of fear-mongering and causing panic for some unknown ulterior motive. Has speaking the truth now become a crime?

It was very hard for any commentator on South African financial markets not to point to the structural damage done to the country’s long-term growth prospects by a toxic combination of rampant state looting, policy confusion, inertia, business-unfriendly policies and a host of other misdeeds perpetrated by the ruling African National Congress over the past five to seven years.

Foreign capital is fleeing our market (over R600 billion since 2013) and is still doing so to this day.

Local investors – either out of ignorance or a misguided loyalty to local financial investment companies – are paying a heavy price today.

A very conservative calculation

In fact, based on a very conservative calculation (comparing long-term investment returns of 5% in real terms over many decades), the current value of South Africa’s retirement pot is down about 25-30% compared to where it could have been, theoretically, had the JSE kept on growing at the same long-term rate. This is true for all kinds of retirement funds, including pension/provident funds, preservation funds and retirement annuity funds.

The outcomes could also have been better had fund managers been allowed a higher exposure to the booming stock markets of the world, particularly the US market.

Our business is now totally overrun on a daily basis with disgruntled investors in one or a combination of the above products, which have shown no growth in real terms and in many case no growth in nominal terms.

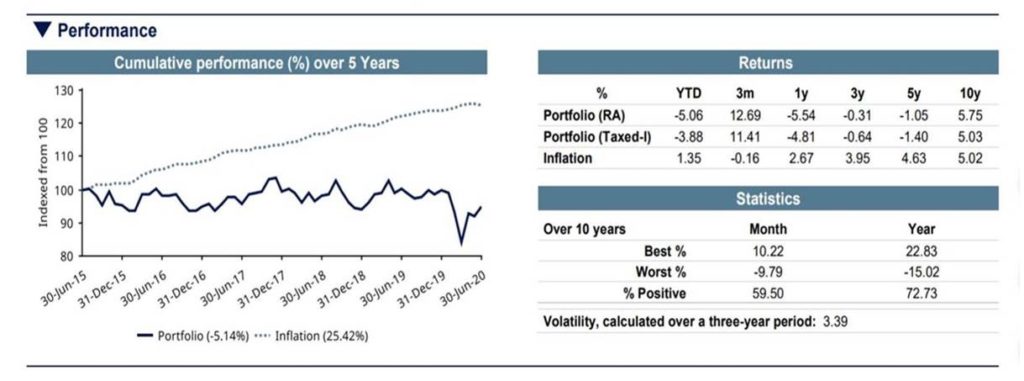

We have also – as the chart below shows – come across RA’s that have actually lost you money over a five-year period. And if you don’t believe my figures of a 25-30% deficit on pension funds, see here the figures from one of South Africa’s three largest investment companies. This particular insurance company cannot be accused of hiding the truth. It’s hiding here in plain sight for all to see!

‘Honey, I found where our retirement funds are going to!’

And that was before the Covid-19 crisis hit the world and hit the South African economy even harder.

Perhaps this particular fund (a large one, nevertheless), just had a lousy fund manager and we should perhaps have a look at averages instead.

In the chart below are the average returns for the various asset classes on the JSE compared to the returns of global assets, both in rands and dollars.

As one can see, the ALSI (All Share Index) has not produced real returns after inflation over five years, nor did listed property. Only bonds and cash managed to get its nose in front.

The main cause for this under-performance in retirement funds is what is known as Regulation 28 of the Pensions Act which, among other things, limits the percentage that fund managers/investment advisors can invest in offshore markets. The maximum has been pegged at a mere 30% of total assets. While another 10% may be invested into African bourses, this did not help in any way, as African bourses have done worse than the local JSE.

The JSE – which was called ‘increasingly irrelevant’ by market commentator Alec Hogg the other day – has had a torrid five years and was not only one of the worst-performing markets in the world, but it made no money in real terms in over seven (and soon to be 10) years in USD terms.

Considered ‘alarmist’

Despite these shocking numbers, there is very little discussion in the mainstream media about this growing catastrophe. It is considered ‘alarmist’ to be discussing this, while other advisors have accused me of fear-mongering and causing panic for an ulterior reason. I feel like the lookout on board the Titanic who, after noticing the looming iceberg, goes running through the ship trying to warn passengers, only to be told he is upsetting the first-class passengers playing bingo!

In addition, many self-employed business people always considered their profitable business as their biggest asset, to be sold as retirement approached in order to fund the long-planned retirement nirvana. For many, if not most, those deals have disappeared in a puff of smoke.

I know of countless such deals that were vaporized within days after Covid-19 hit. Instead of talking to the dealmakers, such business people are now talking to business rescuers.

So your pension is stuffed, your business has gone under and your other two major assets which could have come to the rescue – residential property and or cash – have also taken body blows.

Residential property prices and concomitant rental yields have been deflating for over 12 years now, but the current pandemic and lockdown has accelerated this process, compressed into a brutal few weeks, instead of years, as it normally takes.

No real growth

The other day I bumped into the leading estate agent in the area where I live, and, as we always do, we talked about property and the property market. It transpired from this short conversation that the agent is selling the same properties he sold five years and more ago for the same prices today. In other words, no real growth in nominal prices, which means a decline of about 25-30% in real terms.

Yet, read any press release from the leading estate agencies and one would swear that the property market is in full bloom. This may be true in the lower-end of the market, below R1m and where transfer duties have been scrapped, but in the middle to upper reaches of the residential property market, prices have tumbled by between 10% and 50%, depending on the area and who you believe.

In short, all over the country in untold households, savers/investors and wannabee retirees are finding it hard to keep the bile down while looking at their final retirement numbers, trying to reconcile that with their income requirements during retirement. Retirement dreams are well and truly f#cked.

With no capital growth in over five years, residential property in the doldrums and with interest rates at 50-year lows, that carefree retirement has been turned into an unending financial nightmare for thousands of people.

Retirement could not have come at a worse time. Or, to borrow from Kenny Rogers’s hit song, ‘You picked a fine time to retire, Lucille.’

[Picture: Susanne Pälmer from Pixabay]

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR

If you like what you have just read, subscribe to the Daily Friend