This Week in History recalls memorable and decisive events and personalities of the past.

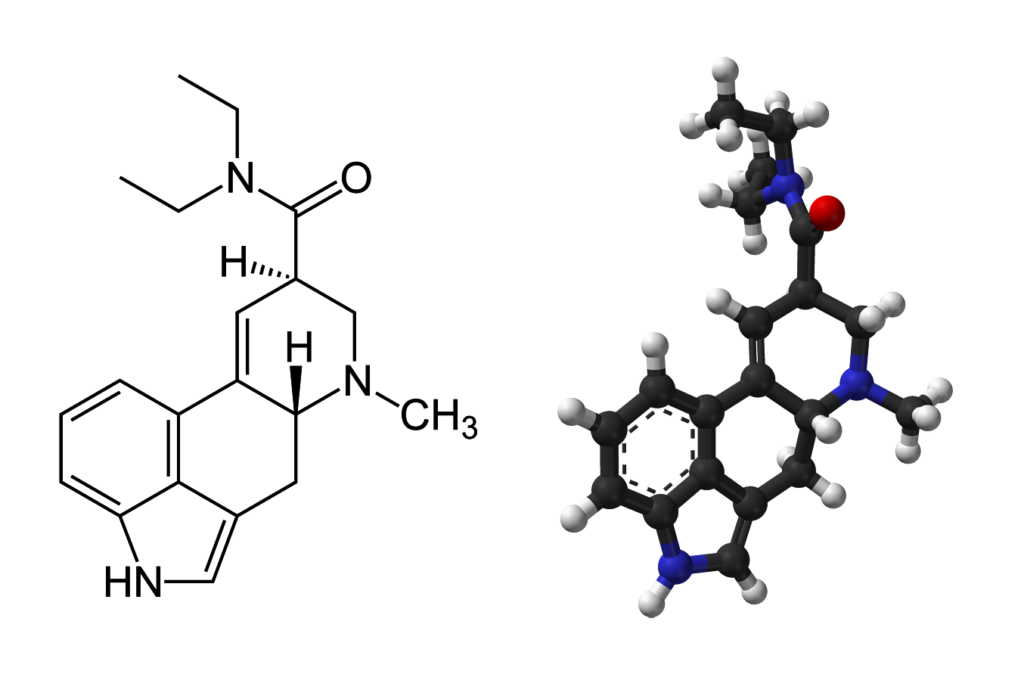

16th November 1938 – LSD is first synthesized by Albert Hofmann from ergotamine at the Sandoz Laboratories in Basel

Lysergic acid diethylamide, or LSD as it is more often called, is a drug which has had a major impact on global culture and society.

It was first created in a lab by Swiss scientist Albert Hofmann in 1938.

Hofmann was working for a pharmaceutical company at the time, attempting to create new medications from various natural ingredients. In this instance, he was attempting to create a respiratory and circulatory stimulant. After synthesising the drug, he decided it wasn’t important and set it aside for a few years. In 1943, he decided to resynthesise the drug, and in the process absorbed a small amount through his fingers.

He described the effects thus:

‘[I became] affected by a remarkable restlessness, combined with a slight dizziness. At home I lay down and sank into a not unpleasant intoxicated[-]like condition, characterized by an extremely stimulated imagination. In a dreamlike state, with eyes closed (I found the daylight to be unpleasantly glaring), I perceived an uninterrupted stream of fantastic pictures, extraordinary shapes with intense, kaleidoscopic play of colors. After some two hours this condition faded away.’

A few days later he ingested 250 micrograms intentionally to further experiment with its effects. This was the world’s first intentional LSD trip. Hofmann continued to take the drug in small amounts for the rest of his life, believing it to be helpful with meditation and spiritual development. He also hoped to find a medical use for it but was ultimately unable to. In 1971, the United Nations declared LSD a Schedule 1 controlled substance and the drug has remained illegal almost everywhere since.

The drug had a major influence on the counter-culture movement of the 1960s and it was commonly associated with Hippie culture and lifestyles in the United States.

18th November 1095 – The Council of Clermont begins: called by Pope Urban II, it led to the First Crusade to the Holy Land

The story of the First Crusade begins not in the halls of the Roman Catholic Church but in the east, in the Imperial palaces of the Eastern Roman Empire in Constantinople. The Eastern Romans had since the mid-9th century been on a path of recovery and were expanding back into territory that the empire lost control of during the Islamic and Slavic invasions of the 7th to 8th centuries.

At the start of the 11th century, the Byzantines had defeated the Bulgarians and reincorporated Bulgaria into the empire. They were also pushing the last remnants of the now fractured Islamic Empire back across Asia Minor and now took control of many of the valleys and hills of Armenia. Unfortunately for the Byzantines, a new enemy had arrived in the Islamic world to their east. The Seljuk Turks had conquered much of Persia, Iraq and were now present in Syria. Turkic tribesmen, many of whom were not affiliated with the Seljuk sultan, were migrating towards the grasslands of the Anatolian plateau and this threatened Roman control of their eastern border.

While a showdown between Romans and Turks was developing on the Eastern frontier, in the west trouble was brewing too (covered in this edition of This Week in History).

The Bishop of Rome, today more commonly referred to as the Pope, was seeking to grow his influence over all the Christian church. While the Bishop of Rome had long been held as one of the most important churchmen in the Christian world, the true extent of his power was not agreed upon by all. Indeed, the Eastern churches based in Alexandria, Constantinople, Jerusalem and Antioch were far less accepting of Roman superiority. The Patriarch of Constantinople (the head of the church in that city and the Eastern Roman empire), in particular, was discomforted by Rome’s claims to supremacy over the church. Other concerns deepened the division between the Eastern and Western Churches; there were minor theological differences, and a falling out when Charlemagne was declared emperor of the West by the Pope in 800.

These tensions culminated in a breakdown of the relationship between the Patriarch of Constantinople and the Pope in 1054. The Pope had put out feelers through the Patriarch to the Eastern empire to try and mend the growing rift and form an alliance against the newly arrived Norman invaders in in Italy. These negotiations broke down and due in part to poor Eastern Roman management of a visiting papal cardinal, the cardinal used his authority on behalf of the Pope to excommunicate the Patriarch of Constantinople, who in turn excommunicated the Cardinal.

The Pope on whose behalf this had been done died soon after and the issue remained resolved. This event would come to be known as the ‘Great Schism’ and is often seen as the point at which Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches formally split. (In reality the story is much more complicated, but that is a tale for another time).

A few years later on the eastern frontier, the Romans suffered a massive defeat at the hands of the Turks at Manzikert in 1071 and then faced an invasion from the Normans.

This brought the empire to the verge of collapse and the Emperor Alexios reached out to the Pope for help against the Turks.

The Pope, seeing a chance to reunite the Eastern and Western Churches, turn the violent and destructive energies of Europe’s knights outward and finally get the East to accept his claims to superiority, sought to encourage nobles across Europe to march to the defence of the Eastern Church.

On 18 November 1095, Pope Urban II convened a church council attended by nobles and clergy in what is today Clermont in southern France at Clermont.

On 28 November, the Pope gave a speech at this council. While we have some accounts of this speech, these were written much later and differ from one another, so we don’t know precisely what was said. The sentiment of the speech was that the church was under threat by the Muslim armies of the west and it was time for the Knights of Christendom to take up arms and defend the East against the infidel.

To everyone’s surprise, the call was answered by an enormous number of both commoners and knights across the Christian world, who, in ragtag groups, would march off towards the Eastern Roman empire to fight the Turks and see the Holy Land. The First Crusade had begun.

The Eastern Romans had hoped for a single organized army to aid them, not the chaotic mess of many small groups which arrived suddenly on their doorstep.

The Emperor Alexios would have to do a lot of managing and diplomatic balancing to marshal the crusade, but that is a tale for another time.

19th November 1944 – Second World War: Thirty members of the Luxembourgish resistance defend the town of Vianden against a larger Waffen-SS attack in the Battle of Vianden

The tiny country of Luxembourg tends to go unnoticed in world affairs. Formed in the aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars, it was originally held in a personal union by the king of the Dutch but became independent in the 1890s. The country of Luxembourg was seen by both France and Germany, its two large neighbours, as a buffer state and both promised to respect its neutrality.

This was violated in 1914 when the Germans invaded the country as part of their efforts to invade France at the outbreak of the First World War. Despite the invasion, Luxembourg was allowed to keep much of its independence and stayed out of the war for the most part.

When the Second World War broke out in 1939, Luxembourg once again sought to stay neutral, but was invaded by the Nazis in 1940, and due to its tiny size was unable to resist. Unlike in the First World War, the Germans this time treated the country as though it was part of Germany and informally annexed it into a neighbouring German province. The Luxembourgish government had fled to London and encouraged resistance to the German invasion.

In 1941, the first resistance groups, such as the Letzeburger Ro’de Lé’w, were formed and began to undermine and combat the German occupation. In 1941, the Germans attempted to conduct a census in the country to formalise their annexation. The Nazis wanted the locals to answer that they were Germans on the census so that Germany could annex the territory, claiming it was entirely German. The resistance campaigned in secret against this plan and early polls showed that the Nazi strategy appeared as if it would fail, as majorities of the respondents described themselves not as Germans, but as Luxembourgish.

Resistance continued throughout the war and, in September 1944, the country was finally liberated by British and American troops who were pushing the Germans back towards Berlin. Members of the resistance were armed by the allies and formed into a militia who took up positions along the German border and at observation posts.

One of these posts was the Castle of Vianden, which gave the Luxembourg troops an excellent view into Germany and allowed them to supply info to the American artillery and air force to attack German targets.

After a clash between Luxembourg resistance fighters and German troops on 15 November 1944, the Germans decided to capture the castle. On the morning of Sunday 19 November, 250 troops from the German Waffen SS attacked the castle and its small garrison of 30 Luxembourg soldiers.

Heavy fighting ensued. Six Germans broke into the castle at one point and were engaged in hand-to-hand fighting with the defenders but were pushed out. After several failed assaults on the castle and the nearby village, the Germans were forced to retreat, having suffered 23 dead. The Luxembourg defenders suffered only one dead and six wounded.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend