Last week’s column discussed how South Africa’s economic experience in recent years differed from that of Indonesia and Vietnam. All three are middle-income countries, but while South Africa has endured a decade of effective stagnation, Indonesia and Vietnam have grown.

This is a point picked up in a recent review of South Africa’s performance by the National Planning Commission (NPC), which asks what can be learned from these peer countries.

One important realisation in drawing lessons from the experiences of Vietnam and Indonesia is that they exist in their own unique contexts; these may not be replicable. Two obvious factors need to be foregrounded.

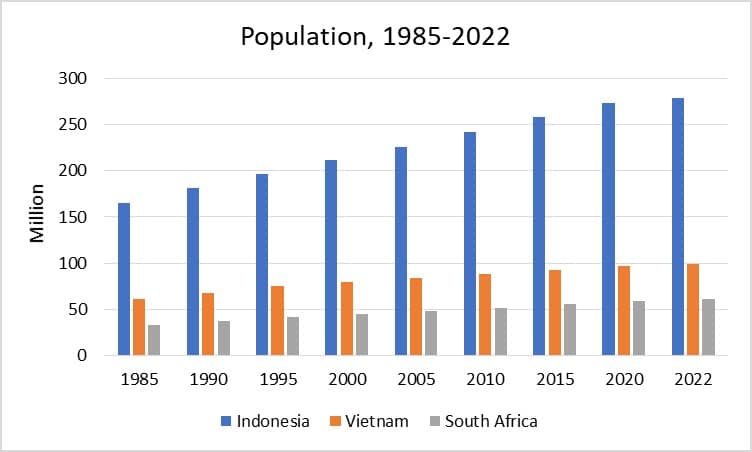

The first is demography. Indonesia and Vietnam both have significantly larger populations than South Africa. The World Population Review shows how the population of Indonesia – the fourth most populous country in the world – has risen from close to 165 million in 1985 to in excess of 279 million today. Vietnam’s growth has been lower – from around 61 million in 1985 to some 99 million now – but its population is still significantly larger than South Africa’s. Indeed, from a little under 33 million in 1985, South Africa’s population is now approaching 61 million. This is not small by any measure, but it means that South Africa started the period with a population only half that of Vietnam, and now has a population roughly equivalent to that of Vietnam in 1985.

A large population can be an asset for development. It can mean a large workforce and a large market, making it an important attraction to investors and trade partners – depending of course on a number of subsidiary factors, such as the size of the working-age population, the size and growth of the middle class, the skills profile and so on.

Second, the East and Southeast Asian regions are economically dynamic ones. Indonesia and Vietnam have the good fortune of being adjacent to large and growing economies, and sitting astride important trade routes. More than half of the trade conducted in this part of the world is conducted between countries of the region.

The southern African region (and the continent as a whole), by contrast, simply does not as yet provide the same opportunities. South Africa’s prime markets are geographically distant.

The table below, drawn from the Observatory of Economic Complexity, shows the percentage of trade conducted by Indonesia, Vietnam and South Africa with their neighbouring regions. For Indonesia and Vietnam, these figures include East and Southeast Asia. For South Africa, they represent Africa as a whole.

Indonesia and Vietnam conduct well over half their trade with the region. For Vietnam, imports from regional partners are especially important. South Africa by contrast does not manage a quarter of its total trade with the entire African continent – and of the proportions shown here, two thirds of imports and over three quarters of exports take place within the Southern African Development Community.

It is also important to recognise that the development paths of Vietnam and Indonesia have differed from each other. Any analysis must keep this in mind; lessons are important, but experience is in some way unique. Nevertheless, both Indonesia and Vietnam emerged from periods of severe economic retardation, and have to an extent overcome them.

Indonesia

Indonesia has had an uneven economic history. In the early 1960s, the ideological and geopolitical fixations of its iconic post-independence leader Sukarno were matched by an indifference to economic management, and the substitution of slogans and symbols for achievement. Inflation reached triple digits, economic output collapsed, and there was widespread poverty and hunger – this was represented for global audiences in Peter Wier’s 1982 movie The Year of Living Dangerously.

Following Sukarno’s ouster in 1967, the government of the so-called New Order liberalised economically (although maintaining a highly repressive political regime) under the influence of US-educated technocrats, the so-called Berkeley Mafia. Indonesia opened up to imports, brought inflation under control and had success in attracting investment. It also sought to put in place enablers, such as solid infrastructure. Its progress was helped along by foreign aid (Cold War politics at play), and the rising oil price in the 1970s.

