This Week in History recalls memorable and decisive events and personalities of the past.

September 5th 1836 – Sam Houston is elected as the first president of the Republic of Texas

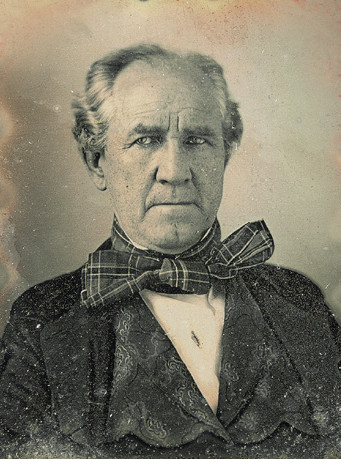

Portrait photograph of Sam Houston from a 1/6th plate daguerreotype

The US state of Texas is one of the country’s most iconic, with a reputation and an image that is instantly recognisable.

While Texas today has become a bit more like other states, it retains a distinctive identity and sense of self. To this day Texas has an unusually strong secession movement, with polling showing around 25% of Texans claim they support the state leaving the United States and becoming an independent country. If Texas were to become independent, it would have a population of 30 million and the 8th largest economy in the world.

The High Five Interchange in Dallas [austrini – https://www.flickr.com/photos/fatguyinalittlecoat/2909850055/, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=10298513]

This uniqueness can trace its roots back to the time when, before it joined the United States, Texas was an independent nation.

The region which came to be known as Texas has been inhabited by humans for thousands of years. Over the centuries it has been the home of many cultures and peoples whose names have been lost to history. There are some cultures which are known to modern historians, such as the ancient Pueblo people, whose descendants are still a recognisable group within the US today, and the “Mound Builders” of the Mississippian culture, a culture found across the southern United States which spanned the old world’s Bronze Age and the arrival of Europeans in the 16th century.

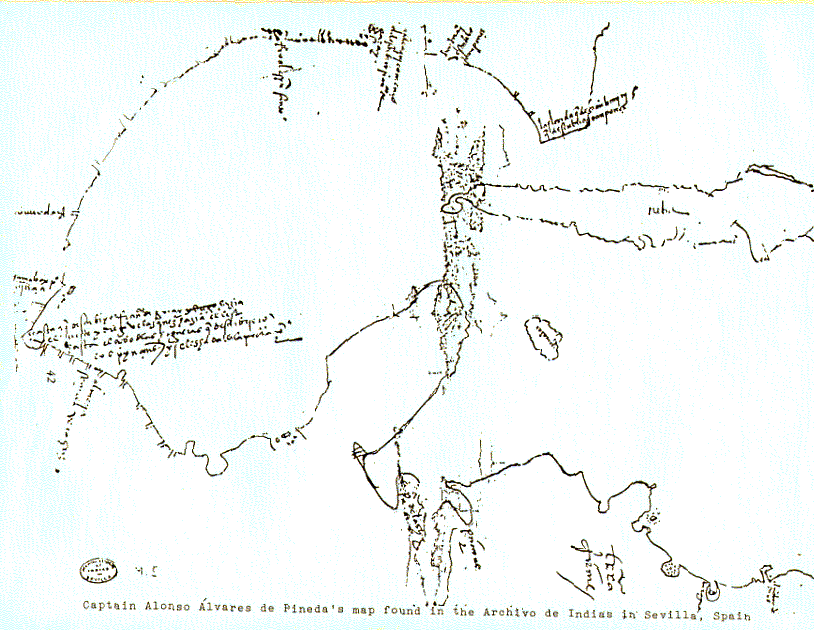

The first European to arrive in Texas was Spanish explorer Alonso Álvarez de Pineda, who mapped the coast of Texas in 1520, and claimed the region for Spain.

De Pineda’s map of the Gulf Coast

However, the territory remained on the fringes of European colonisation, with the relatively few contacts being limited to some trade between the local peoples and European traders.

The first Europeans to settle Texas were the French, in 1685. The French party had been attempting to settle along the Mississippi River but got lost and ended up in Texas, where they built Fort Saint Louis.

La Salle’s Expedition to Louisiana in 1684, painted in 1844 by Theodore Gudin. La Belle is on the left, Le Joly is in the middle, and L’Aimable is grounded in the distance, right

The fort didn’t last long, however; when a Spanish force arrived to evict the French in 1589, they found the fort in ruins, the local Karankawa people having attacked the settlement after the French had stolen some canoes. The Karankawa killed everyone except for four children.

In response to the French settlement attempt, the Spanish decided they needed to establish a colonial presence in Texas to prevent it being captured by another European power. In 1690 the Spanish established the Mission San Francisco de la Espada and in 1691 assigned a governor to the region.

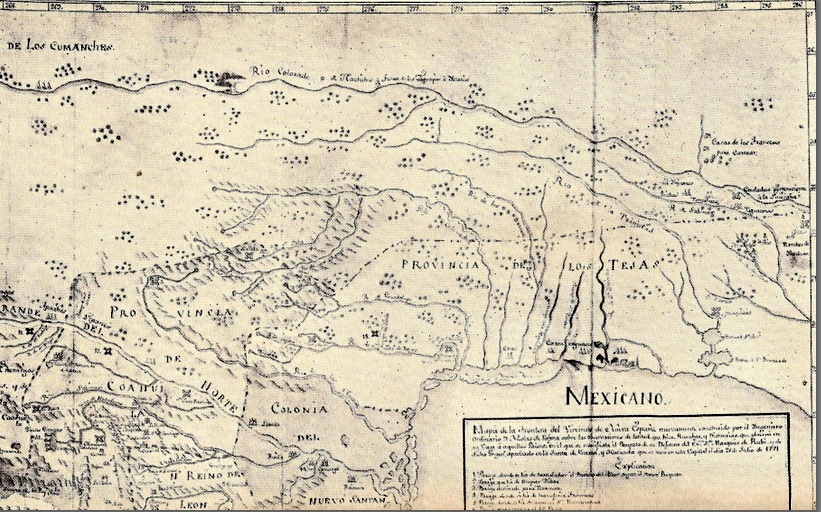

Nicolas de La Fora’s 1771 map of the northern frontier of New Spain clearly shows the Provincia de los Teja

Throughout the 1700s, Spanish settlement throughout Texas was fairly sparse, and focused mainly on missionary efforts to convert the local peoples to Christianity, which was largely successful. Settlement remained sparse, as much of Texas was under the control of the Comanche, who carried out near endless raids on European settlements and discouraged further settlement.

The Comanche were especially dangerous because during the 18th century they adopted horses and mastered mounted warfare.

War on the plains: Comanche (right) trying to lance an Osage warrior. Painting by George Catlin, 1834

Horses were introduced to the Americas by Europeans, and the Great Plains of the Central United States were the perfect environment for the nomadic Comanche and other tribes to become a horse-based culture. Adopting a lifestyle somewhat similar to that of Mongolic and Turkic nomads on the Eurasian steppe, the Comanche became deadly highly mobile warriors, who raided the Europeans and also drove out other tribes. The Apache had previously been the main group in much of Texas, but in the 1700s were driven out by the Comanche.

The birth of the United States would present a new threat to Spanish control of Texas.

In 1803 the United States purchased the claimed Louisiana French territory. This area was to the west of the United States and was poorly mapped, explored and defined, with some parts of Texas and the claimed Spanish territory in North America being claimed by the United States.

