This Week in History recalls memorable and decisive events and personalities of the past.

29th April 1091 – Battle of Levounion: The Pechenegs are defeated by Byzantine Emperor Alexios I Komnenos

The many nomadic and semi-nomadic peoples of the Steppe have had a great impact on all the history of Eurasia and yet we still know relatively little about them, especially from their own perspective, as the people who inhabit the great grasslands stretching from Hungary to China did not have much of a literary culture for most of history.

Nevertheless, we do know something about these people from accounts mostly written by their enemies and neighbours in the settled world, and thankfully both the Chinese and the Greeks especially have provided us with fascinating records of the lives of the steppe peoples.

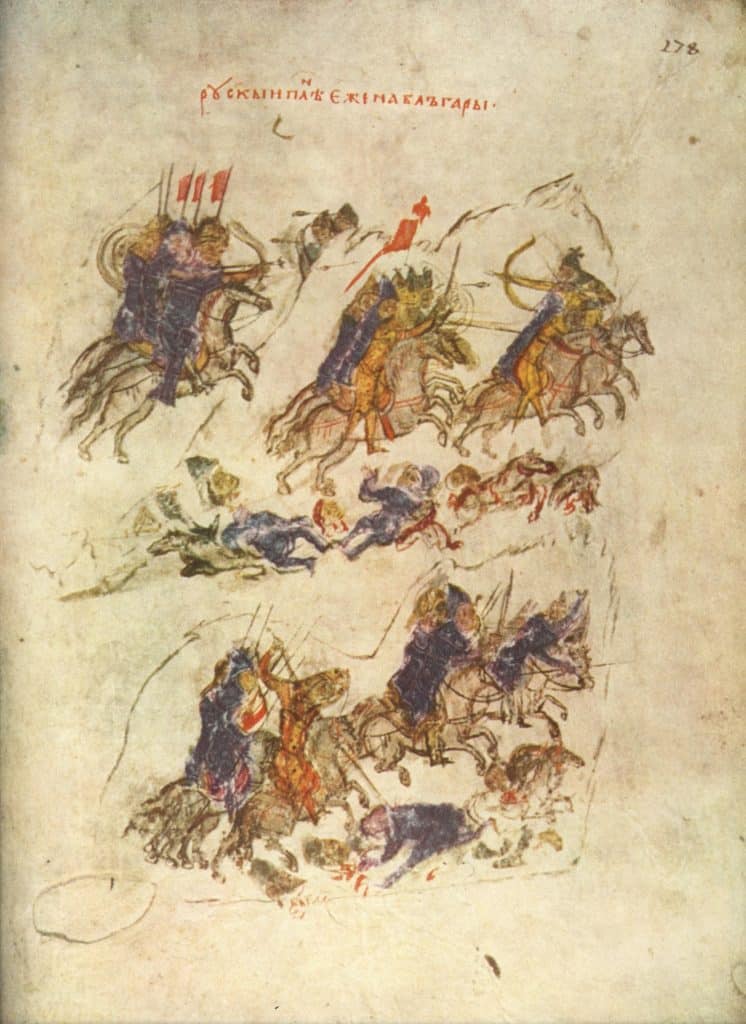

One of these groups are a western Turkish people, known to English-speaking history as the Pechenegs.

This group of horse-riding nomads came to be well known by the settled peoples in the 9th century and controlled an area that straddles what is today southern Ukraine and eastern Romania. The Pechenegs famously entered history as the people who drove their enemies, the Magyars (Hungarians), westward off the Steppe to settle on the Carpathian plain. (You can read more about the early Hungarians in this edition of This Week in History.)

The Pechenegs likely originated from the area of Central Asia, west of the Aral Sea and were pushed westward by conflict with other nomadic groups. They became the major power in the 9th century, replacing the Khazar Khanate which previously controlled the area.

In the ancient and medieval world, steppe peoples made excellent warriors as their hard life of horse-riding, hunting and herding made them skilled horsemen and hardy warriors. Steppe warriors could ride, fight and disappear only to reappear at your weakest moment. They were also difficult to counterattack, since, if they faced a major attack by settled people, they could just flee into the endless grasslands and wait for their enemy to run low on supplies and then attack them.

Their only weaknesses were overcoming the barriers of walls, forests and the sea, where their lack of technology, and their horse-bound tactics, reduced their effectiveness. The steppe people were also often very politically divided and fought and raided each other as much as the settled peoples. In view of this, the powerful empires to their south (Persians, Romans and Chinese) would keep the tribes weak by bribing one steppe horde to attack the other.

The steppe peoples, and this was definitely true of the Pechenegs, often fought in the armies of settled peoples and were well paid, as they were highly sought after. When the Pechenegs first arrived on the shores of the Black Sea, they initially allied with the Eastern Roman Empire and were paid to help fight off the Romans’ main northern enemies, the Hungarians and the Rus.

However relations slowly soured and when the Romans suffered a serious defeat at the hands of the Seljuk Turks at the Battle of Manzikert in 1071, the Romans were thrown into chaos and without Roman troops available to defend the border, many of the Pechenegs looked across the Danube River with hungry eyes.

In 1087, 80 000 Pechenegs crossed into Roman territory looking for a place to settle and plundering as they went.

The Roman Emperor at the time was Alexios I Komnenos, who had come to the throne in 1081 and had spent his entire rule fighting an invasion by the Normans from Sicily and attempting to retake Anatolia from the Turks, who had captured it after Manzikert.

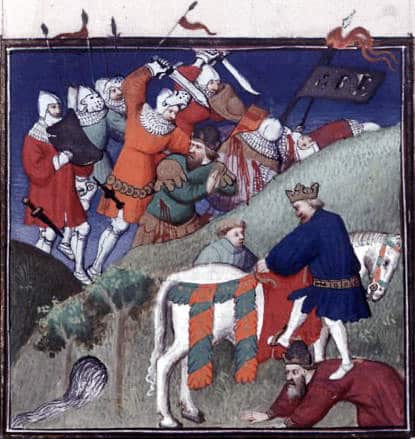

The Pechenegs initially were successful, but Alexios was a cunning commander and by 1091 had assembled a serious force of Roman troops, supported by Flemish, Frankish and Romanian mercenaries as well as steppe warriors from a tribe who were traditional enemies of the Pechenegs, the Cumans, whom Alexios had paid to fight alongside him.

With his army and allies from the Steppe, Alexios met the Pechenegs in battle at Levounion on 29 April 1091 (in European Turkey today). His army numbered 66 000 troops (26 000 Romans and 40 000 Cumans) against some 80 000 Pechenegs.

The Roman army managed to surprise the Pechenegs, almost the whole of whose force was massacred. As a result, the Pechenegs rapidly disappeared as an independent force. Their homeland north of the Danube was conquered by the Cumans in 1094, and over the next few centuries the remaining Pechenegs were gradually absorbed into the Cuman, Hungarian, Bulgarian and Roman populations.

There are few traces of the Pechenegs left today; some Hungarians have the surname Besenyö, which is the Hungarian word for the Pecheneg. And there is a small village in southern Serbia called Pečenjevce, which was founded by the Pecheneg survivors of the wars with Rome.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend