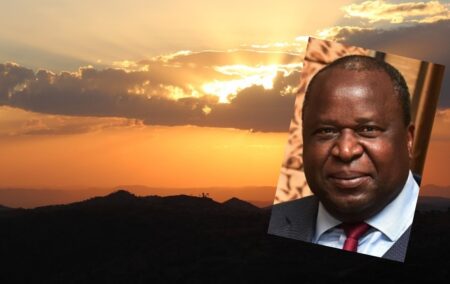

For all its flaws, finance minister Tito Mboweni’s document provides chinks of light in the gathering gloom, and the moderate majority should actively endorse it.

The SACP, Cosatu, and others on the Left seem incandescent with outrage over the strategy paper released last week by finance minister Tito Mboweni – but the moderate majority will find much to welcome in it.

On a quick scan, the document has many ideas that would help release the economy from its ideological straitjacket. Examples include:

Bringing down petrol, data, and electricity prices: This would be achieved by changing the petrol pricing formula, auctioning off spectrum (while keeping a small proportion under government control), selling Eskom’s coal-fired power stations to a range of purchasers, and allowing individuals and companies to sell their own (mostly) solar-generated power to a new state-run transmission grid.

Helping small business, by reforming labour laws (by removing the automatic extension of bargaining council agreements, for instance); adopting a Red Tape Impact Assessment Bill (to ensure the proper costing of future regulations and to cut existing red tape by 25% over five years); encouraging the government to pay its bills on time (by adding interest payments to outstanding balances after a certain period); reforming import tariffs (which may otherwise push up intermediate input costs for small manufacturers); and possibly lightening the BEE compliance burden (which weighs more heavily on small firms lacking the resources that bigger companies can deploy).

Improving transport logistics by encouraging competition and private sector participation in rail and port networks, and by allowing big cities and metros to take control of commuter trains and subsidised bus services.

Helping break the current housing logjam (the state needs another 20 years to resolve a backlog of 1.9 million homes) by facilitating the resale of social housing, fast-tracking the provision of title deeds to beneficiaries, and helping to unlock private-sector finance for low-income housing developments.

Promoting inclusive growth, by encouraging tourism (by revising damaging visa rules), expanding agriculture (through increased access to production capital, insurance, extension services, and markets); facilitating the immigration of skilled workers (to counter the skills ‘constraint’), and using special economic zones (to pilot further policy shifts before these are rolled out more widely).

The DA, the Official Opposition, which won 21% of the vote in the last election, has warmly welcomed the document as the basis for forging ‘a coalition’ that puts South Africa first. The SACP, which has never stood for election or won a single seat in Parliament, has stressed that it ‘will not allow’ this kind of ‘neo-liberal opportunism’ to proceed.

Cosatu, also an unelected ally of the ANC, has demanded the withdrawal of the document, saying it reflects ‘a right-wing agenda’ that was defeated in the past. The Southern African Clothing & Textile Workers’ Union (Sactwu), a Cosatu affiliate – which has presided over major job losses in the textile industry as labour costs have risen – is ‘alarmed’ at the document’s proposals. It describes its call for (limited) labour market reforms as ‘the most brutal attack on worker rights since the advent of democracy’. The EFF is outraged too, dismissing the document as ‘imperialism in action’. Equally angry is Neil Coleman of the Institute for Economic Justice, who accuses the Treasury of ‘having gone rogue’.

Where does President Cyril Ramaphosa stand? He seems to be balancing on the fence once more. When the document was released last week, ANC spokesman Pule Mabe praised it for its desire to ‘lessen public sector debt and boost business confidence’. But the Left’s angry reaction has prompted a retreat, and the president – far from strongly backing his finance minister – now stresses the need for ever more consultation so that an (unattainable) consensus can eventually be reached.

Why did Mr Mboweni release the document at this time? He may well hope that proposing some meaningful reforms while putting forward plans to cut state spending (supposedly by 5%, 6% and 7% over the next three years) will be enough to ward off a ratings downgrade by Moody’s.

However, the publication of the document also coincides with the release of a new study showing that the ratio of public debt to GDP – already set to reach 60% by the end of this financial year – will balloon to 100% by 2031 unless effective steps are taken to reduce state spending and stimulate growth.

But spending cannot easily be cut, while revenue collection this year is (again) below projections, emigration is rising (820 000 people reportedly left the country in 2017 alone), and the already high tax burden cannot realistically be increased. That leaves a faster growth rate as the best means of climbing out of the debt abyss. And growth cannot be attained without the reforms the document outlines.

As Business Day reports, the paper is not in fact new. Rather, it was drawn up by Treasury officials in 2017 to help flesh out the microeconomic reforms needed to catalyse faster growth. It was thus penned before the ANC’s Nasrec decisions to embark on expropriation without compensation (EWC), National Health Insurance (NHI), the nationalisation of the South African Reserve Bank (SARB), and the possible introduction of prescribed asset rules for pension funds and other financial institutions.

This helps explain why the document ignores these looming dangers (apart from the threat to the SARB, which it strongly rejects). There is also much in the document that is flawed. In particular, it is not nearly single-minded enough in its pursuit of economic growth, wanting to mix this with ‘transformation’ of the ‘radical’ kind. It also puts far too much faith in the capacity of the ‘developmental’ state and its ability to craft a winning industrial strategy.

The document is often inconsistent too. For example, it recognises the need to counter state monopolies in electricity, ports, and rail, but seems to share the ANC’s belief that breaking down big businesses is needed to help smaller ones succeed.

Mr Ramaphosa is likely to leave the document languishing in the consultation process for many months. But, for the first time in a long time, the reformist element within the ANC has shown clear signs of life. In addition, many of the document’s proposals are in line with the views of the moderate majority – which has little interest in grandiose redistribution, but desperately wants jobs and growth.

For all its faults and omissions, Mr Mboweni’s document provides chinks of light in the gathering gloom. The moderate majority should rally around it and actively endorse it. Without such support, the SACP and its allies on the Left, united in their fervour for a destructive national democratic revolution (NDR), will soon snuff out its glimmers of hope.

Dr Anthea Jeffery, Head of Policy Research at the IRR, is the author of People’s War: New Light on the Struggle for South Africa, now available in all good bookshops and as an e-book in abridged and updated form.

If you like what you have just read, become a Friend of the IRR if you aren’t already one by SMSing your name to 32823 or clicking here. Each SMS costs R1.’ Terms & Conditions Apply.