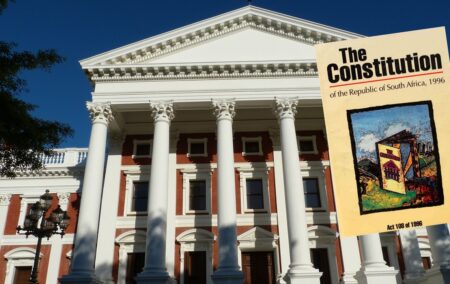

As the country teeters on the brink of disaster, it would be prudent for South Africa to think carefully before tinkering with constitutional amendments on property rights.

Rightly enough, the weight of public interest about the course on which the African National Congress and the government seem intent on setting the country has been on the impact it will have on South Africa’s foundering economy – specifically whether this is something that will drive or forestall an economic recovery.

This is particularly the case now that the report of the presidential advisory panel on land reform and agriculture has been published, coming out in favour of granting some fairly extensive powers to the state to take assets and to cut into private property rights. It is a matter of debate (and concern) what this will mean to property markets, the farming economy and the investment environment.

Less widely canvassed has been the impact on the country’s governance order. A number of news outlets have contented themselves with the panel’s apparent endorsement of property rights, and have had relatively little to say about its endorsement of constitutional amendments. Perhaps the latter is considered a lost cause, with Parliament’s Constitutional Review Committee having decided on the matter.

Besides, some comfort might have been drawn from the notion that the amendment might be clarificatory in nature, to ‘make explicit that which is implicit’.

Indeed, some voices have been rather more positive about the report. Daily Maverick columnist Professor Balthasar writes that the panel’s report provides a means to stave off a looming constitutional crisis. Such a crisis, he writes, is arising because of governance and political dysfunction, alongside (and related to) an economy which is failing to deliver inclusive growth.

The report, his piece argues, recognises the key issues that need to be addressed and sets out recommendations that would (presumably) do so. Hence: ‘A good start would be a deliberate and meaningful commitment to the implementation of the panel’s recommendations, which may well tilt the balance in favour of the constitutionalists in this country as opposed to the populists and their opportunistic discourse.’

This echoes to an extent what Professor Steven Friedman wrote last year about the prospect of a constitutional amendment. In his view, it could produce ‘better’ property rights in that it might increase the level of certainty around them, which would in turn make it possible for property-holders to plan to keep their assets safe.

These arguments foreground – again, rightly enough – that poverty, economic exclusion and so on pose very real threats to constitutional governance and property rights.

Whether the courses of action they propose are correct antidotes is rather less clear. The threat to the country does not arise solely from the dreadful economic realities that beset so many millions in South Africa. Its roots are also firmly implanted in an ideological worldview that has long been dirigiste and party-centred.

This has done no small amount of damage to the country and to its economic prospects. The imperatives of party control and party ‘unity’ have seen an unlawful and wholly reckless programme of cadre deployment play havoc on the state system and prioritise the sensitivities of teacher unions over the interests of their wards’ education, and have seen the state refuse to give title to land made available to beneficiaries of its redistribution programme.

As a general principle, property ownership, in this view, is viewed at best ambiguously. It is a sort of privilege extended by the state, and which needs to be reined in.

Amending the constitution will prove a very poor response. The Bill of Rights sets out some fundamental protections; it has never been tampered with before. And the prompt for this action is not that any evidence exists that it is undermining land reform. Even President Cyril Ramaphosa – and he is not alone, here – has made the argument that the constitution in its existing form would permit expropriation without compensation. No, this is about long-standing ideology, party resolutions and grubby politics. It scapegoats the constitution and mangles it to make a political point.

Seen from this angle, whatever its motivations, the panel’s recommendations to proceed with constitutional amendments will likely undermine constitutional governance.

And this is a precedent that could be rolled out elsewhere. Prescient observers might recall attacks on the media since the 1990s – accusing it of being unpatriotic, unconstructive, and so on – something that might quite conceivably become the basis for diluting free expression. Particularly given the concerns that Prof Balthasar has voiced about the strong presence in positions of influence of people and interests quite prepared (even eager) to dispense with constitutionalism.

Moreover, the persistence of the economic malaise and the inability of the country’s poor to gain an economic foothold and reasonable prospects for mobility do indeed pose a danger to the country’s future. Redistributive measures have an important role in addressing such problems, but these will be of little long-term value if they are not paired with the economic growth that will drive both the creation of wealth and the generation of employment and entrepreneurial opportunities that the country so sorely lacks.

Measures that seek to expand the role and discretion of the state – the state as it exists, not an imaginary entity that has been cleaned up in the future – to limit in effect people’s hold over their property, stands to do precisely the opposite. It already has inflicted damage and is a red flag to investment, inimical to a growth-oriented future. The result could well be a body blow to South Africa’s constitutional democracy.

As the country teeters on the brink of disaster – a sentiment no longer confined to ashes-and-sackcloth prophets in lonely places, but shared by senior politicians and civil servants – it would be prudent to think very carefully about the full range of implications of embarking on this course.

Terence Corrigan is a project manager at the Institute of Race Relations.

If you like what you have just read, become a Friend of the IRR if you aren’t already one by SMSing your name to 32823 or clicking here. Each SMS costs R1.’ Terms & Conditions Apply.