If, like the doomed United Party (UP), the Democratic Alliance (DA) fails to provide a clear alternative in voters’ minds, its electoral decline is inevitable.

The DA suffered an electoral reversal for the first time in its history on 8 May, with its national support dropping from 22.2% to 20.8%, and a loss of five seats in Parliament, its tally declining from 89 to 84.

In addition, its support dropped in six of the nine provinces, including in its Western Cape stronghold and the key battleground province of Gauteng.

Most of the lost support seems to have gone to the Freedom Front Plus (FF+), which saw its share of the vote more than double from just under a percent, to over two.

The reaction from the DA has been mixed, with two statements from the party contradicting each other. The DA’s federal executive, the party’s key decision-making body, said that the party accepted collective responsibility for the poor election result. Subsequently, party leader Mmusi Maimane said that he took ‘full responsibility’ for the dismal showing at the polls.

Some of the reaction has been somewhat surprising. In an interview with the Sunday Times, the party’s federal chairman (effectively Maimane’s No 2), Athol Trollip, suggested South African voters should do some ‘soul searching’. There were also reports that DA insiders were actually saying the loss was a good thing, as they had now jettisoned ‘racist’ voters who had decided to rather support the FF+. This narrative was repeated by DA officials and public representatives on social media.

Conversely, Maimane’s two predecessors as DA leader, Helen Zille and Tony Leon, both warned against painting former DA supporters who had abandoned the party for the FF+ as racist. Leon said on Twitter: ‘Blaming your own voters for leaving ensures they will never return.’

The DA, which seems unable to decide what kind of party it is, may be repeating the mistakes of two influential South African parties before it, neither of which exists any longer. Both the National Party (NP) and the UP tried to be all things to all people, leading to their electoral demise. Both also suffered from weak leadership towards the end of their existence, which (at first glance anyway) the DA also seems to be suffering from.

The UP was the governing party of South Africa until 1948, and was the political home of South African giants such as Jan Smuts and Jan Hofmeyr. After it lost power in 1948 to the NP, it also seemed to be torn between submitting to the race nationalism of the NP and agreeing that black people should have no rights in their own country, or whether to go leftwards and unambiguously state that South Africa had to become a democracy with voting and other rights for all.

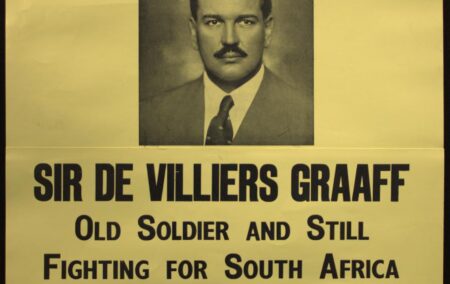

The party failed to challenge the NP at the polls in any significant way after 1953, and continued to lose votes on its left flank, initially to the Progressive Party, and in time to that party’s successors. After suffering its worst ever election result in 1974, winning less than a third of the vote and only 41 out of 171 parliamentary seats, the party disbanded. Its failure to offer (white) voters a compelling alternate vision for the country saw the party lose support at the polls as well as any hope of ever regaining power. And its leaders, in the shape of people like Koos Strauss and De Villiers Graaff, while well-meaning, did not have the gravitas or vision of men like Smuts or Hofmeyr.

A similar fate befell the NP, which had been the nemesis of the UP. The NP was a political colossus for most of the apartheid era, and, after the early 1950s, was never seriously threatened at the polls; it dominated South Africa’s politics until the early 1990s. However, by the late 1980s the combination of an economic downturn, the end of the Cold War, and rising domestic unrest, led to the inevitability of apartheid’s collapse.

It is needless to rehash the history of South Africa’s transition here, but in the country’s first inclusive election, the NP won over 20% of the vote, as well as control of the Western Cape. It co-governed with the African National Congress (ANC) in a government of national unity until 1996. And this, one could argue, is when the party’s problems began. The NP no longer knew if it was a party of government or opposition. It was also hampered by attempts to be attractive to its traditional Afrikaans constituency, as well as be a party for all South Africans. There were also ham-fisted efforts to rebrand itself, by putting the word ‘New’ in front of ‘National Party’. Leadership was also a challenge, with FW de Klerk being replaced by the ineffectual Marthinus van Schalkwyk in 1996.

The party’s failure to position itself as, well, anything, soon saw it lose support at the polls. In 1999, it won less than seven percent of the vote, and following a short and ill-fated marriage with the Democratic Party, it won less than two percent in 2004 (losing all its seats in provincial legislatures except in the Northern Cape and Western Cape).

In a sign that the universe does not lack a sense of humour, the (New) NP merged with the ANC in 2005, with Van Schalkwyk becoming a cabinet minister.

The DA now faces a similar predicament. What does the party stand for? Like the UP and NP before it, this is not particularly clear. For example, is it for or against policy based on race? Most people in the party would be hard-pressed to tell you. And it is not clear that Maimane has the steel of previous leaders such as Leon or Zille or, indeed, of someone like Julius Malema, to steer his party through what are sure to be some turbulent waters ahead.

The DA project is an important one. It is the only major political party which is unambiguously for free markets and trying to build the non-racial centre. The party seems to have lost sight of this goal, which has led to its present predicament. It must present a clear alternative to the ANC, instead of trying to copy it.

Like the NP and UP before it, a failure to provide an alternative, which is clear in the minds of voters, will see the party’s electoral decline continue. The party must be clear on what it stands for and what makes it different from the ANC. If it does not do this, the DA will repeat the fatal mistake, and join the UP and NP in the dustbin of South African political history.

Marius Roodt is the Head of Campaigns at the IRR.

If you like what you have just read, become a Friend of the IRR if you aren’t already one by SMSing your name to 32823 or clicking here. Each SMS costs R1.’ Terms & Conditions Apply.