From the 1970s, manufacturing expanded, as cheap, abundant labour along with the more open economy made it an attractive production site for exports – and for products for a growing consumer market.

Indonesia has, however, been roiled by difficulties. In the 1980s, its economic progress came under pressure as the oil price fell, and corruption – often linked to prominent, politically connected families – took hold. A new round of market-friendly reforms was introduced, and once again, investment and growth recovered.

Indonesia’s economic performance had also left it overexposed to dollar loans; along with hollowed-out institutions and voracious patronage networks, the Asian financial crisis hit it hard. Nevertheless, following this episode, Indonesia managed to maintain a reasonable level of growth.

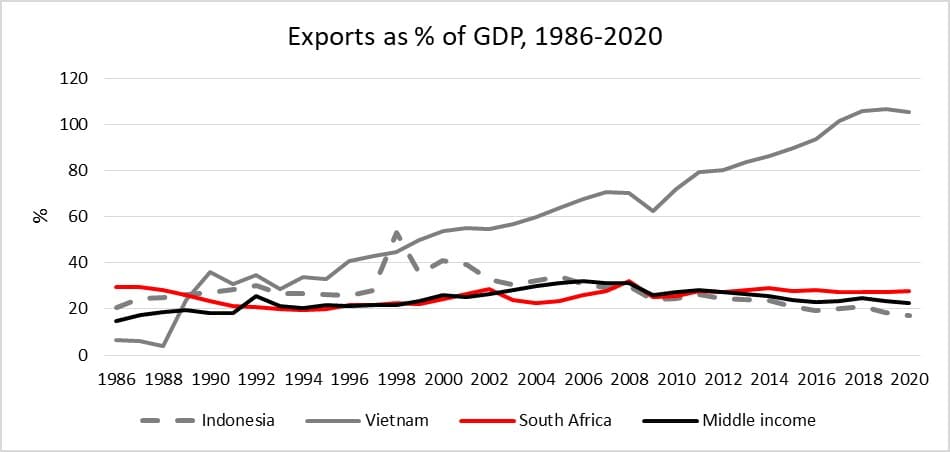

Interestingly, in recent years, it is generally recognised that its growth has become less dependent on exports and foreign trade – a very important source of its early advances – than on domestic consumption. A 2012 report by McKinsey addresses this, noting that Indonesia is not a ‘typical Asian manufacturing exporter driven by its rich endowments of natural resources’; rather, manufacturing is outdone by services, while the size and importance of its national market far exceeds that of its exports. Exports accounted for only around 17% of GDP in 2020. With its extensive population, rising urbanisation and growing middle class, this is a pathway that Indonesia is in a position to take.

Indonesia’s aspirations are to move beyond its current middle-income status to high-income status, and to be one of the world’s top five economies by 2045. This will require upgrading of human resources and physical and digital infrastructure – endeavours in which Indonesia has made some progress. Infrastructure has expanded significantly over the past two decades. One measure of this has been the Global Competitiveness Index (GCI) scoring of Indonesia’s infrastructure: in 2006/07, this was rated 2.7 (on a scale of 1 to 7, with 7 being best); this had climbed to 4.5 in 2017/18.

Education has been significantly expanded in recent decades. This helps to explain a rise in productivity – a factor remarked on by a number of analyses – which has been noted across the economy.

Productivity gains have, however, been unevenly distributed across the economy, and on the whole they have been insufficient at present to support the transition to a high-income, innovation-driven economy. This remains a constraint to its ambitions: in the field of education, Indonesia performs indifferently on global benchmarking tests such as the OECD’s Program for International Student Assessment (PISA), while the GCI reflects concerns about weakness in the country’s technological readiness.

Nevertheless, Indonesia can claim some success in encouraging the digital economy. It is home to some 2 300 tech start-ups, among which 12 are regarded as unicorns (worth more than $1 billion). Arsjad Rasjid, the chairman of the Indonesian Chamber of Commerce and Industry, said earlier this year that the country’s digital economy was on track to be valued at $146 billion by 2025.

Vietnam

Vietnam’s economic ascent has been – arguably – even more remarkable than Indonesia’s. In the mid-1980s, its economy and infrastructure remained devastated by two sets of wars fought on its territory. It was suffering inflation of some 700% annually and was kept afloat fiscally by subsidies from the Soviet Union.

