The DA is punting wind and solar. Ramokgopa is punting coal. Who is right? And where is nuclear?

The electricity minister, Kgosientsho Ramokgopa, upon whose weak shoulders the recent High Court ruling that the government’s failure to prevent load shedding breached the constitution falls most heavily, appears to be largely in energy minister Gwede Mantashe’s corner on the subject of coal.

At an event in July this year, Ramokgopa railed against the so-called ‘Just Energy Transition’ and regretted that the Komati Power Station has been mothballed. If it were up to him, he said, he would restart that power station and shave one stage of loadshedding off the schedule.

I’m inclined to agree with him.

Frankly, the only reason the ANC government is considering coal decommissioning at all is because of substantial bribes paid by eco-colonialists in the West, who are trying to shift their own failure to meet climate change commitments onto developing countries.

They don’t want to take the pain, so they pay the world’s poor to take the pain on their behalf. It’s disgraceful, really.

Commission before decommissioning

Though I do not favour coal as a source of energy, mostly for reasons of pollution, it seems daft to start thinking about decommissioning coal-fired power stations before we have built enough capacity to replace them, 24/7.

South Africa’s top priority should be to recover or create enough capacity, by hook or by crook, to be able to fuel economic growth of between 5% and 10%. (The IRR Growth Strategy 2023 shows the way to rapidly return South Africa to a growth path of 5% and beyond.)

It also sticks in the craw that developing countries should not be permitted to take advantage of their own natural resources – the same natural resources the developed world relied upon to build their industrial strength – to fuel their economic development. Instead, they are being asked to act as guinea pigs for a new, untested, and expensive energy transition.

Energiewende

Countries that have gone big on renewables, such as Germany, are buttressed by the large energy markets surrounding them, and are able to rely on French nuclear power or Danish wind power when the sun doesn’t shine in Germany. Conversely, when the sun shines too brightly and the wind blows too much, they can offload their excess electricity to the interconnected grids of neighbouring countries, even if they sometimes need to pay to do so.

Despite these favourable conditions, which South Africa does not (and likely will never) enjoy, Germany’s renewable transition has given it the second most expensive electricity prices in Europe, after Denmark, which relies heavily on wind.

Developing countries need abundant and inexpensive energy in order to stimulate rapid growth. To date, abundant, inexpensive, and clean is a trifecta that remains sadly out of reach.

Attempts to interfere in the energy production of developing countries in order to hurry them along the renewables trajectory, are reckless, and deny them the opportunity to develop faster by producing energy from less expensive, more reliable, domestic sources.

Renewables in trouble

As it stands, not only does South Africa’s coal fleet perform extremely poorly, but its renewable energy build-out is in deep trouble.

‘Of the 25 renewable energy projects awarded in 2021 in bid window 5, only eight have started construction,’ writes Wikus Kruger, a specialist in energy auctions, in Daily Maverick. ‘The rest are all “under water”: priced too low to be viable.’

The Democratic Alliance (DA) usually has fairly sound proposals on energy. It recently released a three-step plan on social media. Step one is to unleash the private sector to generate electricity. Step two says green energy can help us end rolling blackouts. Step three is to incentivise the uptake of rooftop solar.

I strongly agree with the first suggestion. In fact, ‘unleash the private sector’ is the correct answer to almost every problem.

The third step is also wise, especially for homeowners and commercial buildings. It will reduce demand, which is an imperative for any and all things provided by the government, including electricity.

Obstacles

Relying on green energy to end loadshedding, however, is dubious.

There are many obstacles to reliable green energy. Grid-scale storage, which is necessary to smooth out power delivery from unreliable sources, is bleeding-edge technology that is not yet ready for prime time.

It takes anything between 10 and 50 solar or wind farms to match the nominal energy output of a single centralised coal, gas, or nuclear power station. These projects can only be built where there is a lot of wind, or a lot of sun, and many of those locations are very far from where the demand is, or even from grid connections.

Building out grid connections to connect hundreds of small and far-flung generation projects is an expensive undertaking, and grid access is a major roadblock to commissioning renewable power projects.

Despite claims that the price of solar and wind power is competitive with coal, this is only true for the price at the plant gate. It doesn’t consider the cost of grid connections, or the cost of variable output.

This is why Eskom calculates the unit cost of electricity produced by renewable independent power producers at around R2 000 per MWh, which is far less than the R7 000/MWh it costs to run diesel-fuelled open-cycle gas turbines, but far more than coal, which costs less than R500 per unit, or nuclear, which costs a mere R100/MWh. (See page 86 of its integrated report.)

Private sector

The real solution to the problem is not to prejudge what the right energy mix is, at all.

By offloading the responsibility for generation to the private sector, why should anyone care exactly how they generate it (provided that they meet technical specifications and pollution standards)? All we need to know is how much capacity is available, at what times, and at what prices.

Ultimately, that should be coordinated automatically, through a smart grid that matches demand with supply, at variable prices.

Roping in the private sector will open the energy mix up to a rival energy source which is less fashionable than renewable energy, but delivers reliable, dispatchable, efficient, and 100% clean and carbon-free electricity: nuclear power.

Coal-to-nuclear

The nuclear option has a major additional benefit, which is that coal-fired power stations can be retrofitted with small modular nuclear reactors, as drop-in replacements for coal-fired boilers.

Coal-to-nuclear conversions achieve the coal decommissioning that everyone ultimately wants, without sacrificing capacity, or the reliability and dispatchability that a stable grid requires, and without needing to build any additional grid connections. Existing buildings and steam turbines can be reused in this scenario, resulting in major construction cost savings.

Scientists agree that coal-fired power plants should get nuclear-ready. In the US, the government released a report that found hundreds of retiring coal-fired power stations can be converted to nuclear. The Electric Power Research Institute offers a practical guide for the deployment of a nuclear energy facility on or near an existing coal plant.

Imagine not having to uproot worker communities around end-of-life coal-fired power stations, but instead putting them to work in nuclear power plants on the same sites, so the only change in their life will be that they can breathe clean air, for a change.

Nuclear IPP

South Africa has a deep history of nuclear research and expertise, and a local consortium, led by venture capitalist André Pienaar’s firm, C5 Capital, is moving ahead with a plan to construct a series of small modular reactors in the Western Cape, as part of Eskom’s independent power producer (IPP) programme.

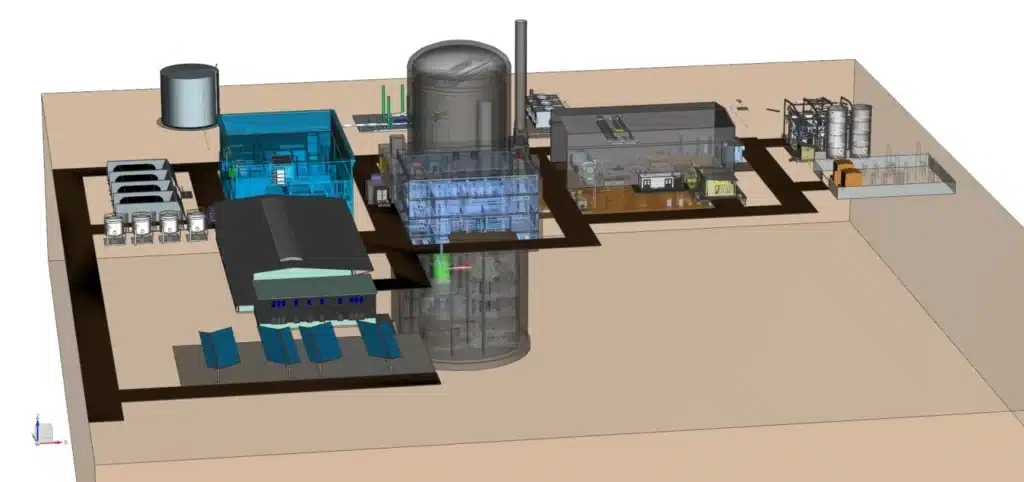

It proposes to use the HTMR-100 design (pictured below) from Stratek Global, a South African nuclear firm. It is based on 25 years of research, primarily associated with the pebble-bed modular reactor programme that the Zuma government abruptly abandoned in 2010 in favour of a corrupt deal with the Russians.

Alec Hogg, editor of BizNews, conducted an half-hour interview with Stratek Global’s chairman, Kelvin Kemm, who tells a fascinating story of the history of nuclear energy in South Africa, and its prospects for the future.

All of the above

The future of South Africa’s energy landscape must be an ‘all of the above’ approach. It cannot prematurely abandon coal. In fact, it should refurbish failing coal-fired power stations to improve their performance.

South Africa needs to urgently stop burning money in diesel-fuelled gas turbines and replace that with reliable additional capacity. Some of that will be renewable, certainly, but renewable energy is no panacea.

The future isn’t green. It is greener. Nuclear power is as clean and safe as solar or wind, but also solves all of the drawbacks of renewable energy: intermittency, variability, and the need for a multitude of grid connections. It can even be used to upgrade retiring coal-fired power stations.

And it’s home-grown technology, to boot. What’s not to like?

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend

Image: A wind turbine in front of two nuclear power cooling towers, which produce only steam, in France. Unknown photographer; attribution not required under Creative Commons CC0 licence.