Living in South Africa, it is impossible to escape the raison d’être of Verwoerd and his ilk, decades after their death and 25 years into democracy. The recognition of individuals as representatives of racial groups determined not by shared values but pigmentation alone is the norm in our “rainbow” nation.

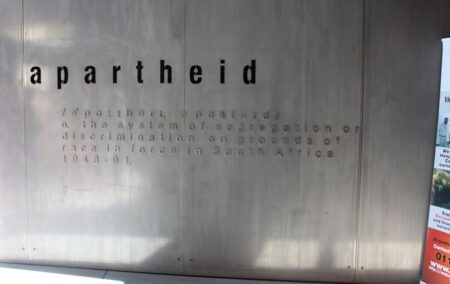

South Africa has a history of legislation that tainted the spirit of justice on these illogical and unsound premises.

Race as a form of social identity, outside of the practical function it plays in distinguishing types of individuals, is not real. Race as a social identity is a construct which, although it has guided social operations, rests on unsound grounds. These grounds seek to deny the individual nature of humans and subject each person to the external forces of the group. The sole criterion for describing a group is its pigmentation, a criterion that is not chosen – a shallow conception of identity if ever there was one.

Race is an act of comparison. Making it a social identity, though, is folly of the highest order, for there has never been any social identity worth its salt premised not on self-determination, but on reaction or comparison to an ‘other’, in which one’s analysis and actions are formed and judged by that comparison alone.

What distinguishes humans from animals is consciousness, will, soul; that which is within and which is given to no external being, outside of God. Identity stems from this; replacing it with race, a descriptor of biological processes at best, reduces individuals to mere biological processes, without agency.

The identity of the various peoples of Africa is not premised on pigmentation. African peoples did not consider themselves one group, based on their shared pigmentation; there is no evidence of this astounding claim. Indeed, there is evidence to the contrary, exemplified by the myriad of cultures dispersed across this wonderful continent and enchanting in their diversity. There is evidence both of commonalities and of vast differences in the cultures and ways of life across the continent, signifying a varied population who self-identify not as black people but as Isizwe sika Mageba, or otherwise as the Zulu nation, AmaMpondo, AmaNdebele, and so on. Race is not the premise of social identity.

The concept of group identity is not being interrogated here; what is being challenged is the absurdity of grounding it on the premise of race: a notion which fails to convince any sensible person.

Our history tells us that what made the previous regime abhorrent, and its conduct declared a crime against humanity, was its classification of individuals into racial groups and passing legislation and policy on the basis of racial groups. The previous regime was abhorrent because it considered racial group identity instead of individual identity not only as the primary but as the sole consideration when administering law and policy.

This is very similar if not exactly equivalent to what our present government is doing, fouling our constitutional order and era with some of the same logic and principles of its predecessors. Our government perpetuates an emphasis on racial groups instead of individuals when interacting with them; the government now targets other ‘colours’.

This absurdity is manifest in a myriad of ways, ways which we have seemingly normalised to our detriment. You will hear how many blacks sit on the board of this or that institution; how many blacks are in management in this or that sector; how many blacks are represented in this industry or that; how many blacks this, how many blacks that. The race of the individual has become our primary determination in evaluating individual conduct. This is so very sad.

Even though it may not always be expressly stated, the inherent logic of the state’s recognising racial difference perpetuates the false recognition of race as a social identity, ironically in the hopes of correcting the falsity itself.

Saying the state must not discriminate on racial grounds in the formal sense is not a denial of such discrimination by the state in the past. Quite the contrary, it is because we have seen and learnt the deplorable consequences of such discrimination by the state that we advocate for its absence! Beyond its consequences, we reject it because, on a principled basis, we recognise the unjust nature of such discrimination by the state. The government is not there to change the attitudes of its citizens, it is merely there to ensure peace as is envisioned by the Constitution and the Rule of Law.

South African civil society has relegated its duty of shaping and influencing the preferences and tastes of society to the state. By failing to act and claiming the space to do so, it has allowed the government to increase its power over the individual, determining everything, even the amount of sugar the citizen needs, as if that decision is the government’s to make! Racism and its effects should be handled by civil society; by abstaining from racial discrimination, the state’s role is fulfilled.

The state should ensure that restitution is not premised on racial grounds but rather on actual legal injury: if the two happen to coincide, then so be it. But, in meeting the constitutional duty of restoring the rights of people who were wronged, the basis should be not racial identity, but injury in law.

The concept of group injury that is assumed but never proven is simply ludicrous. It has been the rationale behind the most terrible of human atrocities, ours at home being an example among many globally and throughout time.

The problem of racism is not one to be dealt with by government in the positive sense. It requires a fundamental shift away from considering social identities through the lens of race, and that shift needs to be spearheaded by government – not through positive action, but by abstaining from using race as a social identity in dealing with its citizens and regarding them, instead, as the varied individuals that they are.

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR

If you like what you have just read, become a Friend of the IRR if you aren’t already one by SMSing your name to 32823 or clicking here. Each SMS costs R1. Terms & Conditions Apply.