A few days short of 30 years ago, South Africa turned back from the brink.

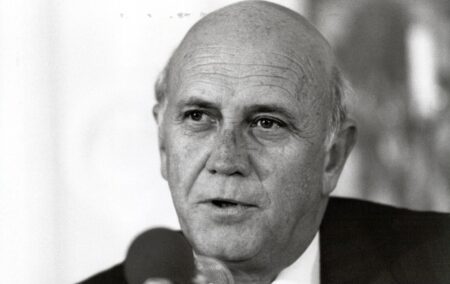

I remember it well. In the cool dawn of Friday February 2 1990, I was among the handful of political journalists walking up a nearly deserted Parliament Street for a 6am briefing at the presidential complex, Tuynhuys, on the Opening of Parliament speech due to be delivered five hours hence by the still relatively new incumbent, F W de Klerk.

As we crossed the cobbles, we speculated idly on the unlikelihood of anything earth-shattering in the speech, even if, in his four months in office, De Klerk had already demonstrated an unaccustomed boldness, and had begun to speak of change in a way that hinted at a fresh departure. ‘The trail of unmatched expectations over the years [of National Party rule] induced this rather guarded approach,’ I wrote in 1995.

In the briefing room, copies of the speech were duly handed out and, as we smoked and sipped our coffee, the intense silence was broken only by the rustle of turning pages. Then came the exclamations of disbelief as, umpteen pages into the text, we read the announcements which would soon reverberate around the country and the world, and set South Africa on a wholly new trajectory.

The unbanning of the liberation movements – which had operated underground and in exile since 1960 – dramatically widened the field of political competition, and created the essential condition for the long and difficult period of talks that ultimately produced a negotiated settlement, an interim constitution and the democratic election of 1994.

De Klerk later recalled that he hadn’t even told his wife all that he was going to say, though at the last minute he gave Marike a graphic indication of what it would mean; moments before delivering the speech as they stood on the steps of the great hall to take the national salute, De Klerk turned to her and said: ‘After today, South Africa will never again be the same.’

That was certainly true, and mostly in the best sense.

(One person who didn’t think so was Conservative Party leader Dr Andries Treurnicht, who fumed impotently that De Klerk’s address was ‘the most revolutionary speech I have ever listened to in this parliament’. It meant, he went on, that ‘the closet communists may come out into the open … we can be openly taunted with ANC-Communist T-shirts … they can shout in the streets: “Viva Comrade De Klerk!” I am shocked by this.’)

The emotion of the moment – euphoria but also justifiable optimism – intensified with the release of Nelson Mandela less than two weeks later. The new-look South Africa was borne on a wave of virtually unanimous goodwill.

Predictions at the time suggested – inconceivably – that South Africa could expect a constitutional settlement and a black government within a year or a year and a half at most. What followed, however, was four years of tough wheeling and dealing, and bloodletting on a scale far exceeding the violence of the entire 1980s.

When, finally, the deal was struck – the final version of the hard-fought interim constitution being approved by applause at the World Trade Centre in November 1993, and, not many months later, in April 1994, all South Africans voting together for the first time – De Klerk’s 1990 speech seemed a remote event, a turning point in a different country.

That, however, is what makes it so significant: it remains a symbol of possibility, of thinkable if hard-to-imagine departures.

When, 10 years later in 2000, I interviewed De Klerk on the anniversary of his speech – he was preparing to launch the F W De Klerk Foundation at the time, and recommit his energies to building on democratic South Africa’s successes – the former president began, with undisguised irritation, by rejecting what he felt then was a false nostalgia for a broken and unworkable ‘old’ South Africa.

Too often, he said, people ‘fall into the trap of comparing what concerns and worries them in the new South Africa with what they remember to be good things in the old South Africa’. But, he went on: ‘The true comparison … should be: what would South Africa have been like if I and the National Party had tried to cling to power, if I had not made that speech on February 2, 1990?’

As he had said before, De Klerk believed that ‘South Africa today, warts and all … is a much better place than it would have been’.

Even so, he was not without anxiety about ensuring ‘the tender plant of our young multi-party democracy gets stronger and does not wither in the heat of the present realities’, among them, crime, unemployment, corruption.

‘What we need,’ he added, ‘is a few quantum leaps … good policies coupled with good management. I believe in the future of South Africa, and I believe that if we do the right things, we can truly become a winning country.’

Good policies coupled with good management are not, by any stretch, an accurate description of what South Africans have been saddled with in the 20 years since. De Klerk’s confidence in the country that his own speech of 1990 did a great deal to realise has been affirmed – but for South Africa to become the winning country of his phrasing in 2000, we need another turn at the brink.

[Picture: Walter Rutishauser, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=70427110]

If you like what you have just read, become a Friend of the IRR if you aren’t already one by SMSing your name to 32823 or clicking here. Each SMS costs R1. Terms & Conditions Apply.