Its turnaround took place with the adoption of the Đổi Mới programme – Đổi Mới is roughly translated as ‘renovation’ – which meant an effective abandonment of the pre-existing communist dogma. Rather like the Indonesian New Order, this combined economic liberalisation with tight political control. Agriculture was an immediate focus, and these reforms abolished unwieldy collectives, encouraging private peasant cultivation on long-term leases; price controls were relaxed and the farmers were allowed to trade for a profit. Trade liberalisation was pursued, the currency devalued, state companies closed down, streamlined or privatised. Private businesses were encouraged. And so on.

A law on foreign investment in 1987 opened the market to foreign enterprises. A large low-wage labour force was enticing for investors – and as China’s labour costs have risen, so has this aspect of Vietnam’s offering become even more competitive, at least for the present.

Vietnamese themselves took advantage of the new opportunities. Aside from migration to the country’s burgeoning industrial centres to take up employment – helping shift the economy fundamentally out of it agrarian roots – there was a flourishing of private enterprise. The American satirist (and 1960s anti-Vietnam War protestor), the late PJ O’Rourke, recounted that during a visit to the country in 1992, there was a vibrant entrepreneurial energy, with the phrase ‘joint venture’ featuring in the English vocabulary of every Vietnamese he spoke to. He titled his essay: To Hell with Everything, let’s get Rich. By the late 1990s, some 30 000 private businesses were reported to have been established.

Central to Vietnam’s economic strategy has been concluding trade agreements. In short order, it joined the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and the ASEAN Free Trade Agreements, concluded bilateral trade agreements with the United States, Japan and the EU, and later joined the World Trade Organisation. Not only did these give Vietnamese products access to foreign markets for low-cost manufactured goods (currently, over a quarter of Vietnamese exports are destined for the United States), but by enabling the import of sophisticated machinery and inputs, they were able to push Vietnam up the manufacturing value chain.

The importance of trade is underlined by looking at the differences in the volume of trade. In 2020, according to the OEC, Vietnam’s imports were worth $270 billion and its exports $300 billion.

Equally revealing is the extent of exports as a proportion of GDP, which underlines the centrality of trade to Vietnam’s progress. The graph below shows the rapid growth of Vietnamese exports since the 1980s, and they now exceed 100% of the country’s GDP.

Economists Sebastian Eckardt, Deepak Mishra and Viet Tuan Dinh put it succinctly in a commentary on Vietnam’s manufacturing sector: ‘Trade policy has arguably been the most important industrial policy for Vietnam. With Singapore, it shares the top spot in East Asia of being a member for [sic] bilateral and multilateral free trade agreements.’

Besides this, and in common with Indonesia (if possibly to a greater effect), Vietnam put a great deal of emphasis on human development and infrastructural expansion. Electricity provision is often cited as a major achievement, embodying a combination of prudent state management, development assistance and private sector involvement: in the mid-1980s, only 9% of households had access to electricity; this is now universal. Indeed, concerns exist now that Vietnam is using its power supply inefficiently.

As the reforms initiated by Đổi Mới took effect, complementary measures were taken to ensure that Vietnam’s people were able to make use of the opportunities on offer. Education and training programmes – focusing both on school children and on those in the workforce – were put in place to upgrade the country’s skills profile. This appears to have borne fruit. Vietnam’s primary school completion rate is now near universal, and by one important international measure, the PISA rankings, Vietnamese students have performed exceptionally well. In the 2015 round, they ranked 8th highest in the world in science, beating many far more advanced and better resourced economies. In reading and mathematics, Vietnamese students performed at around the OECD average, again, performing better than their peers elsewhere. In mathematics, Vietnam outperforms both the United States and the United Kingdom.

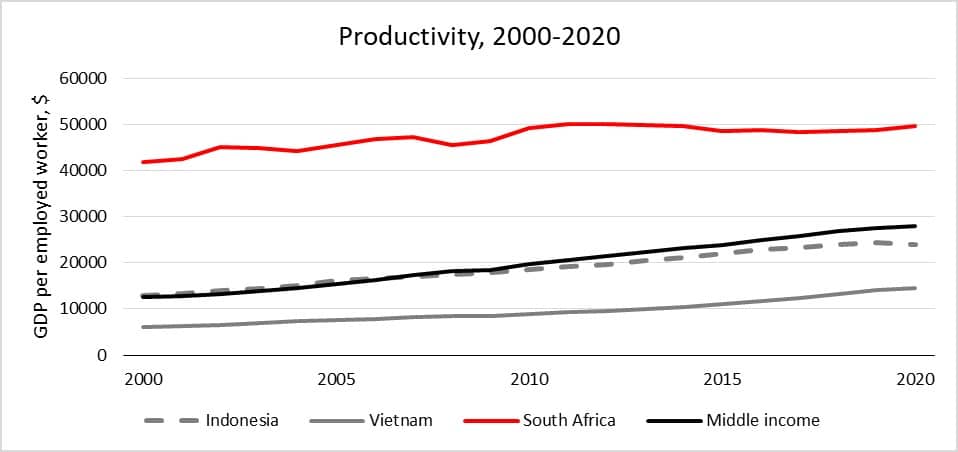

Hence also, the rising productivity of Vietnamese workers (illustrated above) and the move to higher-tech and increased value-added manufacturing.

Vietnam intends to elevate itself to high-income status by 2045 – interestingly, a target year it shares with Indonesia. This would require sustaining an annual growth rate of some 5% until that point. Based on its record, this seems eminently within reach. The country does, however, face challenges in this aspiration. These include a workforce that is now aging, rising global protectionist sentiment and weak institutions. To counter this, it will be able to look increasingly to domestic consumption, and has by all accounts created the foundations of a skilled workforce, which could drive the necessary productivity gains. To move up the value chain will require not only replicating the successes of the past three decades, but also learning to do business in a more efficient and innovative way.

What is the takeaway? Eckardt, Mishra and Dinh remark:

Vietnam has achieved its success the hard way. First, it has embraced trade liberalization with gusto. Second, it has complemented external liberalization with domestic reforms through deregulation and lowering the cost of doing business. Finally, Vietnam has invested heavily in human and physical capital, predominantly through public investments. These lessons – global integration, domestic liberalization, and investing in people and infrastructure – while not new, need reiteration in the wake of rising economic nationalism and anti-globalization sentiments.

South Africa falls behind

Indonesia and Vietnam have pursued growth strategies with both similarities and differences and neither has been without difficulties. Neither country can expect a problem-free path into the future. And there are elements South Africa should not wish to emulate. Vietnam, for example, remains a highly authoritarian state that tolerates little dissent. Moreover, in certain respects – such as productivity – South Africa retains a sizable advantage. Yet the degree of economic progress – call it the direction of play – has been positive overall for their economies and for the wellbeing of their respective peoples. Consider this: the growth in productivity, as shown above, was some 86% in Indonesia, 139% in Vietnam, 123% across the middle-income group, but only 19% in South Africa. And on balance, these countries seem to be making that progress at a much more rapid pace and a more ‘transformative’ manner than is the case in South Africa.

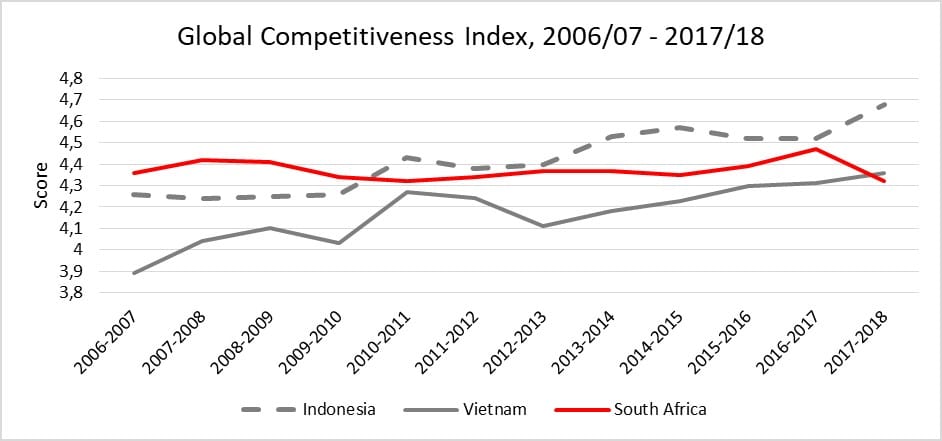

The Global Competitiveness Index helps to show this. The GCI has long been a somewhat contentious measure, but it does provide a comparative set of data from experts as to how conducive to business and attractive to business the countries covered are. The table below plots the scores of the three countries, as shown in their reports from 2006/07 to 2017/18; countries are rated on a scale of one to seven, with higher numbers signifying greater competitiveness. (A change in methodology in subsequent reports makes it difficult to provide comparable data for more recent years.)

As is evident, both Indonesia and Vietnam have seen their scores increase over time. South Africa, by contrast, has been rather flat, and by the end of this period, it was not only at its lowest point, but had fallen behind its peers. (Note though that South Africa recovered in the subsequent editions, with explicit mention being made of the change from President Zuma’s administration to that of President Ramaphosa.)

GCI rankings make for a somewhat more nuanced picture (note that a lower number here means a ‘better’ score), but the implication is that South Africa has been losing a relative advantage in its competitiveness.

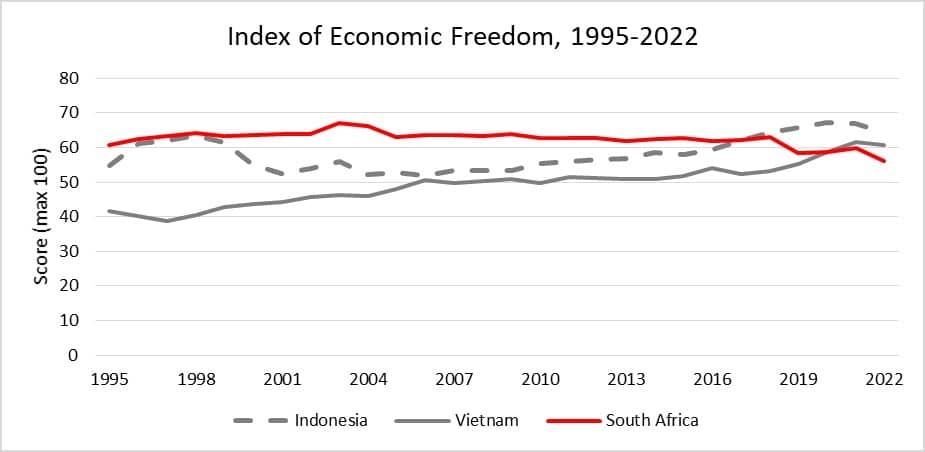

A similar message is conveyed by the Index of Economic Freedom, produced by the American Heritage Foundation.

Vietnam and Indonesia (the latter with declines around the time of and following the Asian Financial Crisis) have tended towards greater economic freedom. South Africa, by contrast, exhibited some tendency towards economic freedom in the 1990s and 2000s, then declined, flatlined, and recently has tended away from it. At present, both Indonesia and Vietnam are classified by the index as Mostly Free. South Africa, by contrast, is Mostly Unfree.

What can South Africa learn from this?

One obvious lesson is that globalisation and trade are – on balance – good things, particularly for small and mid-sized economies which cannot depend on their own consumer base to drive growth indefinitely. South Africa lacks an Indonesia-sized market. Regional integration across the subcontinent and across Africa as a whole offer opportunities for South Africa’s economy. This needs to be pursued actively, in a conscious attempt to build profitable regional markets.

At the same time, South Africa cannot afford to ignore its existing trade relationships. These are valuable and should be nurtured and protected, irrespective of the identity and geopolitical posture of the trading partner.

One important element of this is that as much as South Africa benefits from its exports, it needs imports. If indeed it is to expand its manufacturing economy, it will need to fit into global value chains. Its infrastructural deficiencies and sheer geographical distance from many of the world’s markets already make this a tough sell for South Africa. A protectionist agenda – something that the Department of Trade and industry seems to be wedded to, with increasing intensity – is likely to be counterproductive. Attempting to protect local steel manufacturing will ramp up the costs of steel inputs, which can cheaply be sourced elsewhere – to the detriment of those local manufacturing businesses that government policy is supposedly committed to promoting.

Closely related to an embrace of globalisation is the embrace of domestic policy reform. This is a nebulous concept certainly, but an important one. Competitive, growing economies try to facilitate doing business, making investments and creating employment. Reducing the complexities of doing so, and providing an environment in which it is attractive to do so, should be a basic principle of governance. Economic freedom – which does not imply wholesale deregulation, but recognises the importance of providing latitude and flexibility for businesses to operate – counts greatly. This finds some official acknowledgment: successive governments (going back to the 1980s, and encompassing each post-1994 administration) have declared themselves committed to removing undue administrative burdens, particularly from small business. But whatever has been achieved in this respect – and it is far from substantial – has been undone by rafts of other intrusive and ultimately destructive legislation.

Thus, property rights have come under threat through a wholly misguided Expropriation without Compensation drive. A more recent example is the pending amendment to the Employment Equity Act, which would see the minister imposing sectoral racial quotas. The consequences of these policies will more than negate whatever contribution a meagre financial incentive or a policy statement might make. A good start would be to simply step back from some of the proposed policy interventions.

Dr Mark Mobius, then of Franklin Templeton Investments, commented some years back: ‘They’ve got to make South Africa a much more attractive place for investment… I’m not only talking about foreign investment. I’m talking about local investment.’

But policy will not be sufficient. Both Indonesia and Vietnam have shown the need for skills and education to sustain growth, and crucially to move into more advanced activities. South Africa finds itself in the difficult position of having an economy that has already reached a high degree of sophistication – along with a large pool of poorly skilled people AND a skills shortage. Education efforts over the years have failed to produce their intended results.

Vietnam’s success has been the subject of considerable interest, since it is not obviously driven by spending. Some observers have suggested that it might represent a peculiar socio-cultural orientation, which would make replication very difficult.

In infrastructure terms, the government’s prioritisation makes sense – provided it can be delivered efficiently and does address the various blockages. Power shortages have been a major choke on South Africa’s economy for well over a decade. The failure to address this issue – governance failings at Eskom, hostility to private sector provision, and so on – have cost the country immensely. It is worth noting that the reform initiatives that are now being contemplated in South Africa are mirrored to what Vietnam undertook close to two decades ago.

Logistics networks such as ports, roads and railways, properly maintained, will also be critical if South Africa is to take advantage of today’s trade opportunities. This is equally the case for maintaining its current trade relationships (keeping South African exports competitive), and in expanding trade across the region and the continent.

Institutions matter. Governance systems are critical for organising life and for creating the ecosystem within which development takes place. In various ways, Indonesia and Vietnam provide both recommendations and warnings. Neither country is an avatar of what might be called ‘good governance’. Both countries actually rank below South Africa on Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index. What they exhibit is more a case of ‘good enough governance’: broadly sufficient to respond to the needs of the country and to facilitate the functioning of the economy in relation to the opportunities available to it.

Indonesia, in particular, showed the consequences of widespread corruption in its various economic crises: corruption had done great damage to the resilience of precisely those institutions that might have helped manage the crises. One study of corruption in Indonesia – Combating Corruption in Indonesia, published in 2003 by the World Bank – made the following cautionary comment:

Why did Suharto’s New Order succeed in delivering high levels of economic growth and substantial poverty reduction despite high levels of corruption? The answer is in two parts. The first is that the regime was careful to ensure that the scale of corruption did not deter investment and economic activity and kill the goose that laid the golden egg, requiring extraordinarily good management and restraint, neither of which lasted into the 1990s when greed began to assert itself. The second is that this success is overstated since it came at a high cost in terms of weak and corrupt institutions, severe public indebtedness through mismanagement of the financial sector, the rapid depletion of Indonesia’s natural resources, and a culture of favours and corruption in the business elite.

This issue remains a pressing problem in Indonesia today; and there is a danger that corruption and the politicisation of South Africa’s institutions could lead to such an outcome.

Resilient, independent institutions will become increasingly important as economies become more sophisticated. Whether Indonesia and Vietnam are in fact able to make the transition to high-income economies will depend in no small measure on whether they can build the institutions to manage the transition and whether those institutions can deliver on their mandates. The degradation in South Africa’s institutions constitutes an immediate problem and undermines future prospects. The NPC itself has noted: ‘A significant challenge and contradiction that goes against the developmental state aspiration of South Africa identified is the rejection of meritocracy in the country’s public service.’

Finally, both Indonesia and Vietnam demonstrate the importance of political choices. Economic take-off would have been impossible in either country without a government commitment to reverse course on previous policy stances. For Vietnam, this was particularly profound: it required the ruling Communist Party effectively to repudiate its ideological orientation, and to cooperate with erstwhile enemies. Similar shifts have occurred in China and South Korea. In a way, future development depended on overcoming history.

This may well be the most important of all lessons. It is also the one that South Africa’s ruling party has had the greatest difficulty in learning – it is quite remarkable that despite the manifest failings of the South African state, there remains a solid belief on the part of many in government and in the ruling party in the necessity of a ‘developmental state’. This is delusional (and a subject for another column). There exists a strain of almost Cold War-style geopolitical thinking that reflects a deep ambivalence (at best) towards many of South Africa’s existing trade and investment partners, something that – together with an ineffective state system – might explain why so little successful economic diplomacy is undertaken.

The NPC was correct to ask what could be learnt from the experiences of other countries. Whether these messages are heeded is a separate matter.

[Image: https://pixabay.com/photos/vietnam-me-ho-chi-saigon-twilight-4131606/]

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend