This Week in History recalls memorable and decisive events and personalities of the past.

4th July 1187 – The Crusades: Battle of Hattin – Saladin defeats Guy of Lusignan, King of Jerusalem

In the late 11th century and early 12th century, the world of Europe and the Middle East was shaken by the crusades, a mass armed pilgrimage of Christians which had its origins in a call by the Pope to support the Eastern Roman Empire in the aftermath of serious setbacks at the hands of the Muslim Turks.

The Crusaders quickly fell out with their Roman allies and resolved to establish their own state in the ‘Holy Land’, which would serve to protect Christian pilgrims to Jerusalem and the holy places of Christianity, lost to the Islamic conquests of the 7th century.

The Crusaders were successful, in large part due to the power vacuum that existed in the Levant due to the clash of the Turkic and Egyptian empires, the two great Muslim powers of the time. The Crusaders established a number of ‘Crusader States’ namely the Principality of Antioch, the County of Tripoli, the County of Edessa, and the Kingdom of Jerusalem.

After the establishment of these states in 1099 and with their pilgrimage to Jerusalem complete, many of the Crusaders returned home to Europe, leaving a small force of knightly orders, such as the Templars, local Christians and adventuring European knights, to hold onto the kingdoms in a region surrounded by many hostile Muslim lords.

Over the next few decades through a combination of cunning diplomacy and stubborn resistance, the Crusader states managed to keep themselves intact often by allying some of their Muslim neighbours and participating in local conflicts.

By the 1140s, the County of Edessa found itself isolated after quarrelling with the other Crusader states, and after the death of an Eastern Roman Emperor who had been their ally. Seeking new allies, the Edessans established an allegiance with a local Islamic lord in Syria and were called to assist him in his fight against the Turkish lord of Mosul.

The subsequent battle saw the Crusaders routed, and the lord of Mosul soon captured most of Edessa, severely weakening the strength of the Crusader States. This and other setbacks for the Crusaders convinced Pope Eugene III to call for a Second Crusade which once again mobilised thousands of Christian knights and lords across Europe to travel to the Holy Land to support the Crusader States.

However the Second Crusade suffered from serious problems of coordination, which prevented it from achieving a coherent strategy. To make matters worse, the newly arrived Crusaders were full of religious fervor. Moreover, unlike the Crusaders who had remained in the Middle East and had adopted a pragmatic tolerant approach towards their Muslim neighbours and subjects, the newly arrived Crusaders saw no distinction between ally and enemy. This in part encouraged them to launch a disastrous attack on some of the Muslim allies of the Crusader States, resulting in their forces being defeated.

While the failure of the Second Crusade would put the Crusaders in a dangerous position, worse was yet to come.

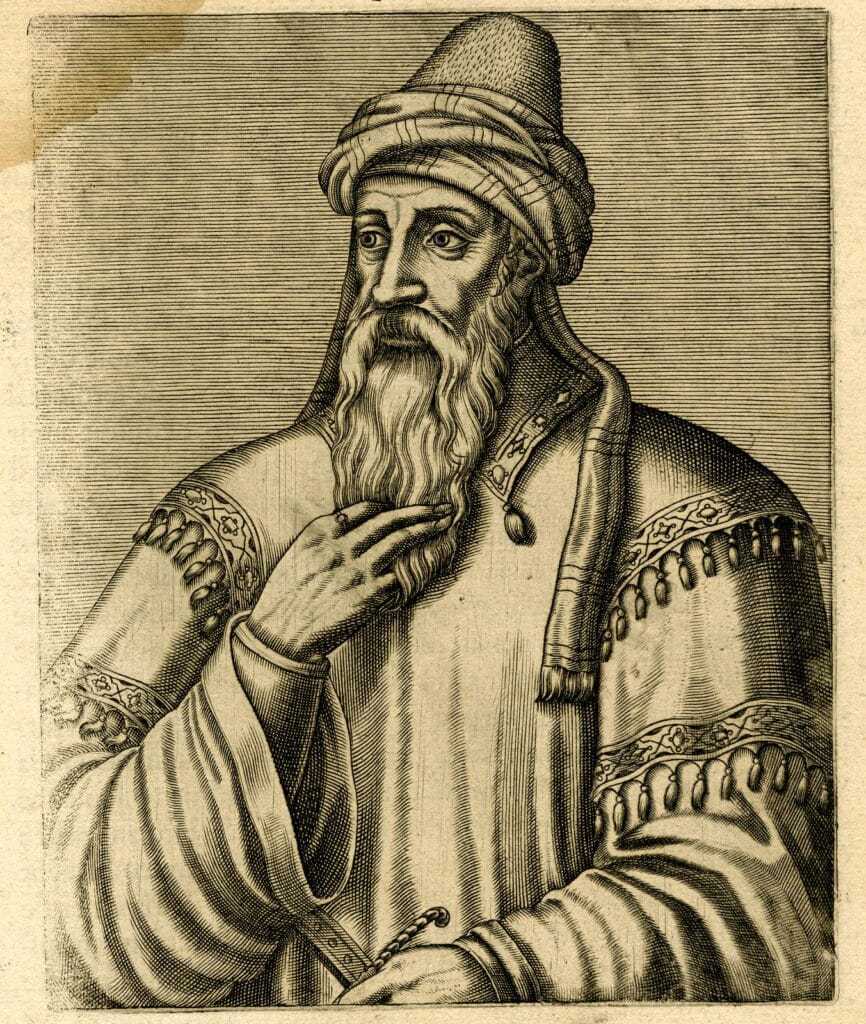

In 1164, a Kurdish Sunni Muslim, Salah al-Din (or Saladin), was sent by his lord in Syria to intervene in a dynastic dispute in the Shia Muslim Fatimid Caliphate, which ruled Egypt at the time. Saladin quickly rose through the ranks of the Fatimid military and defeated both Muslim and Christian enemies of the Fatimids.

After his appointment as Vizier (prime minister) of the Fatimids, he worked to undermine their control and in 1171 abolished the Fatimid Caliphate, appointing himself Sultan of Egypt, founding the Ayyubid dynasty.

With Saladin having consolidated power in Egypt, the Crusaders now faced a serious Muslim opponent on their southern border. Saladin moved quickly to secure more territory for his new kingdom; between 1174 and 1183 he captured most of Syria from rival Islamic powers. Now his kingdom almost entirely surrounded the Crusaders and there were no more local allies for the Crusaders to call on.

Skirmishes between Saladin and the Crusaders ensued. Saladin was rumoured to be planning an intervention in a succession dispute in the Kingdom of Jerusalem whereby he would place an ally of his on the throne and then establish peace. In 1185 Saladin signed a truce with the Crusaders, but a Christian lord, Raynald of Châtillon, who was newly arrived in the Holy Land, supported the candidate to the throne in opposition in Saladin’s choice.

Raynald was unhappy with the peace and so broke the truce in 1187 by attacking a Muslim caravan under Saladin’s protection. This reignited the conflict and the Crusaders suffered a number of military defeats at Saladin’s hands.

Saladin assembled a huge army and marched to lay siege to the Crusader-controlled city of Tiberias in modern-day northern Israel. Meanwhile infighting among the crusaders crippled their ability to make decisions and coordinate, and the King of Jerusalem, Guy of Lusignan, decided to march out with what remained of his troops and break the siege of Tiberias.

In the middle of a hot Middle Eastern summer, with poor supplies, the Crusader army marched north from Jerusalem. It was constantly harassed by Saladin’s troops. On the night of 3 July, as the Crusaders approached the city, they stopped to camp near an extinct volcano referred to as the Horns of Hattin.

Saladin’s troops positioned themselves between the Crusaders and nearby water sources, and then set fires in the dry grass. The lack of water, the smoke and the heat of the fires drove the Crusaders mad with thirst and they became extremely demoralised. This was made worse as Saladin’s troops beat drums, chanted and prayed loudly throughout the night, taunting the thirsty Crusaders.

The next morning the Crusaders attempted to break through the Muslim lines to reach the nearby lake. In a chaotic and desperate battle, some managed to break through to the water, but the majority, including King Guy, were surrounded and either fled or were captured by Saladin’s forces.

Most of the Templars, along with Raynald of Châtillon, were executed immediately, and the rest, including the king, were later ransomed back to their families.

Soon after, most of the Crusader fortresses fell to Saladin and he captured Jerusalem. This prompted the Third Crusade, which would see both the King of France and the King of England, Richard the Lionheart, take up the call to arms and lead armies to restore Jerusalem to the Crusaders.

6th July 1415 – Jan Hus is condemned by the assembly of the council in the Konstanz Cathedral as a heretic and sentenced to be burned at the stake

Growing up in a poor family in late medieval Bohemia (modern-day Czech Republic), Jan Hus sought to escape poverty by training as a priest. With a solid work ethic and great charisma, Hus quickly excelled in his studies as a priest and was soon ordained.

Hus went on to preach in Prague, and increasingly became critical of the Church establishment, denouncing some of its theological positions but also its wealth and the poor conduct of many of its priests. A fiery speaker, Hus drew large audiences and became more and more popular with the people of Bohemia, inspiring other priests to preach similar messages.

Concerned that he was undermining the church, the Bohemian church got the newly elected Pope, Alexander V, to excommunicate Hus from the church. This was initially not enforced due to his popularity in Bohemia, but eventually the authorities could no longer turn a blind eye to Hus, and forced him into exile.

Alphonse Mucha’sIn 1415, a Church council was convened in the city of Constance and Hus was invited to attend to make his arguments for reform, and with any luck settle the dispute between him and the Church.

Unfortunately for Hus, this was a trick; when he arrived in Constance, he was arrested and put on trial for heresy.

When the Church council demanded that he renounce his views or face death, Hus replied: ‘I would not for a chapel of gold retreat from the truth!.’

On 6 July 1415 Hus was burned at the stake for the crime of heresy.

This outraged his supporters in Bohemia who, now calling themselves Hussites, launched a rebellion against the Church. Between 1420 and 1431, the Hussite wars saw five crusades launched to try and stamp out the Hussites; all were defeated.

The Hussites are today regarded as proto-Protestants and brought up many of the themes of the later Protestant Reformation in their teachings. The example of Hus also caused reformer Martin Luther to reject a similar invitation to a church council more than 100 years later for fear that he too would meet the same fate as Hus.

One is left to ponder if the Reformation would have happened as it did had Hus not been executed in 1415.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend