My shirt is already wet with sweat when I get to the NG Church at Schweizer-Reneke on a Sunday morning in January 2019. I have spent days trying to understand why the town’s primary school has become the focus of such anger. Every major media house has condemned ‘that teacher’ for racism, but no one knew her name and it took me two days to find it. I enter the church with a mind full of questions.

One of Schweizer-Reneke’s mothers, whose testimony and photographic evidence vindicated Elsabie Olivier in rejecting the charge of racism, has told me she spoke up because she loved Olivier for the care she gave to her child. And also, she says, ‘God’s way is to tell the truth, even if the attackers come knocking.’

She is black. What will the predikant have to say to his congregation, I wonder?

People come in different sizes, different shapes, different colours, different ages, different levels of power and status and wealth, he explains, and yet ‘all are made in the image of God’.

This, the predikant tells his congregation, is a paradox. How can all things made in one image look so different? ‘Because God is love’.

The sermon of the day is an unambiguous celebration of non-racialism. Whatever the colour of your skin, he preaches, God looks into your heart and so we must look at one another.

Newcastle

It is the first Saturday of Spring in 2020 and I am driving through a boulevard of crosses with 3 000 others to mourn the murder of Glen and Vida Rafferty. There are 500 crosses on either side of the road, and more at the Raffertys’ old gate.

A Muslim family wave me down. ‘It is important that we stand united,’ the man says. ‘Our religion teaches that, we need to be united no matter what colour or creed you are’, adding that he hopes to ‘open the minds of government’ to the vulnerability of farmers and the need for proper respect.

Kranskop

I am looking at the graves of ancestors, the resting place of amadlozi, to solve another mystery. Carl Gathmann has been accused of disturbing these graves, accused of being a spiteful white monopoly capitalist.

So, 30 fires have been set on his farm and the farm manager’s house petrol bombed. That manager has just told me what it took to get his wife and children out of the bath before the inferno engulfed their home. Now I am looking at a hole in the ground in the middle of a derelict field to try and determine if it is a disturbed grave or not.

A confession bubbles up that clears Gathmann of the allegation. What triggers it? ‘I am afraid they will snatch my life for admitting this,’ says the witness, ‘but I am more afraid…of God’s judgement if I do not tell the truth’.

Undisclosed Location

It is late at night before I find the township church where I have arranged to meet Charles Nxumalo. He is a man just shy of eighty, who, almost half a century earlier, was sent to the US where he received an excellent higher education on the Church’s dime. He shows me photos.

Among them are photos of his daughter’s wedding dress and the preparations that had been made for what was supposed to be the proudest day of his life as a father. But on the Sunday morning before her wedding, an impi came to burn it all down, including his home, and Nxumalo has lived in hiding ever since.

‘Do you want revenge?’ I ask.

‘Yes,’ he confesses, ‘but then I pray. It has been a long time and the prayers have put down my sinful yearnings. Two wrongs do not make a right. I want justice, fair justice, not revenge. The Bible teaches me that the vengeful trap themselves in sin. I see that everywhere in this country. Can you not see it? I must forgive, spiritually. On a practical level there must be justice through the law in a very specific way.’

Religion in South Africa

When I cannot sleep at night, I remember encounters like the ones mentioned above. There are good people who see through the political noise to perceive what matters, because they believe in a higher power. They are not just believers, they are doers.

They remind me of St Francis of Assissi’s line that his walking is his preaching, his actions his best example.

But to Ivo Vegter these Christians do not set an example that is consistent with the Bible, as he interprets it. He believes his is the only determinate reading of the text, according to which ‘(the) Bible condones slavery, including sex slavery, as well as actual human sacrifice’, along with rape, murder, and more evil deeds.

None of the Christians mentioned above believe that; they all interpret the Bible in a different way from Vegter, and I think it is safe to say that the overwhelming majority of Christians in South Africa interpret the Bible in hard contradiction to Vegter’s method.

Yet Vegter thinks that they should either abandon Christianity or interpret the Old Testament literally, as he does. He calls the third option ‘intedeterminism’, but it does not satisfy his preferred ‘epistemic basis’.

Science

He objects, because the ‘epistemic basis’ of religion is faith, not logic.

Vegter denies the basic observation that science’s background assumptions cannot be shown to be consistent (logically) or complete (logically). Vegter misunderstood my point in our last exchange, so I will move on to highlight the fact that logic itself requires an act of faith, according to the best logicians.

Lewis Carroll, arguably the greatest logician of the 19th century, showed that the fundamental operator of logic, modus ponens, is itself a matter of faith in the strict sense that it cannot be proved valid to someone who doubts it. Could Vegter prove Carroll wrong, or prove to the doubting Thomas that modus ponens is valid? I think not, but I’d be happy to see him try.

David Lewis, arguably the greatest modal logician of the 20th century, showed that there was no better argument, in the final analysis, against a radical sceptic than a simple shrug and the confession that all ‘knowledge’ comes within limits.

The ‘epistemic basis’ upon which all legible conversation rests is more tenuous than Vegter is willing or able to admit.

Morality and Ritual

Most people depend on their religion not for scientific analysis, but moral guidance. I would like to buttress those people, Christians in this instance, who interpret their faith in ways that do right when doing wrong is always so tempting. In fact, as I said at the start, people of faith have often buttressed me.

Vegter, by contrast, would rather Christians think the Bible condones rape and so destroy all Churches.

It is folly to think a faithless life is the best, or even possible, and I am certain Vegter would appreciate that if he interrogated his own beliefs. Epistemic humility is an option for some, but a must for those who put truth first.

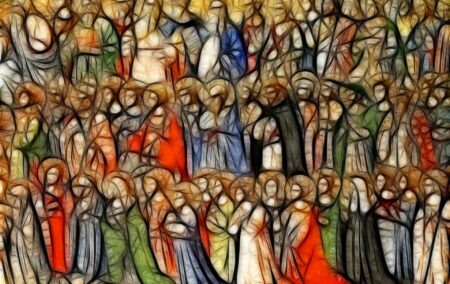

[Picture: Gerd Altmann from Pixabay]

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend