This Week in History recalls memorable and decisive events and personalities of the past.

19 October 202 BC – Second Punic War: At the Battle of Zama, Roman legions under Scipio Africanus defeat Hannibal Barca, leader of the army defending Carthage

The Second Punic War, fought between 218 BC and 201 BC, was a titanic struggle between Rome and Carthage for control of the Mediterranean world. Its outcome still casts a great shadow over the modern world.

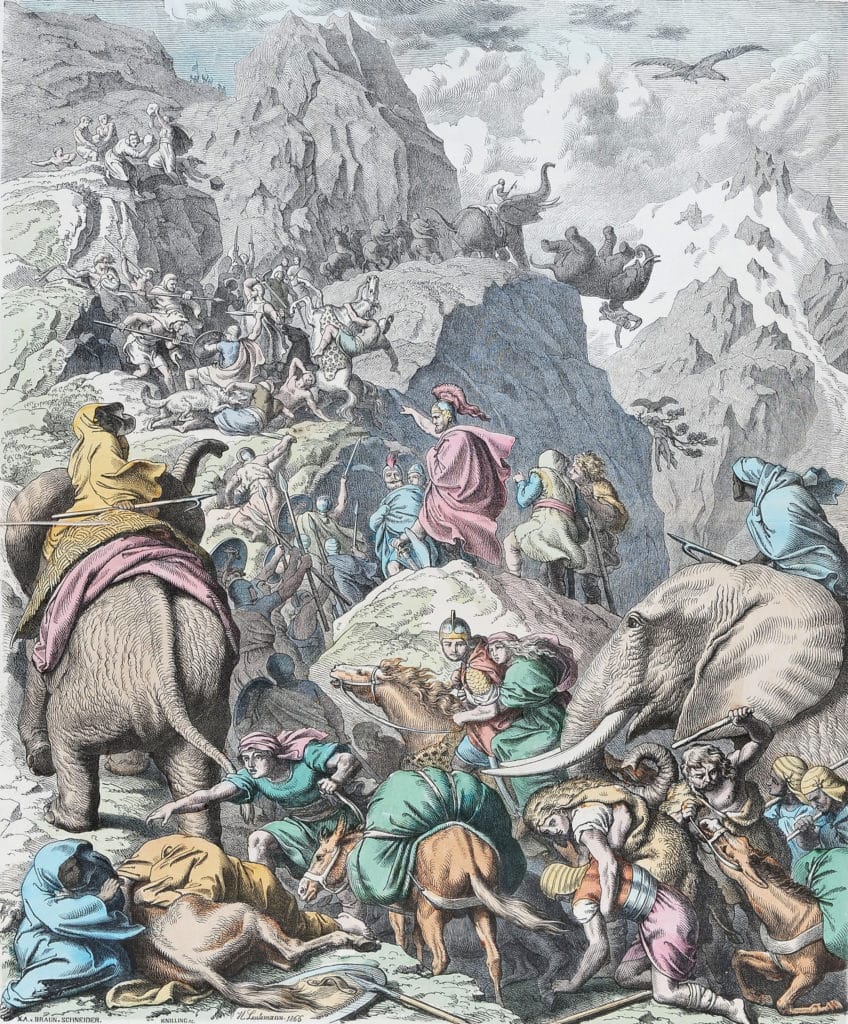

If people know anything about the Second Punic War, it’s usually about the earlier parts of the 17-year conflict. The famous Carthaginian general Hannibal marching a large army, including war elephants, over the Alps, and the following series of battles in which Hannibal displayed incredible skill and cunning in crushing multiple Roman armies, most notably when he killed 48 000 Romans at Cannae in 216 BC in the space of a few hours (which you can read about in this edition of This Week in History).

Despite his incredible victories, the Romans remained stubborn and undaunted in the face of their appalling losses, and continued the war without pausing for peace talks. After the huge Roman defeat at Cannae, many of Rome’s allies and subjects in southern Italy defected to the Carthaginian side. At this early point in its history, Rome had not yet fully assimilated the various peoples of Italy and many of the cities and tribes of Italy still had a strong non-Roman identity.

The major cities of Tarentum and Capua defected to Hannibal, as did a number of Samnite tribes. These groups added fresh troops to Hannibal’s army and provided them with supplies and money to keep fighting.

The Romans, however, had learned from their mistake of challenging Hannibal in the open and after raising a massive army of around 200 000, in part by recruiting slaves, the poor and criminals, they split this force into 10 groups, avoiding battle with Hannibal’s main force while harassing his allies.

In 215 BC, sensing Roman weakness, the Macedonians decided to attack the Romans in support of the Carthaginians. The Romans however used shrewd diplomacy to build an alliance of Greek cities against the Macedonians and fought them to a standstill.

In an attempt to wrestle Sicily from Roman control and allow Carthaginian reinforcements to flow to his army in Italy, Hannibal encouraged the Greeks of Sicily to revolt against Rome. This saw the major Greek city of Syracuse, until then a Roman ally, attack the Romans and try to throw them off Sicily in 213 BC. The Romans quickly besieged Syracuse but struggled to break in due to the cunning contraptions of the famous Greek scientist Archimedes, who was a resident of Syracuse.

In 212 BC a Carthaginian army attempted to relieve Syracuse, but ultimately failed, and the Romans broke into the city killing many of its inhabitants, including Archimedes.

The Carthaginians would have some success in Sicily, but ultimately would be crushed by the Roman armies, leaving Hannibal’s main army in Italy cut off from supply from Carthage.

Over the next few years, Hannibal would continue to crush Roman armies, but never decisively enough to gain momentum or cripple the Romans. The Romans even laid siege to the city of Capua and in 211 BC, despite multiple attempts to rescue the city by Hannibal, the Romans recaptured it, punishing it for its treachery.

Hannibal’s army slowly dwindled and he had increasingly to fight defensively against the Romans, gradually losing the ground he had gained across southern Italy. In 209 BC the Romans captured Tarentum.

Help was on the way for Hannibal: his brother Hasdrubal, following in his brother’s footsteps of a decade earlier, marched an army of 35 000 across the Alps to reinforce Hannibal. The Romans were now facing Hannibal’s still dangerous army in southern Italy and Hasdrubal’s new force in the north. Hannibal was unaware of his brother’s arrival.

The Romans, ever cunning, tricked Hannibal into thinking their full force still faced him, while marching most of their army to the north. As a result Hannibal sat in camp while Hasdrubal had his army smashed by the Roman force.

In 205 BC Hannibal’s other brother, Mago, arrived with an army in northern Italy in the hopes of supporting his brother, but was also smashed by the Romans.

While Hannibal had been rampaging around Italy beating up Roman armies, the Romans had been fighting Carthage and its allies in Spain, the place where the war had begun.

Under the command of an ambitious young Roman general, Publius Cornelius Scipio, the Romans steadily overcame the Carthaginians across Spain, finally defeating them in Spain in 205 BC.

During the entire war, the Romans had encouraged the Numidian people from modern Algeria, famous for their horsemen, and long-time allies of Carthage, to attack Carthage.

While the Carthaginians had mostly come to terms with the Numidians by 205 BC, some of the Numidian princes remained resentful of Carthage and continued to support Rome.

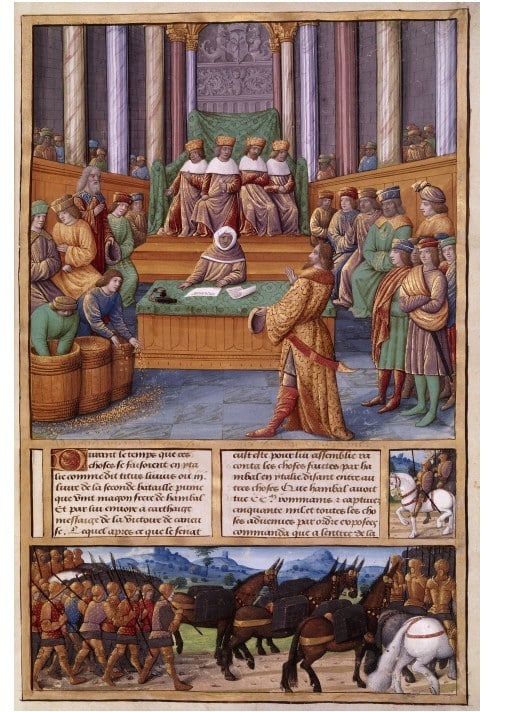

In 204 BC Scipio was given orders by the Roman Senate to travel to North Africa and end the war by attacking Carthage itself.

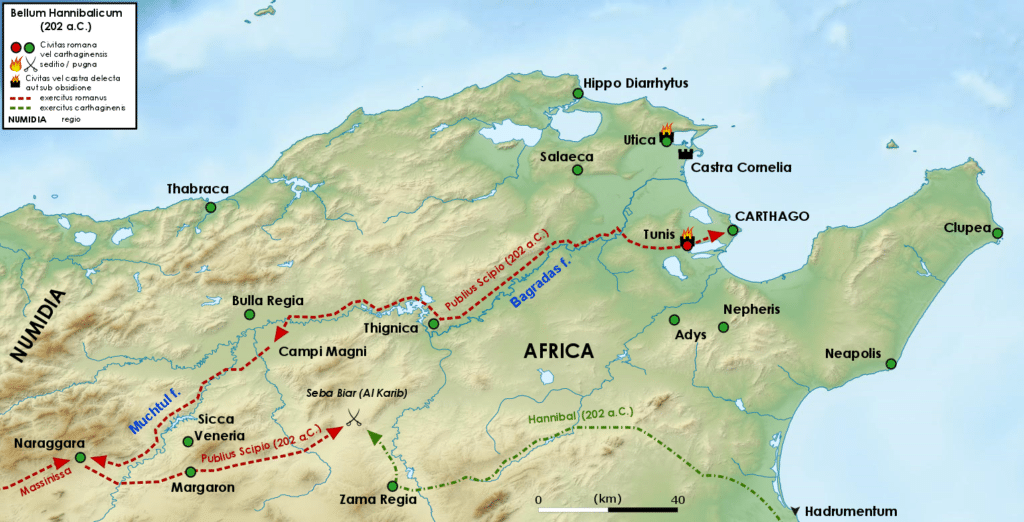

Scipio landed in North Africa, and was joined by an army of anti-Carthaginian Numidian horsemen. Scipio smashed the local Carthaginian forces and forced the Carthaginians to sue for peace. Carthage took this time to recall Hannibal from Italy.

When Hannibal arrived, the Carthaginians – nervous about the steep terms the Romans were intent on imposing on them, and now emboldened by the return of their great war hero – broke off the negotiations and attacked.

In 202 BC Hannibal faced off against the Roman army led by Scipio at a place called Zama south-west of the modern city of Tunis.

The two sides were evenly matched, with 35 100 Romans against 40 000 Carthaginians, who also had 80 war elephants.

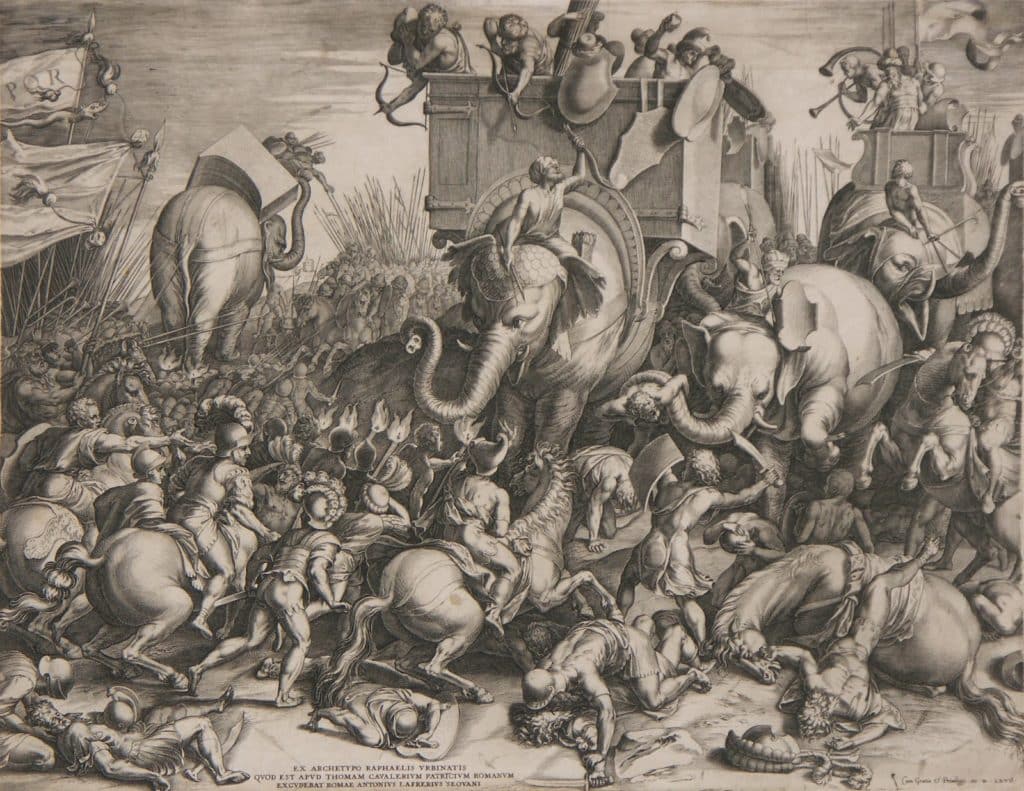

The Romans, however, blew trumpets and horns and made a huge noise when the elephants approached, thus succeeding in scaring some of the elephants who turned around and crashed into Hannibal’s left flank, disordering it. The Roman allied Numidians charged the now disordered Carthaginian flank and drove it from the field.

Hannibal started the battle by sending forward his skirmishers and elephants to break up the Roman lines, confident of the quality of his army, most of whom were experienced veterans of 16 years of fighting in Italy.

As this happened the Roman centre advanced on the Carthaginian force and met it in hand-to-hand fighting. A brutal struggle took place, with both sides taking losses.

However, the Carthaginians were attacked from behind by the Romans’ Numidian allies, who had returned from chasing the Carthaginian left flank. Attacked from behind, the Carthaginian army was slaughtered.

After the battle, Carthage surrendered. The peace terms imposed on the city bankrupted, and utterly crippled, it. From that point on it was never able to challenge Rome again. Fifty years later the Romans would attack Carthage again, and this time destroy it.

Hannibal for his part was briefly a successful civilian politician in Carthage, before local rivals and Roman pressure forced him into exile. From there on, he served as a consultant to any nation which fought Rome. In 182 BC, facing capture by Roman troops, he committed suicide.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend