I recently watched Last Action Hero again. Released in 1993, it’s an Arnold Schwarzenegger action comedy that did indifferently in cinemas, but was a hit in the home media and movie channel market.

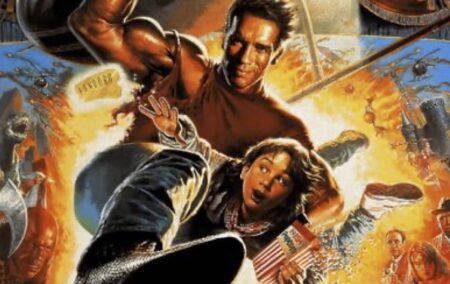

For those not familiar, it’s a wonderful spoof of the action movie genre. It follows the adventures of young Danny Madigan, an action movie fan who gets sucked into the fictional world of his hero, maverick detective Jack Slater, played by Schwarzenegger.

The film generates much of its impact from Danny’s interaction with the in-movie world: enough like reality to be recognisable, but far enough removed from it to be absurd. In a simulacrum of Los Angeles, much the same physical features exist, but they are co-opted to accommodate the over-the-top storyline. Entering the police station – passing iconic characters from Basic Instinct and Terminator 2 – Danny exclaims, ‘I was just in a real police station, and this is much nicer.’ He comments on the presence of an animated cat among the police officers (‘That cat is one of the best men I’ve got!’ responds the commander irritably). The LA of the film is populated by impossibly beautiful people, extreme fashions, its cityscape topped by clear skies and its life ordered by convenient coincidences so that things proceed without delay or interruption. Gunfights, explosions and the general mayhem of the storyline pass for the most part without undue consequence.

What reminded me of this movie was, oddly, the spate of attacks on the Institute of Race Relations over the past few months. Our critics have made a veritable blizzard of allegations against us. Some of these question the quality or reliability of our work; others take exception to the issues that we have raised. I disagree profoundly with these contentions, but within their own frame of reference they have a comprehensible logic. So, when one of our detractors remarked that he could not associate with an organisation that was in favour of civilian gun ownership, he was articulating a substantive policy and normative position. If this is a non-negotiable point of disagreement for him, then so be it (though the IRR has spoken in support of civilian gun ownership since at least 1997, so the objection seems to be some decades overdue).

Constant invocation

What has intrigued me is the constant invocation on the part of our critics of the politics of the United States. I count, since the first public attack on the Institute on 26 June, 15 pieces criticising us. Some were run on multiple platforms, considerably expanding their reach. Of these, all but one made some link to the US. That first attack, by Prof Roger Southall (I can, incidentally, recommend his book Liberation Movements in Power: Party and State in Southern Africa), had this to say:

In recent weeks [the IRR] has opted to stoke SA’s culture wars, launching attacks upon critical race theory and defending, and I quote, ‘the gun-owning rights of law-abiding citizens’. What Donald Trump did yesterday, apparently, the IRR will do tomorrow. What’s next: advocating the restriction of voting rights?

He is correct in identifying our position on Critical Race Theory (we are opposed to it) and on civilian firearm ownership (supportive, subject to a strict set of controls). What this has to do with Donald Trump is somewhat unclear. Is the implication that we are following Trump’s lead? Or that our positions are similar to those of Trump, and thus ipso facto bad?

I’d suggest the latter. I don’t think his argument is accurate, since if I had to identify the seminal ‘Trumpist’ issue it would be hostility to immigration – we at the IRR have generally been quite favourably disposed to immigration, and have written in defence of the rights and contribution of immigrants at least since the 1990s. I’ve done so. As for ‘voter suppression’, we have been very vocal in wanting to ensure that elections proceed on schedule precisely to ensure that South Africa’s people have the right to their democratic expression. (I’d say that if there has been a case of voter suppression in South Africa since 1994, it would have been the 1999 Constitutional Court decision disallowing all but bar-coded ID documents for the election of that year.)

Seamless connection

Subsequent writers picked up these themes, drawing what seems like a seamless connection between ourselves and our positions and malign, right-wing influencers in the US. Said one contribution:

The IRR has adopted the notions of economic and individual freedoms of libertarian groups in the US, which advocate the removal of the state from regulating the economy and society.

Remarked another:

It’s especially difficult to figure out why the IRR would eschew the promotion of good race relations in favour of entering the anti-critical race theory debate, which is heading to be a key campaign platform of far-right racists in the 2022 US elections. This used to be the SAIRR, focused on improving the lot of South Africans. Why has this focus changed?

An extensive piece in the Daily Maverick commented:

An objection the think-tank has increasingly faced in recent years is that the Institute appears to be taking on the concerns and values of the American right wing: from opposing gun control to slamming Black Lives Matter and Critical Race Theory, both of which have been the subjects of SAIRR reports over the past year.

Another Daily Maverick commentator, in a somewhat more thoughtful piece, nevertheless wrote that some of the issues the IRR is tackling – such as CRT – ‘seem largely unrelated to issues central to South African life and issues’. His advice was to focus on South African issues and to ‘move away from any of those fevered preoccupations of US right-wing propagandists and polemicists’.

But what took the proverbial biscuit was a letter to the Business Day by one Jean Redelinghuys:

The proposition that the Institute of Race Relations occupies a ‘sensible middle’ ground is not only ludicrous in view of past fellow travellers in the SA political landscape, but just imagine if the IRR registered as a political party in the US. Where would the US media place it?

Homegrown issue

But these issues are germane to South Africa. Our stance on firearm ownership owes very little to the US, but very much to the Firearms Control Amendment Act (to be fair, at least one attack acknowledged this, though others did not). I have argued – reasonably, I think – that this is a bad piece of legislation, with implications not only for self-protection, but also for sporting and the preservation of heritage. The politics of firearm ownership has been an issue in South Africa, quite independent of any American stimulus, since the 19th Century. It’s a homegrown issue.

On CRT, I have argued here and here, that it has made landfall in South Africa, both under its own name and under various other descriptions. Its foundational concepts are well entrenched in South Africa – and this was the case long before the notion of CRT was widely recognised. The preoccupation with demographic representivity is one such example. Indeed, CRT-style reasoning, and the appeal to thinkers associated with the CRT canon, was on display two decades ago, at the 2001 National Conference on Racism – these were ideas drawn on and endorsed largely by what one might loosely call South Africa’s ‘progressive’ intellectuals and activists. (Who, then, should we say, was really responsible for introducing this stuff to South Africa’s public conversation?) We voiced our concerns about these ideas at that time.

But why the fixation on the supposed American connection?

In some ways, it is a natural extension of the cultural reach of the US. True enough, the US has vast real-world influence on people’s lives across the world. It can be of great importance who assumes its presidency, for example, or how he or she determines to use American power. It makes eminent sense to be informed of the state of America, and to acknowledge that what takes place there can reverberate here. But I sense that something more is at play.

Virtual world

Many of us experience parts of our lives rather like Danny Madigan did after he was pulled into Jack Slater’s world. We live in our own day-to-day existences, but also wander in and out of a virtual world that is crafted with the US in mind. It’s in the news we watch, the entertainment we consume, the fashions and fads we adopt. Those with my years might remember the numerous American accents in television adverts (or should that be ‘commercials’?) in the 1980s, despite South Africa’s relative isolation at the time.

This is not a uniquely South African phenomenon. (I once read an account of a panicked child in the UK who dialed 911 for help – unaware that the British equivalent was 999.) The rather controversial American author and filmmaker, Dinesh d’Souza, wrote in a book entitled What’s so Great about America:

Drop in at a hotel in Buenos Aires or Bombay, and the bellhop is whistling the theme song from Titanic. Take a train through a village in Africa or the Middle East, and you will see a young boy, seemingly untouched by Western civilisation. When you look closer, however, you see that he is wearing an Orioles baseball cap. Moreover, he has the cap worn back-to-front, to show the adjusto-strap to advantage. The boy also has a sauntering walk that seems uncharacteristic and vaguely familiar. Then it hits you; that little fellow wants to be Chris Rock! He wants to be an American!

Perhaps d’Souza overstates his case, but it illustrates (as he later states) that very many people around the world are ‘magnetically attracted’ to America. America is probably alone in the world in being its own ideology – not just having an official ideology, but in its existence supposedly embodying a set of ideals. It has variously been called the ‘last best hope of earth’ and ‘a shining city on a hill’. America has been a force, a destination and an ideal.

‘Losing their heritage’

Great influence comes with great resentment. There is certainly no shortage of this in South Africa. Speaking as premier of the Western Cape on Heritage Day in 2007, Ebrahim Rasool turned d’Souza’s words on their head as he complained:

Our children are losing their heritage; they are the victims of MTV and of Hollywood. They are the victims of single forms of music, they are the victims of single forms of genres and we need you to remind us that our richness cannot be sacrificed on the altar of Hollywood or MTV. We have our own music, we have our own drama, we have our own poetry and we have our own art. We cannot Americanise the whole world. We cannot make the whole world uniform. We are losing our heritage and our children are becoming more Americanised rather than being proud Africans. We must push back the American way of making culture uniform across the world, making it the common denominator amongst all people.

I would suggest that in political terms, being an ‘African’ is a rather contested idea, and some of its leading exponents would not necessarily concede its availability to all South Africans, least of all in a province with the demographic profile of the Western Cape – but you get the point.

And I think that something has taken place over the past two decades that has pushed the US into people’s consciousness to a degree that exceeds anything that went before. Partly, this is geopolitical – the 9/11 attacks, the intervention in Afghanistan, and the much more controversial invasion of Iraq.

Increasing polarisation

Much can also be attributed to the influence of up-to-the minute media coverage of the country that outsiders have access to. Add to this the increasing polarisation of media coverage in the US, and the fact that it is no longer only in text, but in ever-present video footage, and Danny Madigan’s experience becomes our own. We feel a powerful attachment not just to events, but to the various factions involved in them. What happens in the US is taken as deeply personal, something probably enhanced by disappointment and frustration at the state of our own country… a symptom of low national self-esteem?

I don’t think it would be an exaggeration to say that it’s as easy to get news on the goings-on in St Louis or San Diego as it is to get news from Standerton. Quite probably much easier.

And then, of course, there is Trump.

Trump seems to have triggered just about every emotional and moral tripwire among progressives the world over. There’s a lot going on there to be sure: ideology, policy, character… Perhaps as an extension of the presence of America in our consciousness, Trump became a dreadful and imminent shadow, a Rorschach test of immorality or an avatar of all that is sinister and evil.

From this point of view, to be seen as a Trumpist in some way is to be morally decrepit. Speaking personally, I am very restrained in expressing views on foreign politics – particularly the domestic politics of faraway places – recognising the limits of my own expertise. Yet since Trump’s election, and particularly in 2020, I was repeatedly assailed with demands from acquaintances that I ‘speak out’. (They clearly overestimate the influence of my Facebook page, and the three or four people who ever comment on it.) These were people who had shown (and show) scant interest in my work on property rights, or on African governance, or on East Asia – where I do feel I have something constructive to add. It was a revealing experience.

Met with disapproval

In a few private conversations I have had on the matter, even an attempt to understand the Trumpist perspective has been met with disapproval. (For what it’s worth, I found the take on Trump’s appeal that was built around JD Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy to be intriguing and convincing.) Condemnation without qualification as a moral imperative seems to be the requirement. I couldn’t help thinking that what was playing out mirrors the views of the late French filmmaker Claude Lanzmann that it was obscene even to try to understand Hitler and the Holocaust. These emotions run deep.

Maybe all of this explains why South Africans – right up to the incumbents in the Union Buildings – failed to take much of an interest in the killings of people by our security forces enforcing South Africa’s lockdown last year, but responded with enormous energy when a police officer killed George Floyd in Minneapolis. It was conveyed as all that was twisted and vile about Trump’s America (or America generally?), and a world-historical struggle to which so many seem to feel a connection – more so, at any rate, than the workaday brutality and contempt for life that all too often characterises South Africa. As Gareth van Onselen, formerly of the IRR, commented: ‘The death of Collins Khosa and others only became a cause célèbre because of what is happening in the US, the land from which we take our social justice cues.’

The mass incarceration of Uighurs by the Chinese state, meanwhile, is of peripheral interest.

I find this concerning. It is a reductio ad Trumpium, implying that there can be no reasonable debate about these matters. Maybe I’m missing some sort of nuance, but I don’t think so.

Jean Redelinghuys’s letter is explicable in this context, though no less ridiculous for it. Why on earth a (presumably) South African reader of a South African publication would propose that an organisation based in and operating in South Africa should be measured by the US media for its positioning in US politics makes no rational sense at all. It’s as absurd and out of place as the cartoon cat that Danny Madigan noticed in the fictional police station.

Sense of proportion

None of this is to say that what goes on in the US is irrelevant or that South Africans should ignore it. I am glad that South Africans are able at times to escape their parochialism. But I think that we would do well to try for a sense of proportion. American phenomena do have a way of travelling; they may be positive or negative, and we all have a right and duty to interrogate them. That is exactly what we at the IRR have been engaged in regarding CRT. If this is an obsession for ‘US right-wing propagandists and polemicists’ or Fox News (interesting how we instinctively understand the cultural signifier in that name), well, that’s their issue. We have come to recognise its dangers in South Africa for reasons that have little to do with the US’s circumstances, and everything to do with our own. Our focus is on the intrusion of race-based thinking in Johannesburg, not Virginia. We are quite open to being critiqued on that basis.

And invoking Donald Trump is less an argument than a smear, and not a very intelligent one. It’s not a game-winning trump card (pun sort of intentional). I’m sure we can all do better.

What I’m suggesting is that sometimes we all might do well to check ourselves in how we receive and process our interaction with American phenomena, and the assumptions we make about them, progressives no less than anyone else. America’s influence is large, yes, and its experiences offer useful and not-so-useful lessons; but its influence is not necessarily determinative. We outsiders need to try and understand it on its own terms, and be reflective in understanding how it manifests itself in our own lives. I’m reminded of Frederik Van Zyl Slabbert’s comment in the 1980s that ‘we here in South Africa have problems to solve for which the rest of the world has found no solutions. That in itself is a great challenge.’ It reminds one that as much as the outside world intrudes into South Africa – in reality or in the imagination – and as much as we may draw on influences from abroad, ultimately the resolution of our problems will only be found here.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend