In the wake of the total breakdown of law in order in KwaZulu-Natal and parts of Gauteng in July, a new survey finds strong and growing support for the idea of an independent Cape of Good Hope.

The Cape Independence Advocacy Group (CIAG) yesterday released the results of a new survey which shows that in just one short year there has been a marked increase in support for the idea of independence among residents of the Western Cape.

An outright majority of adult voters (58%) now supports calling a referendum on independence. Coincidently (or not), the Democratic Alliance (DA) has recently tabled a private members’ bill in Parliament that would give effect to provincial premiers’ constitutional right to call referendums.

Pending the passing of that bill, pressure is certainly growing on Alan Winde, the premier of the Western Cape, to call a referendum on independence for the province.

I am firmly convinced that independence would be very good for the people of the Western Cape, no matter what their socio-economic background. Given friendly relations and free trade with the rest of South Africa, it would be entirely feasible to establish the Cape of Good Hope as an independent country.

The arguments in favour of Western Cape secession are very strong indeed, as I have written before. However, even though the time for an independence campaign is undoubtedly right, there are reasons to doubt whether it could be successful.

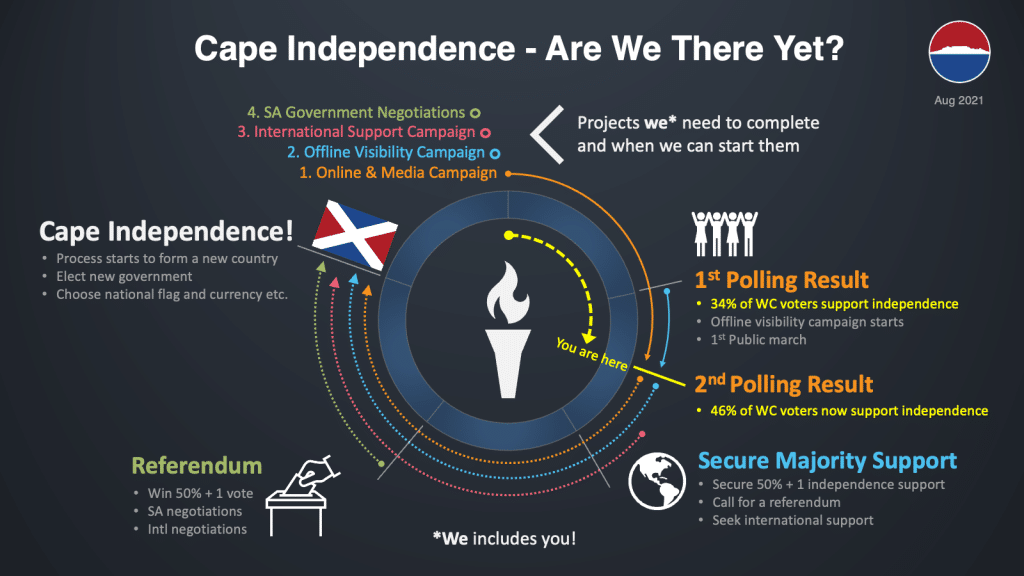

The CIAG has presented a neat little infographic showing the road to independence, but it is far from clear how realistic its vision is. More on that later.

Survey results

Support for independence among voting adults grew from 34% in 2020 to 46% in 2021, while support for calling a refendum on independence increased from 47% to 58%.

Among Freedom Front Plus voters, support for a referendum was 90%, while almost two thirds of Democratic Alliance voters supported it. Even EFF voters were in favour of a referendum, although a large majority were not in favour of independence itself. Among ANC members, a surprising 37% favoured a referendum, although fewer than 20% supported independence.

Disaggregated by race, the survey found 50% of coloured people, 22% of black people, and 64% of white people supported independence. In the case of white people, this reflected no change on the 2020 results, but among coloured people this was a significant increase from 39%, and among black people from 16%.

(I rounded these statistics. With an error margin of 4%, decimals merely ruin the readability of the numbers.)

Among all three races (Indians being too small a minority in the Western Cape to reach statistical significance in the sample), support for a referendum was higher than support for independence.

Sixty-five percent of coloured people, 37% of black people and 77% of white people favoured calling a referendum. Again, the position of white people remained largely unchanged from 2020, but there was a large increase from 44% among coloured people, and a small increase from 34% among black people.

Racial disparity

That independence is an unpopular idea among black people is reflected in their answers to the question of whether they believed their quality of life would improve in an independent Western Cape. Only 15% said yes, while 77% believed it would worsen.

This contrasts sharply with the views of coloured people, of whom 58% thought their quality of life would improve, and 75% of whites who believed the same thing.

There was much more unanimity about whether South Africa was going in the right or wrong direction. Among coloured, black and white people, 88%, 88% and 90%, respectively, agreed that it was going in the wrong direction. That was a significant jump from the 75%, 65% and 82%, respectively, recorded last year. Even among ANC members, 80% now believed the country was headed in the wrong direction, up from 57% last year.

No doubt the last year’s Covid lockdowns and the violent unrest in parts of the country contributed to this swing.

In other results, about three in four voters believed the Western Cape was better governed than the rest of the country, and the same proportion thought provincial governments should be given more power to choose their own policies.

The low support for independence among black residents of the Western Cape is a matter of some concern. If the independence movement wants to establish broad legitimacy, then its overt commitment to non-racialism ought to be reflected in its support base.

It might seem easy to make the argument that black ANC voters are simply wrong about their prospects in an independent Western Cape, but it may also be hard to sway a population that is heavily dependent upon the national government for patronage, jobs and social security.

Civil war

Helen Zille, the DA’s Federal Council chairperson, has made it explicit in an interview with David Ansara of the Centre for Risk Analysis that the DA does not support Western Cape secession.

This may in part be because the DA is loath to be seen as seditious. The Constitution of South Africa, after all, declares the country to be a unitary republic, which requires ‘[a]ll spheres of government and all organs of state within each sphere [to] preserve the peace, national unity and the indivisibility of the Republic’.

She also admits that the DA fears independence-minded splinter parties might draw support away from the DA, thereby imperilling its electoral majority in the Western Cape.

She does support a much greater degree of federalism and provincial autonomy, and is of the view that the Constitution, as it was negotiated at the Congress for a Democratic South Africa (CODESA), was not nearly federal enough in character.

A federation is a system of government in which powers devolve to constituent states or provinces, except for those explicitly assigned to the national government in a founding constitution. The United States of America is the archetypal modern federation.

South Africa’s system of co-operative governance is a very weak version of federalism, in which the national government retains almost all significant powers and duties, notably that of taxation, and even though some less significant powers are devolved to the provinces, they remain largely dependent on national government for funding and many basic services.

Zille said that Cape independence is ‘not realistic politics’. It can only happen, she argues, if one can get the support of a significant majority in both Parliament and the National Council of Provinces, since independence can only be granted by the national government.

The only other way to achieve Cape independence, she says, is civil war.

International support

The roadmap plotted by the CIAG is based on the view that the Western Cape would not need the permission of the national government to secede. That view makes a few big assumptions.

First, they would have to garner significant international support for the independence movement. That overwhelming support would be forthcoming does not seem immediately obvious.

Then, they would present the result of a referendum as a fait accompli to the national government, on the assumption that it would merely need to negotiate the terms of the secession.

It is unclear what they would do if the ANC simply turned around and said, ‘That’s nice, but no.’

It seems unlikely that international pressure would be strong enough to convince the ANC government to consider itself bound by the outcome of a referendum. It also would not bind itself to the outcome of a referendum in advance.

This, then, leaves Zille’s civil war as the only remaining option. Even though I and a few mates down the pub could probably defeat the SANDF in a pitched battle, I suspect support for Western Cape independence would plummet dramatically if it would take significant bloodshed to achieve it.

More federalism

Zille’s goal of greater federalism and more autonomy for provinces, especially in competencies at which the national government is failing, such as electricity provision and police services, is indeed attractive.

In agitating for greater provincial autonomy, an active and vocal independence movement may be very valuable. Even if you suppose that actual secession will not happen peacefully, the movement could place a great deal of pressure on the national government to make concessions to the provinces.

Greater autonomy for the Western Cape, within the unitary republic of South Africa, would certainly be an improvement on the status quo, and would to some extent insulate it from the failures of ANC governance at national level.

It would also serve as an example of what is possible with competent, clean government that holds liberal principles dear.

Zille says the rest of South Africa is worth fighting for, and I agree. A stronger, more autonomous Western Cape can only hasten the demise of the ANC in the other provinces, starting with the metros.

It might take time to convince voters in rural areas, with their high dependence on government grants, to kick the ANC out, but it is far from impossible, provided the Western Cape can serve as a good example that the poor in rural areas also benefit from clean, competent and liberal government.

The Cape independence movement is worth supporting, even if only as a Utopian ideal. Achieving its goal would be first prize, but to the extent that it can bring about a greater degree of federalism in South Africa, it has a valuable role to play in the country’s future even in failure.

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend