Walking is always the best way to get to know foreign places, at the human scale that walking the streets always promises. But the same is just as true of neighbourhood settings which we might assume are so familiar that there is nothing new to discover in them.

I learned as much when my car went in for extended repairs recently and there was nothing for it but to walk to the shops for bread and milk. I noticed things I’d never spotted from the car.

Two sightings established themselves in my ambulatory consciousness as being somehow, more or less obviously, connected. The first was a crudely but efficiently assembled bundle – bedding, undoubtedly, of a kind anyway, perhaps some clothes, and, though unseen, possibly some rudimentary utensils for preparing a meal – which had been jammed into the fork formed by two of the umpteen thigh-thick limbs of a huge Morton Bay fig just a few metres from the freeway near my home.

You had to be a walker, and a fairly attentive and curious one, to spot this evidence of human ingenuity, or desperation. The vast tree curtains the view from the roadway; I doubt any passing motorist has ever seen that bundle. Also, the fig’s shadows obscure the tell-tale blackening of the lower bough that gives away the site of the absent itinerant’s fireplace.

Perhaps poverty and homelessness are so unremarkable as to make signs of ad hoc habitation seem an ordinary feature of the fragments of road reserve or open ground in the suburbs where a big tree or a hedge lends itself to temporary or surreptitious shelter. Even when spotted fleetingly from our cars, they probably barely register. Walking by, however, there’s time enough to observe and imagine; you wonder what it would be like, and how you would manage.

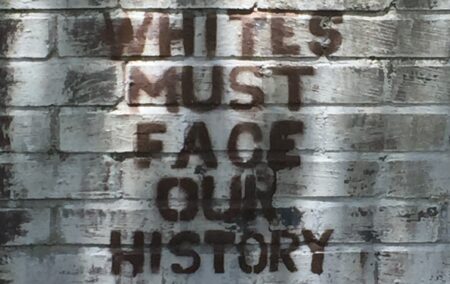

Which is why the next thing I noticed caused a jolting association. It is, in fact, the image that illustrates this article. Neatly rendered, as graffiti goes, the stencil-style statement on a small brick structure not far from the tree is part admonition, part remonstration, part plea: ‘Whites must face our history’.

Even as I took the photograph with my cellphone, I was thinking about that stout bundle lodged out of sight in the fig tree. And I was thinking about what was right and what was wrong about reading these two things together.

It is, in fact, what is right and what is wrong about the core argument in South Africa today.

That the statement seems apt in this particular setting is deceiving, for the seeming appropriateness embodies the falsity of a subject and helpless majority suffering at the hands of an acquisitive, uncaring minority.

On the surface, but only on the surface, it looks right.

Mine is a white neighbourhood. That’s not completely true, but I can count on the fingers of one hand the residents I am aware of who are not white-skinned. And, in contrast to the portable ‘home’ hidden in the fork of that Morton Bay fig tree, homes in this neighbourhood change hands for millions of rands.

Implicitly, something is amiss, for we all know that that bundle in the tree represents not the solitary exigencies of a lone urban nomad, but the plight of a mass of poor, deprived people who number in the millions. And the houses that change hands at seven-figure sums represent, broadly, a minority whose accomplishments and endowments are not separable from a history of advantage, and the privilege of circumstances in which their doubtless considerable efforts and talents qualified them for compounding rewards.

Thus, between the bundled bedding and the slogan, we are told, lies the chasm of want, indifference, irreconcilability and social failure – history’s indictment of the present.

You can put hard numbers to it.

A crisp outline is provided by the Quality of Life Index developed by the Centre for Risk Analysis (CRA) at the IRR in 2017 to benchmark progress in improving South Africans’ quality of life against ten key indicators (measured on a score of 0 to 10).

These indicators are the National Senior Certificate (NSC)/matric pass rate; unemployment (based on the expanded definition); monthly expenditure levels of R10 000 or more; household tenure status (houses owned but not yet paid off to a bank); household access to piped water; access to electricity for cooking; access to a basic sanitation facility; irregular or no waste removal; medical aid coverage; and the murder rate.

The CRA has just published its latest Quality of Life Index, which describes a society whose policies are continuing to make a pitifully inadequate impact on the material conditions of most people.

The latest Index finds that white South Africans have the highest standard of living, with a final score of 8.1 (excluding the murder rate) or, including the murder rate, 7.9 – both far above the national average of 5.7. Indicators in which white people have the best outcomes are the matric pass rate, unemployment, expenditure exceeding R10 000 per month, mortgaged houses, waste removal, medical aid coverage and access to a basic sanitation facility. Outcomes for black people are worst on all indicators, with an overall score of 5.4.

We also know that the economy has performed abysmally, with a growth rate of under 1% for the year, unemployment has steadily risen to 29% (nearly 7 million people by the official definition, or 10 million by the expanded definition), and more than 10 million people rely on 17 million monthly social grants.

Three things are inescapable. Expanding, not reducing, the tax-paying middle class is critical to restoring South Africa’s economic dynamism and also maintaining the social safety net that keeps the millions of grant recipients from destitution.

The second is that ‘our history’ now incorporates a full quarter of a century of democratic rule. For all its initial successes in overcoming the very considerable burden of the apartheid legacy, democratic rule has resulted in failures in education and empowerment, and a failure to stimulate job-creating investment. These have to be factored into the explanation of the distance between that bundle in the tree and the comfortably off household nearby.

The third is that what is patently obvious is that imploring – or insisting or somehow compelling – ‘whites’ to ‘face our history’ at once misperceives the problem and offers nil by way of a solution.

Commentator R W Johnson wrote just last week that the ANC and the government ‘are extremely uncomfortable with any suggestion that twenty-five years in power means that they must be responsible for what has happened’.

Unarguably, however, the primary agency in South Africa today – which, in a genuine sense, is something to be celebrated – is its democratically elected government.

But if that government fails to confront our history, recognise its own failures, and summon the courage and political wisdom to correct them, the millions represented by the bundle in the fig tree will have little to hope for.

That really is the writing on the wall.

If you like what you have just read, become a Friend of the IRR if you aren’t already one by SMSing your name to 32823 or clicking here. Each SMS costs R1.’ Terms & Conditions Apply.