With heavy lockdown receding into the past there will need to be a frank evaluation of whether it worked. It may be possible to make a serious case that our lockdown delayed the spread of Covid-19, though I have not seen any such argument in South Africa.

For those who take ‘the lockdown worked’ to be an article of faith, here are the 10 cold facts to reckon with.

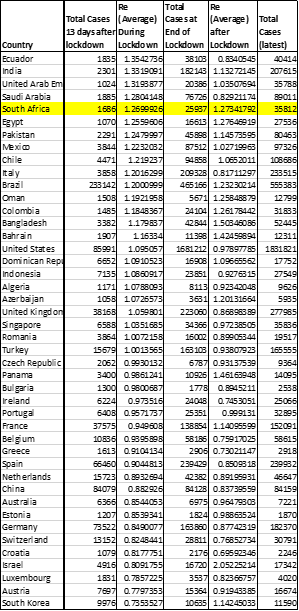

1 – South Africa had one of the world’s least effective lockdowns

Our lockdown was one of the least effective at reducing the effective reproduction rate, Re, of Covid-19. Of countries that had 1 000 confirmed cases by the second week of lockdown, only Ecuador, Saudi Arabia and India did worse than South Africa.

In Ecuador and Saudi Arabia, Re subsequently came down below 1, meaning no more exponential growth. The UAE failed at that, but our average Re post-lockdown remains higher than theirs, too.

South Africans are a proud people, so this will be a difficult pill to swallow – there is a strong case that we had the least effective lockdown on the planet.

Source Oxford’s OurWorldInData and own Re calculations. Note, ‘Re average during lockdown’ calculations begin from third week of lockdown, at which point lockdown is expected to have predominant effect. ‘Lockdown’ is measured as stay-at-home orders, ‘required (few exceptions)’, as per OurWorldInData.

2 – There was an alternative to lockdown

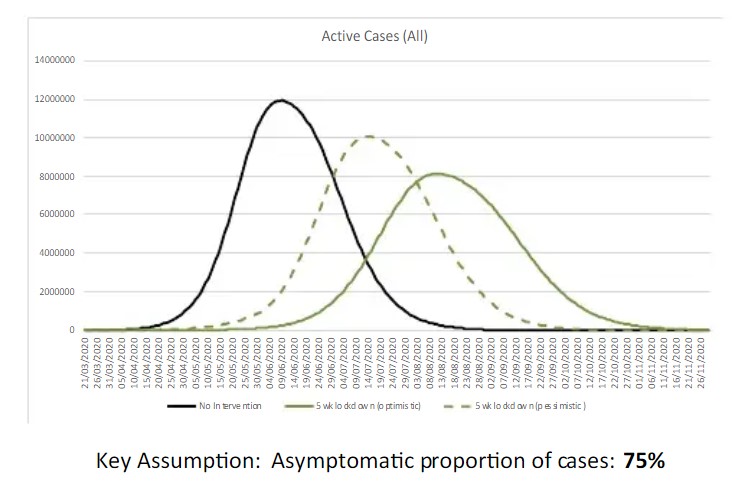

The government has repeatedly given graphs to show that even if lockdown did not make the curve flat, it did flatten the curve compared to what it might otherwise have been. The following graph is from the government advisors’ official report.

Long-term projections: impact of lockdown

It is on this basis that President Ramaphosa repeatedly said the lockdown served its purpose, to ‘delay the spread of the virus’. Bad as things are, without the lockdown they are supposed to have been worse.

But the ‘no intervention’ scenarios in all published South African cases follow the notorious Neil Ferguson ‘do nothing’ model in which no ‘spontaneous changes in individual behaviour’ occur. In such models there is zero voluntary masking, zero new hand-washing or social distancing, and even sick people continuing to go to work and responding to the phrase ‘you’re spreading Covid’ with a blank stare.

The lockdown was undoubtedly more effective than that at delaying the spread of Covid-19. But, as we used to say in high school, that is just putting the bar on the ground, stepping over and calling yourself a high jumper.

The true alternative is not ‘do nothing’ but ‘Call Up’. In a Call Up scenario, governments enforce only light regulations – like school closures and/or border controls and/or quarantine of the sick and their contacts and/or aggressive testing, while boosting public health. But, in Call Up, most adults are left to make decisions for themselves to delay Covid-19’s spread.

South Africa was in a Call Up scenario from March 15 until the lockdown on March 27. The country has largely reentered a Call Up scenario, at least since June 1. There is great hope that this will ‘delay the spread’. These immediate and obvious facts make it very difficult to ignore the reality and efficacy of our own Call Up in contrast to lockdown, but under the advice of ‘science’ Ramaphosa has ignored his own Thuma Mina Call Up nevertheless, by averring that the only alternative to lockdown is ‘do nothing’.

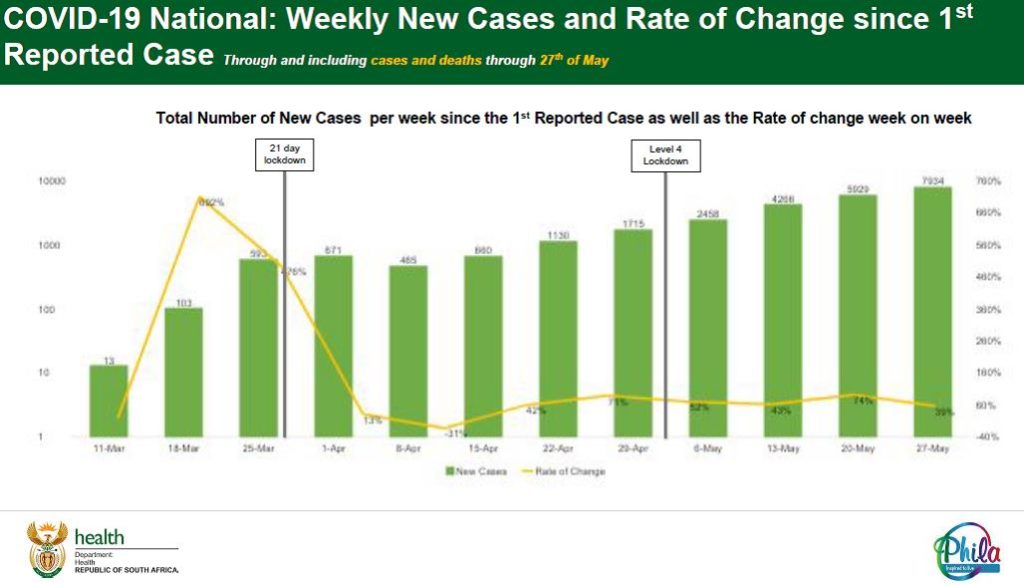

3 – Official data show our ‘call up’ beat our lockdown

The above graph comes directly from the Department of Health, so forgive it for being a bit hazy. The yellow line shows the rate of new cases spiking at March 16 and then dipping precipitously, before the lockdown.

Other graphs indicate that South Africa reversed the spread of Covid-19 from March 26, the last day of Call Up. Dr Salim Karim, top epidemiologist and chairperson of the Ministerial Advisory Committee, said, based on this, that ‘our epidemic trajectory is unique’.

Karim had three theories about why our curve flattened dramatically before lockdown could possibly have had any effect. The first and second were that the testing was faulty, and the third was that lockdown worked, magically, immediately, or even before it began.

Dr Karim demonstrably failed to consider the fourth theory, namely that the Call Up was en route to curbing Covid-19 in South Africa. Dr Max Price apparently makes the same mistake. Again, some ‘science’ following Ferguson, has treated South Africans like mindless ants who ‘do nothing’ to change their behaviour unless the heavy boot of the army crushes us into shape.

4 – Long lockdowns are worse in poor countries

Poor countries cannot afford to supplement incomes like rich ones during lockdown. The United Kingdom and United States both budgeted for fiscal stimulus amounts of more than $6 000 per person. South Africa could only budget for $40 per person.

In poor countries, more people will be able to socially distance, mask and maintain hygiene at work than at home. That is true when work sites offer more space, better sanitation, and food facilities.

In poor countries, extended lockdowns produce dire hunger, motivating people to seek an income in less secure ways than formal employment offers. In poor countries that require grants to be collected in person rather than transferred digitally, this problem is compounded. South Africa is just such a poor country.

And, finally, in poor countries the limitations on resources mean that lockdowns suck up precious energy that could be used to make Call Ups work. If all the effort that went into radically transforming South Africa into a de facto prison had been used to ramp up testing, and to support our transport system to get taxis and buses to work at 50% capacity instead, we would arguably have had a lower Re.

5 – Our lockdown was an unconstitutional power grab

There is the Gauteng High Court’s ruling – the government is appealing the judgment – that at least some of the lockdown regulations were invalid and unconstitutional. In addition, the issuing of business certificates to operate was found ‘unlawful’.

But arguably the most fundamental concern is that parliamentary oversight was effectively abrogated for months. In violation of the constitution, power has been grabbed, and taken into the hands of a few irrational regulators.

6 – The lesson from Vietnam

Knowing that lockdowns are harder on poor countries, but appreciating that they are temporarily necessary to ‘buy time’, Vietnam implemented hard lockdown for only three weeks, and, even then, ‘never had a total national lockdown, but swooped in on emerging clusters’. For the rest, Vietnam relied on a heavy Call Up strategy.

Vietnam’s GDP is expected to grow in 2020, and it has no recorded Covid-19 deaths.

7 – Without the long lockdown, South Africans would be wearing the national flag on their masks

Masks imprinted with the South African flag have long been available; I saw a few of them proudly worn during the Call Up (pre-lockdown) in provincial dorps and townships. Since then, however, I have not seen any such masks at all.

We South Africans love our flag. You could see that when it adorned the side-mirrors of millions of cars during the 2010 World Cup, among other occasions. Wearing the flag on our masks would signal a patriotic sense of duty in masking, as a way to protect fellow South Africans and our healthcare system. That this has not happened is emblematic of the lockdown having turned the general conception of us against the virus to one in which most people oppose both the virus and government lockdown. Opinion polls strongly support this view.

8 – Government’s response has been more Eurocentric than politicians will admit

This problem has two sides. The first is border control. In a Call Up, voluntarism is heavily emphasized, but the mistake is never made to think that government regulation does not also have a role to play. From January through mid-March, the big debate in Europe and the US was whether or not to ban travel from high-risk zones.

The World Health Organisation and China argued for domestic lockdowns, while keeping international borders open, an argument reinforced by those from even the most unlikely corners who said shutting borders was ‘racist‘. This view was deranged.

The following countries issued travel bans from high-risk zones early on: Taiwan and Singapore, January 23; Vietnam and Japan, February 1; South Korea, February 4; and Indonesia, February 5.

South Africa, by contrast, banned travel from high-risk zones only on March 18, in line with countries like Germany, Sweden, and Canada. At that point, majority-white countries could be considered high-risk too (Spain and Italy) so there was no longer a concern about ‘racism’ against Asians.

That might have satisfied some social identity estimators, but it did nothing to respect the judgments of actual Asian countries, or to stop the early import of Covid-19 into vulnerable, poor South Africa.

Second, the only Call Up model generally considered domestically was Sweden’s. Sweden’s border problems were compounded by its old population and poor testing. Despite all this, Sweden has flattened the curve through Call Up, which our lockdown failed to do. While diversity was considered in European responses (Sweden versus the rest), no diversity has been recognised by leadership in Asia.

The ‘Chinese model’ came to represent all of Asia. This, even though Taiwan, part of China, did a better job of stopping Covid-19 without any lockdown of work or stay-at-home orders whatsoever. Japan has an exemplary record without any lockdown either. South Korea (rich) and Vietnam (poor) have only had stay-at-home restrictions for 28 and 21 days respectively. Thailand never instituted a stay-at-home lockdown, and neither did Malaysia. Mongolia had what we call ‘Level 5’ lockdown for just three days.

By ignoring all of Asia except Beijing, we overlooked both the best Call Up paragons and the option to try and intersperse our own Thuma Mina Call Up with a much shorter and more limited lockdown. Who in government will ever admit that a fixation on majority-white countries deranged our judgement on the question of closing borders, and the broader approach too?

9 – Anyone who really ‘cares for the poor’ will be open to adjusting their judgements based on evidence

There are two ways to show you care. One is to say it over and again, very loudly. The other is to consider the facts, weigh up costs and benefits, take in new evidence as it comes along, and judge accordingly what is best to do.

Critics of the South African lockdown (like myself) had better follow the evidence-based model, preparing to alter positions based on new evidence.

But lockdown zealots who see any doubt of the lockdown as proof that the doubters just ‘want people to die’ will not care about what really worked and what the best alternatives were. All that matters to these ‘champions of the poor’ is how loudly and proudly they celebrate the heavy boot that came down on this nation, as if we were mindless ants.

10 – Lockdown had another goal: wealth destruction

Julius Malema said, ‘let us rather die with our boots on than dying protecting the white monopoly economy’, as part of his call for the ‘white economy‘ to fall. Head of the National Coronavirus Command Council Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma said: ‘Covid-19 also offers us an opportunity to accelerate the implementation of some long agreed-upon structural changes…These opportunities call for more sacrifices and if need be… “class suicide”.’

President Ramaphosa said Covid-19 has not ‘negatively affected’ the ‘restructuring of the economy’. ‘If anything Covid-19 now gives a much stronger platform’ to ‘transform and restructure’ the ‘colonial and racist’ economy. (This, an economy that has made so many in the ANC rich.)

Is the loss of up to 1.8 million jobs a goal for the National Democratic Revolution, or is it an own-goal wrecking the lives of millions?

Perhaps massive wealth destruction does ‘strengthen the rationale’ for ‘long agreed-upon’ calls for National Democratic Revolution through Expropriation without Compensation, looting pensions, nationalising the Reserve Bank, and the everlasting expansion of the patronage network.

If the goal is to effect ‘radical economic transformation’ in a Venezuelan fashion of ‘21st century socialism’, which turned the richest country in the region into the poorest, then following one of the world’s longest, most brutal, and least effective lockdowns with the ‘long agreed-upon’ policy moves listed above will surely ‘serve the purpose’.

If Ramaphosa meant what he said when he called the dictator of Venezuela ‘my Brother’, then perhaps the lockdown served its true purpose after all – not to save South Africa from Covid-19, poverty and death, but rather to ‘save’ us from life, liberty and the pursuit of individual meaning.

[Picture: Drew Beamer]

If you like what you have just read, subscribe to the Daily Friend