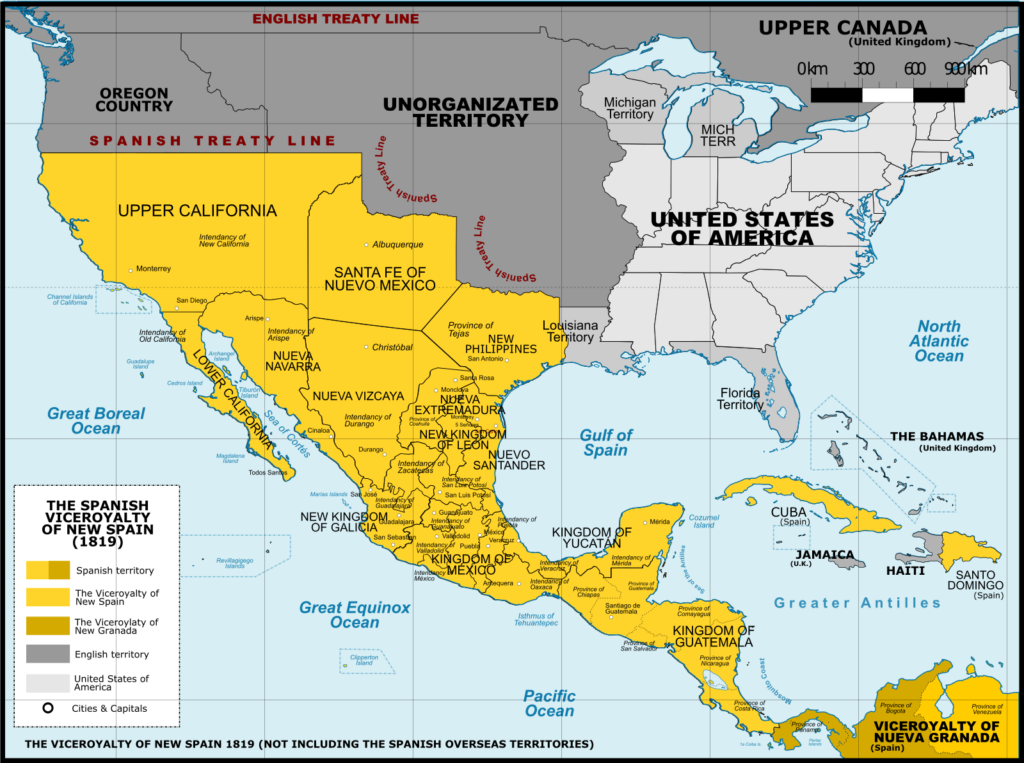

In 1819 the United States and Spain signed the Adams–Onís Treaty, which gave Florida to the United States in exchange for defining the border between the US and Spanish-controlled North America.

The Viceroyalty of New Spain in 1821, after the Adams–Onís Treaty took effect. (Note: Many boundaries outside of New Spain are shown incorrectly.) [Giggette, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=26601059]

This defined what would come to be the north-eastern and eastern borders of Texas, using primarily the Red and Sabine rivers.

In 1821, Mexico managed to secure independence from Spain and began encouraging European settlement of Texas in an effort to combat the Comanche. A key part of this policy was allowing American settlers from the United States, mostly Protestant English speakers, in contrast Catholic Spanish-speaking Mexicans, to settle in Texas.

In 1829, the Mexican government outlawed slavery. However, many American settlers in Texas had brought slaves with them when they settled there, and were reluctant to give them up. Initially an exemption was granted to Texas, but in 1830 the Mexican president ordered the end of slavery in all Mexican territory. The slave holders in Texas largely ignored this order and used loopholes to avoid freeing their slaves.

In 1830 the Mexicans became worried that they would lose control of the territory to America and now banned immigration into Texas from the United States. They also began imposing customs duties on goods flowing between the US and Texas, which angered Texans.

Mexico was plagued by political turmoil, and in 1832, during a revolt against the Mexican government in much of Mexico, the Texans revolted against customs enforcement. In August that year Texan militias defeated a government garrison and expelled Mexican troops from east Texas.

The Texans convened the Convention of 1832, which demanded more autonomy from Mexico, the formation of a new Texan state within Mexico and the end of immigration bans from the United States.

Stephen F. Austin was elected president of the convention

Some concessions were promised to the Texans by the Mexican government.

However, when Mexican president Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna’ in 1833 began to attempt to end the federal system in Mexico and centralise the country, outraged Texans revolted against Mexico.

In 1835 the Texan revolt began in full at the Battle of Gonzales. The Mexican government had loaned a cannon to the Texan settlers to fight off Comanche raids. As the political situation deteriorated the Mexican authorities decided to confiscate the cannon. This resulted in the Battle of Gonzales which the Texans won. In the aftermath, the Texans made a flag with a picture of a cannon and the words “Come and take it”, which has become a motto of Texan identity.

Detail of a mural in the museum at Gonzales, Texas

In early 1836 Santa Anna personally led a large force of Mexican troops into Texas to crush the rebellion, famously fighting a battle against a small group of Texans at the Alamo mission station.

The Fall of the Alamo (1903) by Robert Jenkins Onderdonk, depicts Davy Crockett wielding his rifle as a club against Mexican troops who have breached the walls of the mission

At the same time another Mexican force moved up the Texan coast, and infamously carried out a mass execution of Texan prisoners of war in the Goliad massacre.

“Remember the Alamo! Remember Goliad!” was to become the rallying cry of the Texan rebels, and remains part of Texan identity to this day.

As the Mexican army advanced, the Texan forces and their supporters fled. General Sam Houston was the main leader of the Texan army. In April 1836 his forces came upon intelligence that Santa Anna was close to the main Texan army, but with only a small force. The Texans attacked, winning the Battle of San Jacinto.

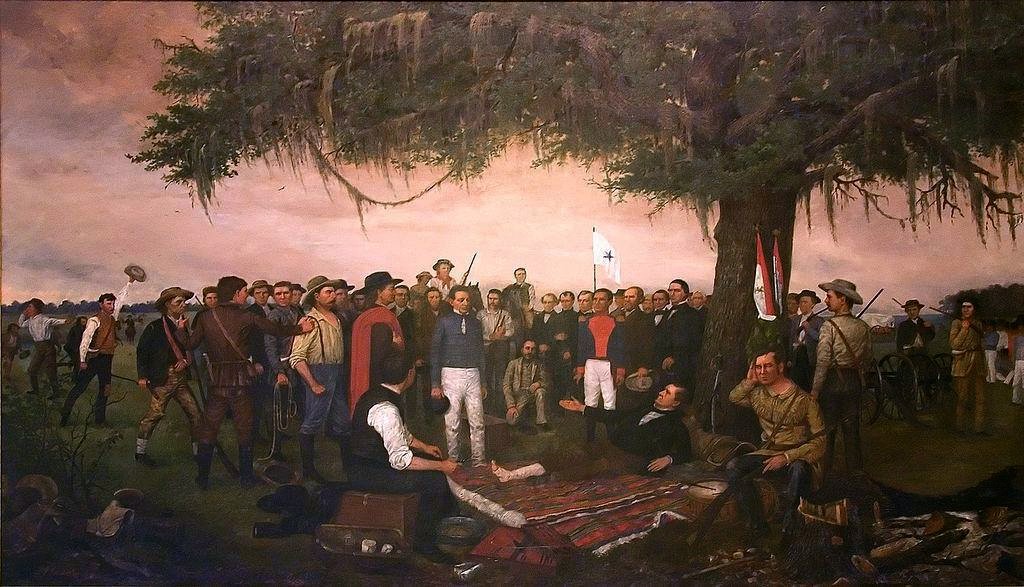

William Huddle’s 1886 depiction of the end of the Texas Revolution shows Mexican General Santa Anna surrendering to the wounded Sam Houston after the Battle of San Jacinto in 1836

Santa Anna fled the battle, but was captured by Texan forces the next day.

In captivity Santa Anna was forced to sign the Treaties of Velasco which granted Texas full independence from Mexico.

An outraged Mexican congress removed Santa Anna as president and rejected the treaties. Mexico refused to recognise Texan independence but was too weak to invade again and so Texas became the de-facto independent Republic of Texas.

On 5 September 1836 General Sam Houston was elected as the first president of the Republic of Texas.

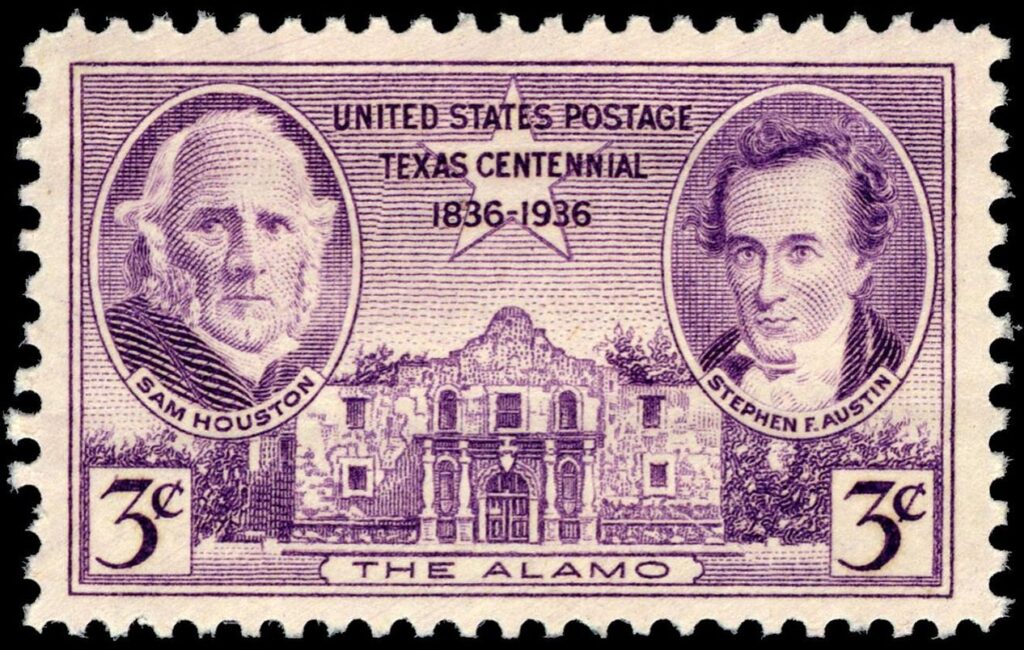

On March 2, 1936, the U.S. Post Office issued a commemorative stamp commemorating the 100th anniversary of the Texas Declaration of Independence, featuring Sam Houston (left), Stephen Austin and the Alamo

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend